| Research Article | ||

Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(8): 3759-3769 Open Veterinary Journal, (2025), Vol. 15(8): 3759-3769 Research Article In silico evaluation of vitamin D3 as a dual inhibitor of CDK2 and Bcl-2 in colorectal cancerJauharotus Shobahah1,2, Sri Puji Astuti Wahyuningsih3*, Dwi Winarni3, Mochammad Aqilah Herdiansyah3 and M Ainun Najib Aly41Doctoral Program of Mathematics and Natural Sciences, Faculty of Science and Technology, Universitas Airlangga, Surabaya, Indonesia 2Department of Biotechnology, Faculty of Food Security, Universitas Negeri Surabaya, Surabaya, Indonesia 3Department of Biology, Faculty of Science and Technology, Universitas Airlangga, Surabaya, Indonesia 4Faculty of Pharmacy, Universitas Airlangga, Surabaya, Indonesia *Corresponding Author: Sri Puji Astuti Wahyuningsih. Department of Biology, Faculty of Science and Technology, Universitas Airlangga, Surabaya, Indonesia. Email: sri-p-a-w [at] fst.unair.ac.id Submitted: 19/06/2025 Revised: 22/07/2025 Accepted: 27/07/2025 Published: 31/08/2025 © 2025 Open Veterinary Journal

