| Research Article | ||

Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(9): 4128-4135 Open Veterinary Journal, (2025), Vol. 15(9): 4128-4135 Research Article Histological evaluation of thermosensory receptors and cutaneous neurovascular in the tail skin of BALB/c miceNuha Shaker Ali*Department of Basic Science, Dentistry College, University of Al-Qadisiyah, Iraq *Corresponding Author: Nuha Shaker Ali. Department of Basic Science, Dentistry College, University of Al-Qadisiyah, Al Diwaniyah, Iraq. Email: nuha.albadry [at] qu.edu.iq Submitted: 18/06/2025 Revised: 20/08/2025 Accepted: 30/08/2025 Published: 30/09/2025 © 2025 Open Veterinary Journal

ABSTRACTBackground: Thermosensory receptors in cutaneous tissues regulate body temperature. The mouse tail contains a dense network of sensory neurons that participate in temperature detection. Histological mapping of these receptors remains limited. Aim: This study aimed to examine the histological features, neural pathways, and gene activity related to thermosensory function in the dorsal tail skin of mice. Methods: Eighteen male Bagg Albino (BALB)/c mice were used. The tail skin was exposed to cold or warm stimulation. Samples were collected from the skin, spinal cord, and hypothalamus. Hematoxylin and eosin and silver staining were performed. Immunofluorescence was used to identify TRPM8- and TRPV1-positive neurons. ChIP-qPCR was used to assess histone modifications. Gene expression for TRPM8 and TRPV1 was analyzed by RT-qPCR. High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) was used to measure neuropeptides. Results: Histology revealed thicker dermal layers and visible vascular and nerve changes in both cold- and heat-treated skin compared with controls. Silver staining revealed increased nerve fiber (NF) density in stimulated groups. Immunofluorescence confirmed significant TRPM8 expression after cold exposure and TRPV1 expression after heat exposure, localized along dermal NFs. RT-qPCR showed a clear, significant upregulation of TRPM8 and TRPV1 genes. ChIP-qPCR revealed significantly increased histone acetylation (H3K27ac) and decreased methylation (H3K9me3) in the hypothalamus after stimulation, indicating chromatin activation. HPLC results showed elevated levels of Substance P and β-Endorphin in stimulated tissues. Conclusion: Thermal stimulation activates both peripheral and central pathways involving thermoreceptors, neuropeptides, and gene regulation. This study also shows how simple thermal exposure can alter nerve density and neurochemical signals. Thermal stimuli activate clear histological, molecular, and epigenetic responses in BALB/c mice that link the skin and brain. Keywords: Thermoreceptors; Histology; Immunofluorescence; BALB/c mice; Thermal stimulation. IntroductionThe hypothalamus controls several vital functions in mammals. Its main structure includes multiple nuclei that regulate body temperature, hunger, sleep, and hormonal secretion (Dudás, 2021). The organization of the hypothalamus is highly complex, with many regions lacking sharp boundaries between the nuclei. The paraventricular and arcuate nuclei, which integrate signals from peripheral organs and central circuits, are among its important parts (Nagpal et al., 2019; Song and Choi, 2023). The arcuate nucleus contains neuroendocrine and projecting neurons that contribute to both homeostatic and behavioral functions. The hypothalamus receives direct input from the skin via sensory pathways, which link external environmental cues to internal regulatory systems (Fong et al., 2023). The hypothalamus helps regulate body temperature by processing sensory neuron signals. It also works through the HPT axis to support this control. Some sleep-related brain networks in the hypothalamus may also affect body functions such as heart rate and hormones. The skin comprises three main layers: epidermis, dermis, and hypodermis. The epidermis’ outer layer acts as a barrier. The dermis contains blood vessels, nerves, and sensory receptors. The hypodermis contains fat and helps with insulation. Sensory nerves in the skin detect heat, cold, and touch changes. These signals travel through peripheral nerves to the spinal cord and brain. This neural link allows the body to respond quickly to changes in temperature and protect itself (Feldt-Rasmussen et al., 2021; Adamantidis and de Lecea, 2023). The skin is connected to the Central nervous system (CNS) through specific sensory and autonomic pathways. Sensory neurons in the skin detect thermal and mechanical signals and send them to the spinal cord through the dorsal root ganglia. From there, the signals reach the hypothalamus for processing. Autonomic nerves also send signals back to the skin to control blood flow, sweating, and piloerection. This feedback loop helps maintain body temperature and skin function (May et al., 2018; Christ-Crain et al., 2019; Maita et al., 2021). Thermosensory receptors in the skin regulate body temperature by sending signals to the brain. These signals reach the hypothalamus, which adjusts heat loss and production. Although