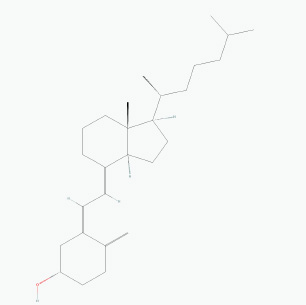

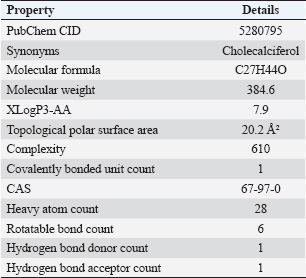

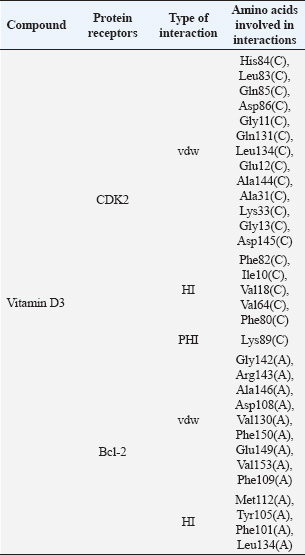

ABSTRACTBackground: The potential anticancer properties of vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol) have garnered growing interest. Epidemiological and preclinical studies suggest an inverse correlation between vitamin D3 levels and CRC incidence. However, the precise molecular mechanisms and direct targets through which vitamin D3 exerts anticancer effects remain inadequately characterized. Aim: This study aimed to investigate the dual-targeting potential of vitamin D3 against two key oncogenic proteins involved in the pathogenesis of CRC: cyclin-dependent kinase 2 (CDK2), a critical regulator of cell cycle progression, and B-cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2), an anti-apoptotic protein implicated in tumor survival. Method: Molecular docking was performed to assess the binding affinity of vitamin D3 to CDK2 and Bcl-2. Molecular dynamics simulations were used to evaluate the stability of the docked complexes over time. Absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity (ADMET) analysis was performed to predict the pharmacokinetics and safety profile of vitamin D3. Results: Docking analysis revealed strong binding affinities of vitamin D3 to both CDK2 (−9.5 kcal/mol) and Bcl-2 (−8.2 kcal/mol), suggesting stable interactions at the ATP-binding site of CDK2 and the BH3-binding groove of Bcl-2. Molecular dynamics simulations confirmed the conformational stability and sustained interactions of vitamin D3 with both targets throughout the simulation period. ADMET predictions indicated favorable oral bioavailability, low toxicity, and acceptable absorption and distribution characteristics, although solubility and plasma protein binding were limited. Conclusion: This study provides the first computational evidence that vitamin D3 may exert anticancer effects in CRC via dual mechanisms—cell cycle arrest through CDK2 inhibition and apoptosis induction through Bcl-2 modulation. These findings offer a novel perspective on the therapeutic repositioning of vitamin D3 as a multi-target agent in CRC management and warrant further validation through in vitro and in vivo studies. Keywords: Bcl-2, CDK2, Colorectal cancer, Molecular docking, vitamin D3. IntroductionAs one of the leading causes of cancer-related deaths worldwide, colorectal cancer (CRC) continues to pose a serious public health risk (Roshandel et al., 2024). Disruptions in a number of vital cellular processes, especially those controlling cell division and programmed cell death (apoptosis), are closely linked to the development of CRC. B-cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2) and cyclin-dependent kinase 2 (CDK2) are two important proteins implicated in these processes (Yasmeen et al., 2003; Weiswald et al., 2017). CDK2 is crucial for regulating the cell cycle, especially during the transition from the G1 to the S phase. Uncontrolled cellular growth in a number of cancers, including CRC, has been linked to its dysregulation (Tadesse et al., 2020). However, Bcl-2 is a key anti-apoptotic factor that helps cancer cells avoid dying. Elevated Bcl-2 expression is frequently linked to treatment resistance and worse clinical outcomes in CRC (Tukaram Patil et al., 2019; Alam et al., 2021). Vitamin D3 was originally identified as a calcium metabolism regulator and is now known to exert pleiotropic effects on cell division, proliferation, and apoptosis (Samuel and Sitrin, 2008; Wang et al., 2024). Several epidemiological studies have linked elevated serum vitamin D3 levels to a lower risk of CRC (Zhou et al., 2021). Moreover, vitamin D3 has demonstrated the ability to influence the expression and function of essential cancer-related proteins. Nevertheless, most current research emphasizes indirect mechanisms, such as transcriptional regulation and intracellular signaling network modulation (Varghese et al., 2020; Blasiak et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2024). To date, no published studies have explicitly examined the effect of vitamin D3 on CDK2 expression or activity in CRC, indicating a gap in the literature that this study aims to address through computational modeling. Despite the established roles of CDK2 and Bcl-2 in the progression of CRC, the possibility that vitamin D3 could directly bind and inhibit both proteins has not been adequately explored. Furthermore, no experimental or computational study has investigated the dual-targeting potential of vitamin D3 against these two oncogenic drivers. Considering that CDK2 and Bcl-2 regulate distinct yet complementary cancer hallmarks—cell cycle dysregulation and apoptosis evasion—their simultaneous inhibition could yield synergistic therapeutic effects. Vitamin D3 is an attractive candidate for such dual-target therapy given its multifaceted biological activity, favorable safety profile, and potential for drug repositioning. Therefore, this study employs an integrated in silico approach—encompassing molecular docking, molecular dynamics simulation, and absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity (ADMET) profiling—to evaluate the direct interactions of vitamin D3 with CDK2 and Bcl-2 and assess its potential as a novel multi-target therapeutic agent in CRC. Materials and MethodsMolecular docking and ligand preparationThe two-dimensional (2D) chemical structure of vitamin D was illustrated using ChemDraw version 18 (PerkinElmer Informatics Inc., Shelton, WA, USA) and subsequently converted into a three-dimensional (3D) conformation using Chem3D version 18. The canonical SMILES notation for further analysis was retrieved from the PubChem database (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). Crystal structures of CDK2 in complex with AZD5438 (PDB ID: 6GUE) and Bcl-2 bound to Navitoclax (PDB ID: 4LXD) were acquired from the RCSB Protein Data Bank (https://www.rcsb.org/). All co-crystallized ligands and water molecules were detached utilizing BIOVIA Discovery Studio 2019 (Dassault Systèmes BIOVIA, San Diego, CA, USA). The receptor structures were prepared for docking, and their binding sites were identified based on the original ligand positions. Three known inhibitors were used as reference ligands to benchmark the docking performance: AZD5438 (for CDK2), Navitoclax (for Bcl-2), and Quercetin (for both CDK2 and Bcl-2). These compounds were included to allow direct comparison of binding affinities with vitamin D. Docking simulations were performed using PyRx version 0.8 (SourceForge, San Diego, CA, USA) with AutoDock Vina as the docking engine. Each ligand was docked into the active site of its corresponding receptor, and the binding affinity (expressed in kcal/mol) was recorded. More negative binding energy values indicate stronger binding between the ligand and target protein (Alifiansyah et al., 2024; Herdiansyah et al., 2024). The pharmacokinetic properties of vitamin D, including its drug-likeness based on Lipinski’s Rule of Five, were evaluated using the SCFBio web server (http://www.scfbio-iitd.res.in/software/drugdesign/LIP1.jsp). Molecular dynamics simulationTo assess the structural dynamics of the ligand–protein complexes, molecular dynamics simulations were performed using the CABS-flex 3.0 web server (https://lcbio.pl/cabsflex3/). This coarse-grained simulation platform generates an ensemble of protein conformations that reflect flexibility and conformational changes over time. The resulting models were analyzed to extract the root mean square fluctuation (RMSF) and radius of gyration (Rg) values directly from the simulation output. In addition, root mean square deviation (RMSD) values were calculated manually by aligning the ensemble of PDB models to the initial structure using PyMOL, with each model superimposed onto the first frame to identify backbone deviations throughout the trajectory. These parameters collectively provided insight into the conformational flexibility, compactness, and structural stability of each complex during simulation. ADMET parameter analysisADMETlab 2.0, an in silico tool that predicts ADMET qualities based on molecular structure, was used to assess the pharmacokinetic and toxicological profile of vitamin D3. The platform assessed 26 vitamin D3 SMILES factors across five major ADMET categories. These metrics were used to assess the drug-likeness of the compound and its systemic CRC treatment potential. Ethical approvalNot needed for this study. ResultsThis new study examined the binding affinity of vitamin D3 with various proteins associated with CRC onset. The attributes of vitamin D3, derived from PubChem, along with its chemical structure illustration (Fig. 1), are detailed in Table 1. The molecular docking of vitamin D3 (Table 2) revealed strong binding affinities to both CDK2 (−9.5 kcal/mol) and Bcl-2 (−8.2 kcal/mol). To contextualize these values, three known inhibitors were employed as reference compounds: AZD5438 for CDK2, Navitoclax for Bcl-2, and quercetin as a natural comparator with established anticancer activity. A docking value of −9.0 kcal/mol was shown by AZD5438 with CDK2, and the greatest interaction with Bcl-2 was shown by Navitoclax at −10.7 kcal/mol. Quercetin demonstrated moderate binding to both targets, with scores of −9.0 kcal/mol for CDK2 and −7.5 kcal/mol for Bcl-2. These comparisons place vitamin D3 above both AZD5438 and quercetin in terms of affinity toward CDK2 and between quercetin and Navitoclax in terms of its interaction with Bcl-2.

Fig. 1. Chemical structure of vitamin D. Table 1. The characteristics of vitamin D3.

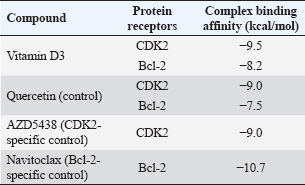

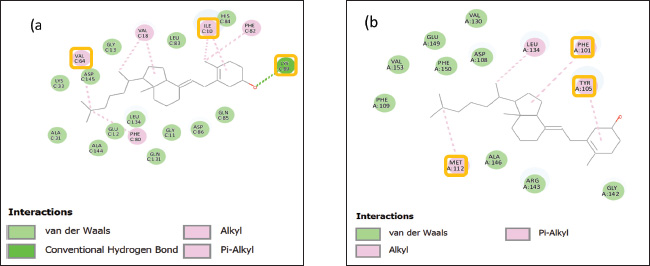

Moreover, molecular docking revealed that vitamin D3 interacted with residues located in the functional regions of both target proteins (Table 3). Vitamin D3 formed a hydrogen bond with Lys89 in the CDK2 complex and engaged in hydrophobic interactions with residues such as Val64 and Ile10, situated within the ATP-binding site (Fig. 2A). Additional interactions included van der Waals forces with residues such as His84, Leu83, and Gln85. Vitamin D3 interacted with residues in the BH3-binding groove in the Bcl-2 complex, forming hydrogen bonds with Met112, Tyr105, and Phe101 (Fig. 2B). Several van der Waals interactions were observed with residues such as Gly142, Val130, and Glu149. These interactions are presented in Table 3. Table 2. Molecular docking-based binding affinity (kcal/mol) of vitamin D3 and known inhibitors against CDK2 and Bcl-2 for benchmarking purposes.

Table 3. Amino acid residues and interaction types involved in CDK2 and Bcl-2 as predicted by molecular docking.

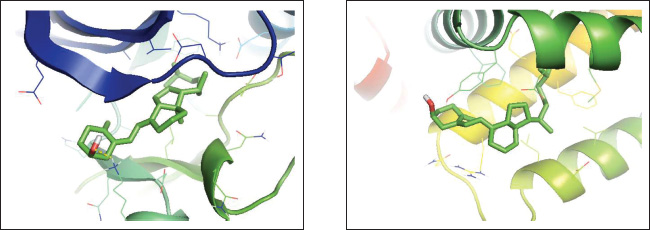

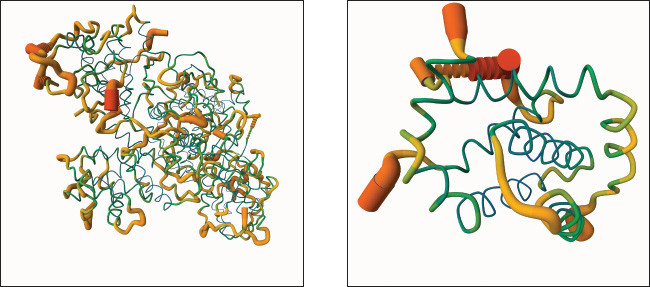

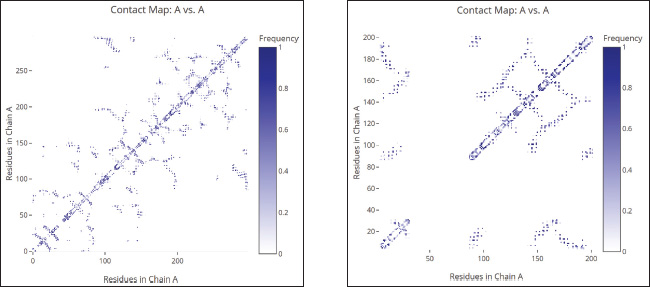

Figure 3A displays the 3D binding interaction between vitamin D and CDK2, indicating that the ligand is positioned within the active pocket of the protein and surrounded by secondary structural elements such as α-helices and β-sheets. The ligand adopts an extended conformation and closely interacts with nearby residues. Figure 3B shows the vitamin D docking position within the Bcl-2 binding cavity, which is located in a predominantly hydrophobic region formed by surrounding α-helices. The steroidal vitamin D scaffold aligns tightly with the binding groove and is enclosed by nonpolar residues, suggesting spatial accommodation within the Bcl-2 pocket. The molecular dynamics (MD) models of CDK2 and Bcl-2 proteins obtained from CABS-flex 3.0 are presented in Figure 4A and B, respectively, highlighting their structural behavior throughout the simulation. As shown in Figure 4A, the CDK2 protein exhibits considerable conformational flexibility, especially in the loop regions, while the α-helices and β-sheets maintain relative structural stability. The green backbone indicates the initial configuration, and the orange segments reflect the time-dependent deviations. Similarly, Figure 4B shows the MD model of Bcl-2, where the overall structure remains compact with localized fluctuations, particularly in the loop and terminal regions. Structural changes in Bcl-2 are less pronounced compared to CDK2, indicating a more rigid conformation during the simulation. These visualizations confirm the dynamic nature of both targets, with CDK2 displaying higher structural adaptability, which could influence ligand interaction and binding site accessibility.

Fig. 2. Two-dimensional visualization of the interaction of the receptor–compound complex. (A) CDK2. (B) Bcl-2. Yellow-outlined residues (e.g., Val64, Ile10, Lys89 in Fig. a; Met112, Phe101, Tyr105 in Fig. b): These are critical residues within the binding pocket that play essential roles in ligand recognition, binding affinity, and selectivity.