this function is well known, the exact neural routes and molecular changes between the skin and hypothalamus have not been fully mapped. The skin connects with the CNS through defined sensory and autonomic pathways. These include the dorsal root ganglia and spinal cord circuits that are linked to the hypothalamic centers. Autonomic fiber feedback also controls blood flow and sweating in the skin. However, the full pattern of these pathways and their activation during thermal stress remains unclear. Scientists use animal models and detailed anatomy studies to understand these pathways (Lakomá et al., 2016; Richards, 2018; Vivier et al., 2018; Lu et al., 2021). Previous research has focused more on brain regions than on peripheral skin receptors. Imaging and tracing studies have shown general sensory input to hypothalamic areas, but specific thermosensory maps are lacking (Nagpal et al., 2019; Chapman et al., 2020; Asa et al., 2022; Song and Choi, 2023). This study addresses this gap by focusing on the tail skin of Bagg Albino (BALB)/c mice, a site rich in thermosensory neurons. This study aimed to identify the structure and activity of TRPM8 and TRPV1 receptors during cold and warm exposure. This study also investigates how these signals affect hypothalamic changes and neuropeptide release. Histology, immunofluorescence, gene expression analysis, and chemical detection tools were used to explore the sensory-brain-hormone connection. By combining structural, neural, and molecular data, this study reveals how skin-based thermal signals influence central temperature control. Materials and MethodsAnimalsEighteen male BALB/c mice (10 weeks old, 22–25 g) were purchased from a local animal house facility. Mice were housed in a private animal house center in Al-Diwaniyah City, Iraq, under controlled conditions (22°C ± 2°C, 12 hours light/dark cycle) with free access to standard chow and water and an acclimatization period of 14 days. Experimental groupsThe mice were randomly divided into three groups: control group A (n=6), cold stimulation group B (n=6), and heat stimulation group C (n=6). Thermal stimulationFor cold exposure, the distal tail was immersed in 10°C water for 5 minutes daily for 3 consecutive days. The distal tail was immersed in 42°C water under identical conditions for heat exposure. The control animals received no stimulation. The study was conducted over a period of 8 weeks. This included animal preparation, thermal stimulation, sample collection, and laboratory analysis. Methods were followed from Caterina et al. (2000), Mckemy et al. (2002), and Andrè et al. (2008). Tissue collectionThe mice were deeply anesthetized with ketamine (80 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg). Once fully unconscious, they were euthanized by an intraperitoneal overdose of sodium pentobarbital (200 mg/kg). Tissues from the tail skin, spinal cord, and hypothalamus were then collected. Some samples were fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde, whereas others were frozen and stored at 80°C for later tests. Histology and stainingParaffin-embedded tissues were sectioned at 5 μm thickness using a rotary microtome. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining was performed to assess the general tissue structure. Bielschowsky’s silver stain was used to highlight and visualize nerve fibers (NFs) within the skin and spinal cord samples. ImmunofluorescenceTail skin tissue samples were embedded in optical coherence tomography and cryosectioned at 10 μm thickness using a cryostat. Sections were fixed in 4% cold paraformaldehyde for 10 min and then washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Blocking was performed with 5% normal goat serum in 0.3% Triton X-100 for 1 hour at room temperature. Primary antibodies against TRPM8 and TRPV1 were applied at 4°C overnight. After washing, sections were incubated with Alexa Fluor 488 or 594-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:500, Invitrogen) in the dark for 1 hour at room temperature. Nuclei were stained with DAPI (1 μg/ml) for 5 minutes. Anti-TRPM8 (rabbit monoclonal, Cat# ab3243, Abcam, UK; dilution 1:200) and anti-TRPV1 (mouse monoclonal, Cat# sc-398417, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, USA; dilution 1:100) antibodies were used. All antibodies were diluted in PBS with 1% bovine serum albumin unless otherwise stated. Fluorescence intensity and positive cells were quantified using ImageJ (Fiji) software. RNA extraction and RT-qPCRRNA was extracted from the hypothalamic samples using TRIzol (Invitrogen). The High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems) was used for cDNA synthesis. RT-qPCR was performed using SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, USA) on a QuantStudio 5 system. Hypothalamic tissues were homogenized using a sterile RNase-free pestle and microcentrifuge tubes in 1 ml of TRIzol™ Reagent (Invitrogen, USA). Homogenates were incubated at room temperature for 5 minutes. Subsequently, 200 μl of chloroform was added, shaken vigorously for 15 seconds, and