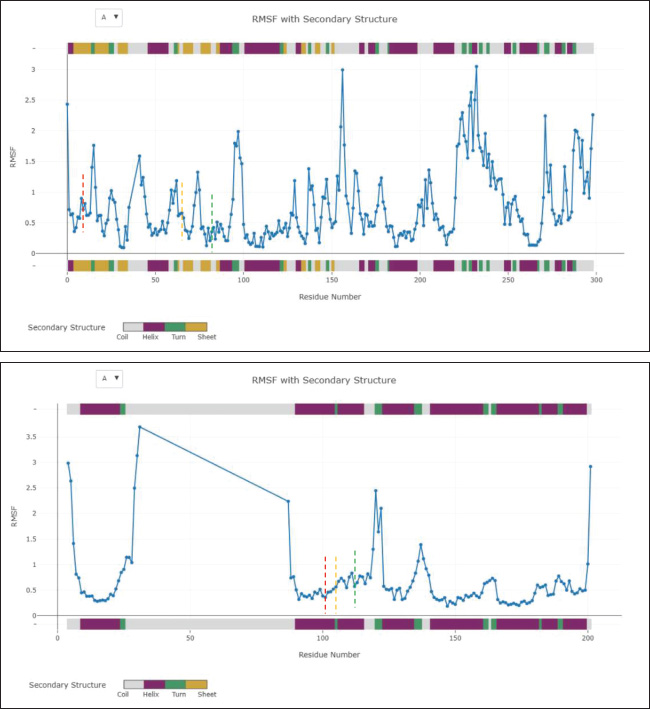

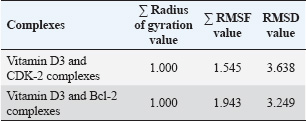

Fig. 3. Three-dimensional molecular interaction binding of protein interacted with vitamin D3. (A) CDK2. (B) Bcl-2. Furthermore, MD simulations demonstrated that both CDK2–vitamin D3 and Bcl-2–vitamin D3 complexes exhibited limited backbone fluctuations (Fig. 5). The global RMSF values (Table 4) were 1.545 Å for CDK2 and 1.943 Å for Bcl-2—well below the 3 Å instability threshold. The RMSF plots revealed that key residues involved in ligand interaction—namely, Ile10 (red line), Lys33 (orange line), and Val64 (green line) in CDK2 (Fig. 5A), and Phe101 (red line), Tyr105 (orange line), and Met112 (green line) in Bcl-2 (Fig. B)—exhibited notably low RMSF values. These residues correspond to the ATP-binding pocket in CDK2 and the BH3-binding groove in Bcl-2. Additionally, the Rg remained consistent at 1.000 for both complexes, indicating no significant expansion or contraction in protein size during the simulation (Fig. 6). Furthermore, the RMSD values were 3.638 Å for the CDK2 complex and 3.249 Å for the Bcl-2 complex (Table 4), reflecting moderate but acceptable structural deviations typically observed in coarse-grained MD simulations. According to the ADMET study, vitamin D3 exhibited favorable pharmacokinetic and safety characteristics. Its favorable intestinal absorption (93.784%) and low Caco-2 cell permeability (1.219 log Papp in 10⁻⁶ cm/s) suggest good oral absorption potential. Vitamin D3 also demonstrated moderate blood–brain barrier permeability (0.774 log BB) and low CNS permeability (−1.412 log PS), indicating minimal central nervous system penetration. However, two limitations were identified: its water solubility was notably low (−6.738 log mol/l), and its plasma protein binding was predicted to be complete (fraction unbound=0), potentially reducing the bioavailable free drug in circulation. Despite these challenges, the compound exhibited no significant interaction with P-glycoprotein or major cytochrome P450 enzymes. The metabolism profile identified it as a CYP3A4 substrate but not as an inhibitor of other key CYP enzymes, indicating low potential for metabolic drug–drug interactions. Excretion data showed a total clearance of 0.83 log ml/min/kg with no involvement of the renal OCT2 transporter. Vitamin D3 was predicted to be non-mutagenic, with no hERG I inhibition and only mild hERG II interaction. Vitamin D3 is pharmacologically well-tolerated, as evidenced by values within the acceptable range when the maximum tolerated dose and lowest observed adverse effect level were evaluated. DiscussionIn silico techniques have proven to be useful tools early in the drug discovery process because they provide quick and affordable insights into pharmacokinetic characteristics, binding potential, and molecular interactions. Researchers can effectively prioritize promising therapeutic agents by using computational strategies that simulate the behavior of candidate compounds against particular biological targets before committing to time-consuming and expensive laboratory testing.

Fig. 4. Molecular dynamics model of protein interacted with vitamin D3. (A) CDK2. (B) Bcl-2. The function of vitamin D3 in regulating the expression and activity of carcinogenic proteins, such as Bcl-2 and CDK2, has been previously investigated. Although there is currently no concrete proof that vitamin D3 affects CDK2 in CRC, studies on gastric cancer cells have revealed that it can suppress CDK2 expression via a mechanism that is dependent on the vitamin D receptor (VDR), leading to cell cycle arrest and decreased cell proliferation (Li et al., 2017). Vitamin D3 has also been shown to decrease Bcl-2 expression in the context of colorectal cancer, which may promote apoptosis and slow the growth of the tumor (Almaimani et al., 2022). Nevertheless, the majority of these results emphasize indirect effects, such as upstream signaling pathway modulation or transcriptional regulation (Varghese et al., 2020; Blasiak et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2024). To date, no in silico investigation has specifically examined the simultaneous binding interactions and affinity of vitamin D3 with CDK2 and Bcl-2. Targeting these two proteins in parallel is of particular relevance, as they represent two central hallmarks of CRC: uncontrolled cell proliferation and resistance to apoptosis. Unlike conventional single-target approaches, this study proposes vitamin D3 as a potential dual inhibitor, offering a more integrated strategy to disrupt multiple oncogenic mechanisms. By focusing on CDK2 and Bcl-2 as representative targets, the combined molecular docking and dynamics approach adopted in this study is aligned with current advances in multi-target drug design and provides new insight into the broad-spectrum anticancer potential of vitamin D3.

Fig. 5. RMSF plot of protein interacted with vitamin D3 and highlighted key residue. (A) CDK2. (B) Bcl-2, highlighting key ligand-binding residues—CDK2: Ile10 (red), Lys33 (orange), Val64 (green); Bcl-2: Phe101 (red), Tyr105 (orange), Met112 (green). RMSF values are shown by residue number; colored markers indicate key interaction sites. The dual-target in silico analysis revealed that vitamin D3 demonstrates notable binding potential to both CDK2 and Bcl-2, with binding affinity scores of −9.5 and −.2 kcal/mol, respectively (Table 2), suggesting its suitability as a multi-target anticancer agent. To strengthen the interpretation of these values, we benchmarked the docking performance of vitamin D3 against well-established inhibitors: AZD5438 (CDK2), Navitoclax (Bcl-2), and quercetin (a multi-target phytochemical). AZD5438, a selective ATP-competitive inhibitor of CDK2, exhibited a binding energy of −9.0 kcal/mol, slightly lower than that of vitamin D3 (−9.5 kcal/mol), suggesting that vitamin D3 may occupy the ATP-binding pocket with comparable or even superior affinity. Meanwhile, Navitoclax showed the strongest binding to Bcl-2 at −10.7 kcal/mol, consistent with its established potency as a BH3 mimetic. Although vitamin D3 demonstrated a lower docking score (−8.2 kcal/mol), its ability to bind at the same BH3-binding groove suggests potential for Bcl-2 activity partial inhibition or allosteric modulation. Importantly, while both AZD5438 and Navitoclax exhibit high target specificity, their clinical application has been limited due to adverse effects. In contrast, vitamin D3 is an endogenous compound with a favorable safety profile and low toxicity, making it an attractive candidate for long-term or adjunctive cancer therapy. Table 4. Molecular dynamics simulation parameters of vitamin D3 interaction with CDK-2 and Bcl-2 proteins.

In addition, quercetin was included as a phytochemical control because of its broad-spectrum anticancer properties and its reported interactions with both CDKs and Bcl-2 family proteins. Its moderate docking scores (−9.0 kcal/mol for CDK2, −7.5 kcal/mol for Bcl-2) reflect its polypharmacological nature. Interestingly, vitamin D3 exhibited superior binding interactions with both CDK2 and Bcl-2 compared with quercetin, thereby reinforcing its potential as a dual-targeted anticancer compound with enhanced safety characteristics. CDK2 is crucial for cell cycle regulation, especially during the G1 to S phase transition, and its aberrant activation is significantly linked to the advancement of multiple malignancies, including CRC. Consequently, CDK2 has become a desirable molecular target in the search for innovative anticancer treatments (Shi et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2018; Tadesse et al., 2020). Several ATP-competitive inhibitors—such as AZD5438—have been developed to inhibit this kinase, with some advancing into clinical evaluation. However, despite their initial promise, many of these compounds have shown limited clinical success, primarily due to suboptimal efficacy, adverse side effects, and considerable toxicity (Bogoyevitch et al., 2005; Harrison et al., 2008; Duncan et al., 2012; Olivieri et al., 2022). These limitations highlight the ongoing need for alternative therapeutic agents that offer improved safety profiles and greater anticancer potential.