incubated for 3 minutes. The samples were centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 15 minutes at 4°C. The aqueous phase was transferred, and RNA was precipitated with isopropanol, washed with 75% ethanol, and dissolved in RNase-free water. The purity and concentration of RNA were measured using a NanoDrop™ 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). Only samples with an A260/A280 ratio between 1.8 and 2.0 were used. cDNA synthesis was performed using 1 µg of RNA with the High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions in a thermal cycler (Eppendorf, Germany). RT-qPCR was carried out using PowerUp™ SYBR™ Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, USA) in a 20 µl reaction on a QuantStudio™ 5 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, USA). Cycling conditions were as follows: 95°C for 2 minutes, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 seconds and 60°C for 1 minute. TRPM8 and TRPV1 were the target genes. Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase was used as the internal control. Relative gene expression was calculated using the 2-ΔΔCt method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001). Primers usedTRPM8: F: CCAAGGAGTTTCCAACAGACG; R: CGTGGCTTCAAAGCAAAGTTT (NM_134252), TRPV1: F: CCGGCTTTTTGGGAAGGGT; GAGACAGGTAGGTCCATCCAC (NM_001001445), Fos: F: CGGGTTTCAACGCCGACTA; R: TGGCACTAGAGACGGACAGAT (NM_010234), NR3C1: F: GACTCCAAAGAATCCTTAGCTCC; R: CTCCACCCCTCAGGGTTTTAT (NM_008173), BDNF: F: TCATACTTCGGTTGCATGAAGG; R: ACACCTGGGTAGGCCAAGTT (NM_001048141), and β-Actin: F: GTGACGTTGACATCCGTAAAGA R: GCCGGACTCATCGTACTCC (NM_007393). Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP-qPCR)ChIP was performed using the SimpleChIP® Enzymatic Chromatin IP Kit (Cell Signaling Technology, #9003, USA). Hypothalamic tissues were chopped on ice and crosslinked with 1% formaldehyde at room temperature for 10 minutes. Glycine (125 mM) was added to prevent crosslinking. Samples were washed in PBS and lysed to isolate nuclei using the lysis buffers provided in the kit. Nuclei were digested with micrococcal nuclease for 20 minutes at 37°C and briefly sonicated to shear chromatin. Chromatin was immunoprecipitated overnight at 4°C using 5 µg of H3K27ac (#8173, Cell Signaling Technology, USA) or H3K9me3 (#13969, Cell Signaling Technology, USA) antibody. A negative control (IgG) was included. DNA was purified using spin columns and used as a template for qPCR. SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, USA) was used for amplification. Primers were designed to target the promoter regions of the TRPM8 and TRPV1 genes. Enrichment was calculated as a percentage of input, and data were normalized to control IgG levels. HPLC analysisThe hypothalamic tissues were homogenized in ice-cold 0.1 M perchloric acid using a glass tissue grinder. The samples were centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 15 minutes at 4°C. The clear supernatant was collected and filtered through a 0.22 µm syringe filter. HPLC was performed using the Agilent 1260 Infinity II system (Agilent Technologies, USA). A ZORBAX Eclipse Plus C18 reversed-phase column (4.6 × 150 mm, 5 µm) was used for separation. Mobile phase A was 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) in water, and mobile phase B was 0.1% TFA in acetonitrile. Gradient elution was applied from 10% to 60% B over 20 minutes at a flow rate of 1.0 ml/min. Detection was performed at 214 nm using a UV detector. The substance P and β-Endorphin standards (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) were used for the calibration. Retention times and peak areas were used to quantify peptide levels. Statistical analysisStatistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism version 10 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). Data were first checked for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk test. One-way analysis of variance was applied for group comparisons, followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. A p-value of 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All data were stored in Microsoft Excel spreadsheets with clear labeling of groups and sample group with ID. Graphs and summary statistics were generated directly using GraphPad Prism. Ethical approvalThe Institutional Animal Ethics Committee approved the experimental protocol (1222 on 01/4/2024). ResultsHistological evaluation of tail skin structureH&E staining clearly revealed the structural layers of the tail skin across all groups. In the control group, the epidermis appeared as a thin, stratified squamous keratinized layer with a compact dermis containing scattered NFs and regular connective tissue. The hypodermis exhibited organized fat layers with no signs of thermal stress (Fig. 1A). In the cold-stimulated group, the dermis exhibited a thicker appearance, with visible sensory NFs extending toward the epidermis (Fig. 1B). The heat-stimulated skin also showed thickened dermal layers, dilated blood vessels, and more prominent nerve profiles (Fig. 1C).