Fig. 6. Radius of gyration of protein interacted with vitamin D3 and highlighted key residue. (A) CDK2. (B) Bcl-2. To provide a deeper understanding, this study revealed that vitamin D3 binds to CDK2 with high affinity by interacting with key residues located within the ATP-binding pocket, notably Lys89, Val64, and Ile10 (Table 3). Lys89 is crucial for improving the binding strength and selectivity of inhibitors; it creates temporary hydrogen bonds specific to CDK2 that help set it apart from other kinases like CDK4 (Talapati et al., 2021). Val64 helps to stabilize the ATP-CDK2 complex by forming robust hydrophobic and van der Waals interactions that firmly anchor ATP within the catalytic domain. By strengthening these hydrophobic interactions, Ile10 also aids in maintaining the correct orientation of ATP in the binding site, protecting the structural integrity and catalytic activity of the enzyme (Rout et al., 2019). It is conceivable that vitamin D3 shares an active site with ATP and, like traditional ATP-competitive inhibitors, uses a competitive mechanism to produce its inhibitory effect based on this binding pattern. Considering its natural source and proven safety record (Gaby and Singh, 2024; Nekoukar et al., 2024), with a lower chance of side effects, vitamin D3 offers a strong substitute for synthetic CDK2 inhibitors. Furthermore, it was discovered that the residues Phe101, Tyr105, and Met112 of the Bcl-2 protein structure interact with vitamin D3 (Table 3). The BH3-binding groove, a conserved hydrophobic cleft on the Bcl-2 surface that is crucial for regulating apoptosis, depends on these residues. The pro-apoptotic proteins Bim and Bid’s BH3 domains are bound by this groove, which inhibits Bcl-2’s pro-survival function and initiates programmed cell death (Reddy et al., 2020). In particular, Met112 stabilizes the interaction by being a component of the hydrophobic core, while Phe101 and Tyr105 help to create the hydrophobic environment necessary for effective BH3 domain recognition (Joseph et al., 2004). Vitamin D3’s capacity to occupy this groove points to a mechanism of action akin to that of BH3 mimetics, such as Navitoclax, which are intended to displace pro-apoptotic proteins and restore apoptotic signaling in cancer cells. Unlike Navitoclax, which is known has the ability to inhibit Bcl-XL and causes thrombocytopenia, vitamin D3 interacts with the BH3-binding groove without producing similar hematological adverse effects. This difference shows its promise as a safer substitute for modifying anti-apoptotic pathways (Wang et al., 2008; Mhaibes and Abdul- Wahab2, 2023). The ability of vitamin D3 to bind to the BH3 groove without causing negative effects highlights its potential as a less risky option for addressing anti-apoptotic pathways. The residue-level RMSF analysis (Table 4) supports the hypothesis that vitamin D3 forms stable and well-retained interactions with both CDK2 and Bcl-2. In the CDK2 complex, residues such as Ile10, Lys33, and Val64—within the core ATP-binding cleft—exhibited minimal atomic fluctuations throughout the simulation (Fig. 5A), suggesting a structurally rigid and functionally preserved pocket during ligand engagement. Similarly, Phe101, Tyr105, and Met112 in the Bcl-2 complex (Fig. 5B), located within the BH3-binding groove, also showed low RMSF values, reflecting conformational stability at the binding interface. In addition to localized residue stability, the Rg values for both complexes remained at 1.000, confirming global structural compactness and the absence of unfolding events (Fig. 6). Complementing this, the RMSD values for CDK2 (3.638 Å) and Bcl-2 (3.249 Å) (Table 4) were within a reasonable range for coarse-grained dynamics, suggesting that the general structure of the complexes was steady during the simulation period, although some fluctuations occurred. All of these results support the structural validity of the anticipated docking positions and demonstrate how vitamin D3 interacts with conserved, functionally important domains in a stable, dynamic manner. According to our in silico ADMET prediction, vitamin D3 demonstrates several pharmacokinetic advantages that support its potential as a treatment agent for CRC. It shows high intestinal absorption (93.78%) and favorable Caco-2 permeability, indicating promising oral bioavailability. Moreover, it is neither a substrate for P-glycoprotein nor an inhibitor of key cytochrome P450 enzymes (CYP1A2, CYP2C19, CYP2C9, CYP2D6, and CYP3A4), indicating a low likelihood of metabolic drug-drug interactions via cytochrome P450 pathways, which enhances its compatibility in combination regimens for CRC. The predicted clearance rate (0.83 log ml/min/kg) supports feasible dosing regimens, while the absence of renal OCT2 transporter interaction reduces the likelihood of renal complications. Despite these favorable properties, two notable pharmacokinetic limitations were identified. The water solubility of vitamin D3 is extremely low (−6.738 log mol/l), which may hinder its dissolution and absorption in the gastrointestinal tract. Second, its plasma protein binding is predicted to be very high (fraction unbound=0), indicating that the compound is entirely bound in circulation, potentially reducing the concentration of free, bioactive drug. These characteristics may impair its effective systemic delivery, necessitating formulation strategies—such as nanoparticle encapsulation or lipid-based carriers—to improve bioavailability. Furthermore, vitamin D3 exhibits a favorable safety profile, with no AMES toxicity, no CYP inhibition, and acceptable acute and chronic toxicity levels. Although one hERG II inhibition was predicted, no inhibition was observed for hERG I, suggesting limited cardiotoxicity. All of these results offer compelling evidence for the advancement of vitamin D3 as a treatment option for CRC, especially when combined with delivery methods that are optimized to get around the vitamin’s high protein binding and solubility issues. Building on these discoveries, these results offer a strong case for more research into vitamin D3 as a multi-target therapeutic agent that may have fewer adverse effects than traditional inhibitors. To close the gap between computational predictions and biological relevance, experimental validation remains crucial. Dissociation constants (Kd) and real-time binding kinetics can be measured using methods such as surface plasmon resonance, which provide concrete proof of molecular interaction. The thermodynamic parameters controlling the binding process are revealed by isothermal titration calorimetry, and thermal shift assays make it possible to evaluate the ligand-induced stabilization of target proteins. These biophysical techniques are frequently used in early-stage drug discovery and are especially useful for confirming theories derived from docking (Bernacchi and Ennifar, 2020; Saridakis and Coste, 2021; Sun et al., 2023). Using these methods, the potential of vitamin D3e as a dual-target therapeutic agent for CRC may be strengthened by determining whether it can bind to CDK2 and Bcl-2 both functionally and selectively under physiologically relevant circumstances. ConclusionThis work highlights the potential of vitamin D3 to act as a dual inhibitor of CDK2 and Bcl-2, two important molecular drivers in the pathophysiology of CRC. Its potential for dual-pathway therapeutic approaches in CRC is highlighted by its stable binding interactions, desirable ADMET properties, and capacity to influence cell proliferation and apoptosis simultaneously. Previous studies have reported that vitamin D3 reduces CDK2 and Bcl-2 expression levels or modulates their signaling cascades. Although these studies confirm its biological impact, they predominantly represent indirect regulatory effects. Further validation using biophysical techniques should be conducted to confirm the direct binding interactions predicted in this computational analysis, followed by more in-depth investigations through in vitro and in vivo studies. These experimental approaches will be essential for establishing a clearer mechanistic understanding and further supporting the potential of vitamin D3 as a natural, multi-target therapeutic agent for CRC. AcknowledgementsThis work was supported by the Indonesia Endowment Fund for Education (LPDP). Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no competing interests. FundingThis work was supported by the Indonesia Endowment Fund for Education (LPDP), Ministry of Finance of the Republic of Indonesia, Grant Number 202312211582593. Authors’ contributionsThe experiments were conceived and designed by Jauharotus Shobahah and Sri Puji Astuti Wahyuningsih. Jauharotus Shobahah and Mochammad Aqilah Herdiansyah performed the experiments. Jauharotus Shobahah, Mochammad Aqilah Herdiansyah, M. Ainun Najib Aly, and Dwi Winarni participated in the data analysis. Jauharotus Shobahah and Sri Puji Astuti Wahyuningsih drafted the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript. Data availabilityAll data supporting the findings of this study are available within the manuscript. AbbreviationsADMET, absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, toxicity; Bcl-2, B-cell lymphoma 2; CDK2, cyclin-dependent kinase 2; CRC, colorectal cancer; Rg, radius of gyration; RMSD, root mean square deviation; RMSF, root mean square fluctuation. REFERENCEAlam, M., Ali, S., Mohammad, T., Hasan, G.M., Yadav, D.K. and Hassan, M.I. 2021. B cell lymphoma 2: a potential therapeutic target for cancer therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22(19), 10442; doi:10.3390/ijms221910442 Alifiansyah, M.R., Herdiansyah, M.A., Pratiwi, R.C., Pramesti, R.P., Hafsyah, N.W., Rania, A.P., Putra, J.E., Cahyono, P.A., Muhammad, S.K., Murtadlo, A.A. and Kharisma, V.D. 2024. QSAR of acyl alizarin red biocompound derivatives of rubia tinctorumu roots and Its ADMET properties as anti-breast cancer candidates against MMP-9 protein receptor: in silico study. Food Syst. 7(2), 312–320; doi:10.21323/2618-9771-2024-7-2-312-320 Almaimani, R.A., Aslam, A., Ahmad, J., El-Readi, M.Z., El-Boshy, M.E., Abdelghany, A.H., Idris, S., Alhadrami, M., Althubiti, M., Almasmoum, H.A., Ghaith, M.M., Elzubeir, M.E., Eid, S.Y. and Refaat, B. 2022. In vivo and in vitro enhanced tumoricidal effects of metformin, active vitamin D3, and 5-fluorouracil triple therapy against colon cancer by modulating the PI3K/Akt/PTEN/mTOR network. Cancers 14(6), 1538; doi:10.3390/cancers14061538 Banjare, P., Sarthi, A.S., Singh, J. and Roy, P.P. 2020. In-silico approaches in drug discovery and design of anti-allergic agents. Front. Clin. Drug Res. - Anti Allergy Agents. 4, 94; doi:10.2174/9789811428395120040006 Bernacchi, S. and Ennifar, E. 2020. Analysis of the HIV-1 genomic RNA dimerization initiation site binding to aminoglycoside antibiotics using isothermal titration calorimetry. Methods Mol. Biol. 2113, 237–250. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-0716-0278-2_16 Bhati, A.P., Wan, S., Alfè, D., Clyde, A.R., Bode, M., Tan, L., Titov, M., Merzky, A., Turilli, M., Jha, S. and Highfield, R.R. 2021. Pandemic drugs at pandemic speed: infrastructure for accelerating COVID-19 drug discovery with hybrid machine learning- and physics-based simulations on high-performance computers. Interface Focus 11(6), 20210018; doi: 10.1098/rsfs.2021.0018 Bisht, N., Sah, A.N., Bisht, S. and Joshi, H. 2021. Emerging need of today: significant utilization of various databases and softwares in drug design and development. Mini. Rev. Med. Chem. 21(8), 1025–1032; doi:10.2174/1389557520666201214101329 Blasiak, J., Chojnacki, J., Pawlowska, E., Jablkowska, A. and Chojnacki, C. 2022. Vitamin D may protect against breast cancer through the regulation of long noncoding RNAs by VDR signaling. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23(6), 3189; doi:10.3390/ijms23063189 Bogoyevitch, M.A., Barr, R.K. and Ketterman, A.J. 2005. Peptide inhibitors of protein kinases—discovery, characterisation and use. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1754(1–2), 79–99; doi:10.1016/j.bbapap.2005.07.025 Duncan., James, S., Timothy AJ Haystead. and David W Litchfield. 2012. Chemoproteomic characterization of protein kinase inhibitors using immobilized ATP. Methods. Mol. Biol. 795, 119–134; doi:10.1007/978-1-61779-337-0_8 Gaby, S.K. and Singh, V.N. 2024. Vitamin D. In Vitamin intake and health, Boca Raton: CRC Press, pp: 59–70; doi:10.1201/9781003573777-4. Harrison, S., Das, K., Karim, F., Maclean, D. and Mendel, D. 2008. Non-ATP-competitive kinase inhibitors - enhancing selectivity through new inhibition strategies. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 3(7), 761–774; doi:10.1517/17460441.3.7.761 Herdiansyah, M.A., Rizaldy, R., Alifiansyah, M.R., Fetty, A.J., Anggraini, D., Agustina, N., Alfian, F.R., Setianingsih, P.N., Elfianah, V., Aulia, H.S., Putra, J.E., Ansori, A.N., Kharisma, V.D., Jakhmola, V., Purnobasuki, H., Pratiwi, I.A., Rebezov, M., Shmeleva, S., Bonkalo, T., Kovalchuk, D.F. and Zainul, R. 2024. Molecular interaction analysis of ferulic acid (4-hydroxy-3-methoxycinnamic acid) as main bioactive compound from palm oil waste against MCF-7 receptors: an in silico study. Narra. J. 4(2), e775; doi:10.52225/narra.v4i2.775 Joseph, M.K., Solomon, L.R., Petros, A.M., Cai, J., Simmer, R.L., Zhang, H., Rosenberg, S. and Ng, S.C. 2004. Divergence of Genbank and human tumor Bcl-2 sequences and implications for binding affinity to key apoptotic proteins. Oncogene 23(3), 835–838; doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1207141 Li, M., Li, L., Zhang, L., Hu, W., Shen, J., Xiao, Z., Wu, X., Chan, F.L. and Cho, C.H. 2017. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 suppresses gastric cancer cell growth through VDR- and mutant p53-mediated induction of p21. Life Sci. 179, 88–97; doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2017.04.021 Mhaibes, A.M. and Abdul- Wahab2, F.K. 2023. Possible effects of vitamin D3 and levofloxacin on selected hematology parameter of rats. Iraqi J. Pharm. Sci. 32, 74–84; doi:10.31351/vol32issSuppl.pp74-84 Nekoukar, Z., Manouchehri, A. and Zakariaei, Z. 2024. Accidental vitamin D3 overdose in a young man. Int. J. Vitamin Nutr. Res. 94(2), 82–85; doi:10.1024/0300-9831/a000798 Olivieri, C., Li, G.C., Wang, Y., VS, M., Walker, C., Kim, J., Camilloni, C., De Simone, A., Vendruscolo, M., Bernlohr, D.A. and Taylor, S.S. 2022. ATP-competitive inhibitors modulate the substrate binding cooperativity of a kinase by altering its conformational entropy. Sci. Adv. 8(30), eabo0696. doi:10.1126/sciadv.abo0696. Reddy, C.N., Manzar, N., Ateeq, B. and Sankararamakrishnan, R. 2020. Computational design of BH3-mimetic peptide inhibitors that can bind specifically to Mcl-1 or Bcl-XL: role of non-hot spot residues. Biochemistry 59(45), 4379–4394; doi:10.1021/acs.biochem.0c00661 Roshandel, G., Ghasemi-Kebria, F. and Malekzadeh, R. 2024. Colorectal Cancer: epidemiology, risk factors, and prevention. Cancers 16(8), 1530; doi:10.3390/cancers16081530 Rout, A.K., Mishra, J., Dehury, B., Maharana, J., Acharya, V., Karna, S.K., Parida, P.K., Behera, B.K. and Das, B.K. 2019. Structural bioinformatics insights into ATP binding mechanism in zebrafish (Danio rerio) cyclin-dependent kinase-like 5 (zCDKL5) protein. J. Cell. Biochem. 120(6), 9437–9447; doi:10.1002/jcb.28219 Samuel, S. and Sitrin, M.D. 2008. Vitamin D’s role in cell proliferation and differentiation. Nutr. Rev. 66, S116–S124; doi:10.1111/j.1753-4887.2008.00094.x Saridakis, E. and Coste, F. 2021. Thermal shift assay for characterizing the stability of RNA helicases and their interaction with ligands. Mol. Med. Rep. 2209, 73–85; doi:10.1007/978-1-0716-0935-4_5. Shi, X.N., Li, H., Yao, H., Liu, X., Li, L., Leung, K.S., Kung, H.F. and Lin, M.C.M. 2015. Adapalene inhibits the activity of cyclin-dependent kinase 2 in colorectal carcinoma. Mol. Med. Rep. 12(5), 6501–6508; doi:10.3892/mmr.2015.4310 Sun, Binmei, Jianmei Xu, Shaoqun Liu, and Qing X. Li. 2023. Characterization of small molecule–protein interactions using SPR method. Methods Mol. Biol. 2690, 149–159; doi:10.1007/978-1-0716-3327-4_15 Tadesse, S., Anshabo, A.T., Portman, N., Lim, E., Tilley, W., Caldon, C.E. and Wang, S. 2020. Targeting CDK2 in cancer: challenges and opportunities for therapy. Drug Discov. Today 25(2), 406–413; doi:10.1016/j.drudis.2019.12.001 Talapati, S.R., Goyal, M., Nataraj, V., Pothuganti, M., Sreevidya, M.R., Gore, S., Ramachandra, M., Antony, T., More, S.S. and Rao, N.K. 2021. Structural and binding studies of cyclin‐dependent Kinase 2 with NU6140 inhibitor. Chem. Biol. Drug Design 98(5), 857–868; doi:10.1111/cbdd.13941 Tukaram Patil, S., Wilfred Devadass, C. and Shetty Badila, P. 2019. Histopathological evaluation and analysis of immunohistochemical expression of Bcl-2 oncoprotein in colorectal carcinoma. Iranian J. Pathol. 14(4), 317–321; doi:10.30699/IJP.2019.102982.2028 Varghese, J.E., Shanmugam, V., Rengarajan, R.L., Meyyazhagan, A., Arumugam, V.A., Al-Misned, F.A. and El-Serehy, H.A. 2020. Role of vitamin D3 on apoptosis and inflammatory-associated gene in colorectal cancer: an in vitro approach. J. King Saud Univ. - Sci. 32(6), 2786–2789; doi:10.1016/j.jksus.2020.06.015 Wang, J., Lian, H., Zhao, Y., Kauss, M.A. and Spindel, S. 2008. Vitamin D3 induces autophagy of human myeloid leukemia cells. J. Biol. Chem. 283(37), 25596–25605. Wang, Y., He, Q., Rong, K., Zhu, M., Zhao, X., Zheng, P. and Mi, Y. 2024. Vitamin D3 promotes gastric cancer cell autophagy by mediating p53/AMPK/mTOR signaling. Front. Pharmacol. 14, 1338260; doi:10.3389/fphar.2023.1338260 Weiswald, L.B., Hasan, M.R., Wong, J.C.T., Pasiliao, C.C., Rahman, M., Ren, J., Yin, Y., Gusscott, S., Vacher, S., Weng, A.P., Kennecke, H.F., Bièche, I., Schaeffer, D.F., Yapp, D.T. and Tai, I.T. 2017. Inactivation of the kinase domain of CDK10 prevents tumor growth in a preclinical model of colorectal cancer, and is accompanied by downregulation of Bcl-2. Mol. Cancer Ther. 16(10), 2292–2303; doi:10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-16-0666 Yasmeen, A., Berdel, W.E., Serve, H. and Müller-Tidow, C. 2003. E- and A-type cyclins as markers for cancer diagnosis and prognosis. Expert Rev. Mol. Diagn. 3(5), 617–633; doi:10.1586/14737159.3.5.617 Zhang, X., Zhao, Y., Wang, C., Ju, H., Liu, W., Zhang, X., Miao, S., Wang, L., Sun, Q. and Song, W. 2018. Rhomboid domain-containing protein 1 promotes breast cancer progression by regulating the p-Akt and CDK2 levels. Cell Commun. Signal. 16(1), 65; doi:10.1186/s12964-018-0267-5 Zhou, J., Ge, X., Fan, X., Wang, J., Miao, L. and Hang, D. 2021. Associations of vitamin D status with colorectal cancer risk and survival. Int. J. Cancer 149(3), 606–614; doi:10.1002/ijc.33580 | ||