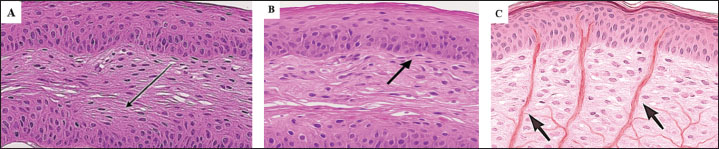

Fig. 1. H&E staining of the tail skin sections of BALB/c mice showing structural differences between the control (A), cold-stimulated (B), and heat-stimulated (C) groups. Arrows point to the dermal NFs. Scale bar=100 µm. Silver staining further demonstrated changes in NF density across groups. Silver-stained fibers were sparse and loosely arranged in the dermis of control mice (Fig. 2A). In contrast, both cold and heat exposure led to a marked increase in small, darkly stained NFs. The cold-stimulated group showed dense, fine networks near the dermal-epidermal junction (Fig. 2B), whereas the heat-stimulated group had thicker, clustered fibers throughout the dermis (Fig. 2C).

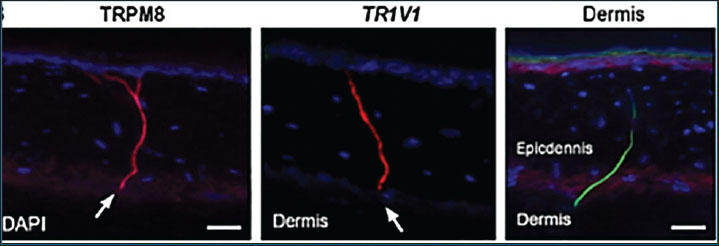

Fig. 2. Silver-stained sections of tail skin showing NF distribution in the control (A), cold-stimulated (B), and heat-stimulated (C) groups. The fiber density increased after stimulation. Scale bar=50 µm. Immunofluorescence staining revealed temperature-specific thermosensory receptor expression in all groups. TRPM8 and TRPV1 were weakly expressed along dermal nerve endings in the control group. Cold stimulation significantly increased TRPM8 expression, as evidenced by the intense green signals in the NFs within the mid to lower dermis. Heat stimulation led to elevated TRPV1 expression, which was observed as a strong red signal in the superficial and mid-dermal layers. The co-localization of these receptors with NFs highlights their role in thermal detection. Figure 3 shows the distribution and intensity differences among groups.