| How to Cite this Article |

| Pubmed Style Shobahah J, Wahyuningsih SPA, Winarni D, Herdiansyah MA, Aly MAN. In silico evaluation of vitamin D3 as a dual inhibitor of CDK2 and Bcl-2 in colorectal cancer. Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(8): 3759-3769. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i8.40 Web Style Shobahah J, Wahyuningsih SPA, Winarni D, Herdiansyah MA, Aly MAN. In silico evaluation of vitamin D3 as a dual inhibitor of CDK2 and Bcl-2 in colorectal cancer. https://www.openveterinaryjournal.com/?mno=265321 [Access: January 25, 2026]. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i8.40 AMA (American Medical Association) Style Shobahah J, Wahyuningsih SPA, Winarni D, Herdiansyah MA, Aly MAN. In silico evaluation of vitamin D3 as a dual inhibitor of CDK2 and Bcl-2 in colorectal cancer. Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(8): 3759-3769. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i8.40 Vancouver/ICMJE Style Shobahah J, Wahyuningsih SPA, Winarni D, Herdiansyah MA, Aly MAN. In silico evaluation of vitamin D3 as a dual inhibitor of CDK2 and Bcl-2 in colorectal cancer. Open Vet. J.. (2025), [cited January 25, 2026]; 15(8): 3759-3769. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i8.40 Harvard Style Shobahah, J., Wahyuningsih, . S. P. A., Winarni, . D., Herdiansyah, . M. A. & Aly, . M. A. N. (2025) In silico evaluation of vitamin D3 as a dual inhibitor of CDK2 and Bcl-2 in colorectal cancer. Open Vet. J., 15 (8), 3759-3769. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i8.40 Turabian Style Shobahah, Jauharotus, Sri Puji Astuti Wahyuningsih, Dwi Winarni, Mochammad Aqilah Herdiansyah, and M Ainun Najib Aly. 2025. In silico evaluation of vitamin D3 as a dual inhibitor of CDK2 and Bcl-2 in colorectal cancer. Open Veterinary Journal, 15 (8), 3759-3769. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i8.40 Chicago Style Shobahah, Jauharotus, Sri Puji Astuti Wahyuningsih, Dwi Winarni, Mochammad Aqilah Herdiansyah, and M Ainun Najib Aly. "In silico evaluation of vitamin D3 as a dual inhibitor of CDK2 and Bcl-2 in colorectal cancer." Open Veterinary Journal 15 (2025), 3759-3769. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i8.40 MLA (The Modern Language Association) Style Shobahah, Jauharotus, Sri Puji Astuti Wahyuningsih, Dwi Winarni, Mochammad Aqilah Herdiansyah, and M Ainun Najib Aly. "In silico evaluation of vitamin D3 as a dual inhibitor of CDK2 and Bcl-2 in colorectal cancer." Open Veterinary Journal 15.8 (2025), 3759-3769. Print. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i8.40 APA (American Psychological Association) Style Shobahah, J., Wahyuningsih, . S. P. A., Winarni, . D., Herdiansyah, . M. A. & Aly, . M. A. N. (2025) In silico evaluation of vitamin D3 as a dual inhibitor of CDK2 and Bcl-2 in colorectal cancer. Open Veterinary Journal, 15 (8), 3759-3769. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i8.40 |