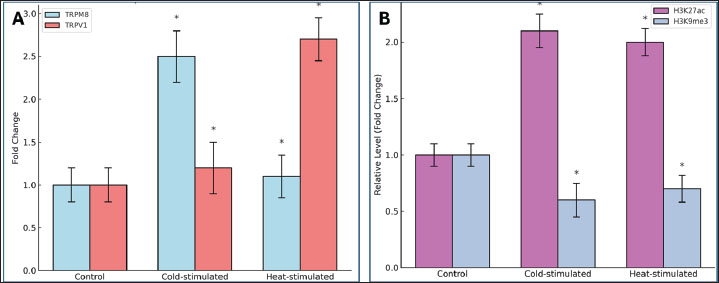

Fig. 3. Immunofluorescence images showing TRPM8 (green) and TRPV1 (red) expression in the tail skin across the control, cold-stimulated, and heat-stimulated groups. Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). Increased receptor signals are visible in tissues treated thermally. Scale bar=50 μm. Quantification of mRNA expression of TRPM8 and TRPV1Gene expression was measured using RT-qPCR. Fold change was calculated by comparing gene expression in the stimulated groups to that in the control animals using the 2−ΔΔCt method. Cold stimulation increased TRPM8 mRNA to approximately 5.8-fold above the control. Heat stimulation caused a 5.5-fold increase in TRPV1 mRNA levels. TRPM8 expression showed only a minor increase after heat stimulation, whereas TRPV1 expression remained near baseline in cold-treated mice. These changes were statistically significant (Fig. 4A).

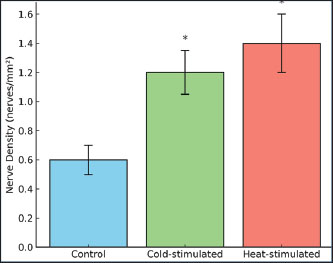

Fig. 4. Expression of temperature receptors (TRPM8 and TRPV1) and histone modification genetic markers in the dorsal tail skin of BALB/c mice. Both cold and heat stimulation led to epigenetic changes in the hypothalamic neurons. Histone acetylation levels increased, with higher H3K27ac levels detected in both groups. This marker indicates transcriptional activation. H3K9me3, associated with gene repression, was reduced (Fig. 4B). Changes in nerve density after cold and heat stimulationQuantification of NFs showed clear changes after exposure to both cold and heat. Cold stimulation increased the TRPM8-positive nerve density from 0.6 to approximately 1.2 nerves/mm². Heat stimulation also increased the nerve density, reaching approximately 1.4 nerves/mm² for TRPV1-positive fibers. The diameter of NFs increased significantly in both cases (Fig. 5).

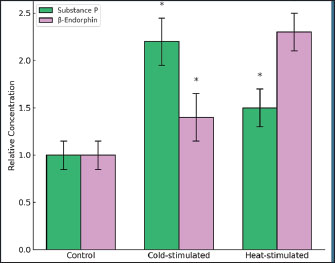

Fig. 5. Nerve density in mouse tail skin illustrating the relative density of NFs in the dorsal tail skin of BALB/c mice. Neuropeptide levels following cold or heat stimulationSubstance P and β-Endorphin showed significant increases (p < 0.05) in both stimulated groups compared with the baseline levels of both peptides (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6. Analysis of neuropeptides showing the relative concentrations of substance P and β-Endorphin in tail skin tissue of BALB/c mice. Neuropeptide levels were measured using HPLC. DiscussionThe hypothalamus integrates various sensory inputs to maintain body homeostasis. Its complex network of nuclei regulates not only thermoregulation but also endocrine, metabolic, and behavioral functions (Langlois et al., 2022). The observed histological changes in mouse tail skin highlight how peripheral sensory inputs activate these central hypothalamic circuits. The increased expression of TRPM8 and TRPV1 after cold and heat stimulation, respectively, reflects the dynamic responsiveness of cutaneous thermoreceptors (Panula, 2021). Aging influences hormonal sensitivity and receptor activity, potentially altering these thermosensory pathways as animals mature (Hill et al., 2020). Thermal stimulation induces measurable changes in peripheral nerve density in the mouse tail. Cold exposure significantly increased TRPM8-positive NFs, whereas heat exposure enhanced TRPV1-related nerve profiles. These structural alterations included nerve number and diameter expansion, indicating adaptive remodeling of the cutaneous sensory network. The sensory system responds to repeated environmental stimuli by reinforcing its structural presence. This remodeling supports the hypothesis that thermal cues enhance peripheral sensitivity. Increased nerve density may intensify sensory signal transmission toward central structures, facilitating rapid temperature regulation (Winter et al., 2017). Strong transcriptional responses supported these anatomical changes. TRPM8 mRNA expression increased sharply after cold stimulation, while TRPV1 mRNA increased after heat exposure. These fold changes were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method, confirming significant transcriptional upregulation. This pattern mirrors the findings on nerve density and confirms that receptor gene activity is tightly linked with local neuronal expansion. These results demonstrate that cold and heat activate specific transcriptional programs in thermosensory neurons. We interpret this coordinated structural and genetic response as an integrated adaptation mechanism. It strengthens the receptor system against future thermal stress, helping the organism maintain homeostasis (AlGonzález-Montelongo et al., 2016; Reimúndez et al., 2018). Thermal stimulation also induced epigenetic changes in the hypothalamic regions at the molecular level. Both cold and heat treatment significantly elevated H3K27ac levels and suppressed H3K9me3 expression. These changes demonstrate that chromatin relaxation and transcriptional activation occur in the central sensory processing centers. The hypothalamus, which is known for its regulatory role in temperature and homeostasis, appears to undergo dynamic remodeling in response to peripheral stimulation. This confirms previous hypothalamic models that adjust their structure and function to external demands (Alatzoglou et al., 2020; Cheon et al., 2025). These histone changes may serve as early regulatory mechanisms, preparing neurons for enhanced sensory processing-related gene transcription. Neuropeptide analysis provided further evidence of the central involvement of the tumor. Substance P and β-Endorphin levels increased significantly after thermal exposure. Cold stimulation led to the strongest increase in Substance P, while β-Endorphin was more elevated in the heat group. These findings support the notion that both cold and heat influence neurochemical output. Elevated neuropeptide levels confirm that thermal stimulation affects not only local sensory pathways but also brain circuits responsible for peptide release. The hypothalamus and pituitary are likely involved in coordinating these responses. Similar peptide shifts occur in stress-related conditions such as ectopic Cushing’s syndrome (Ragnarsson et al., 2024), where ACTH levels alter downstream hormonal systems. Although CRH and ACTH were not measured in this study, earlier models suggest that thermal cues could indirectly influence these axes. Kisspeptin is one such example; it links energy balance and reproductive signaling (Navarro, 2020). The observed peptide changes may reflect a wider neuroendocrine response, possibly involving pathways beyond thermoregulation. The hypothalamus, especially paraventricular and lateral zones, modulates respiratory and autonomic functions in response to sensory input (Fukushi et al., 2019). Microglial activity in these zones can also affect synaptic reorganization, thereby influencing both sensory and hormonal responses (Fang et al., 2023). The findings of this study support the hypothesis that thermal stimuli activate a broad set of sensory and regulatory pathways that help the brain adapt to environmental changes. Such pathways may be targeted in the future through pharmacological tools, such as agents that affect the release of growth hormones (Sigalos and Pastuszak, 2018). ConclusionThis study confirmed that TRPM8 and TRPV1 respond strongly to cold and heat in the tail skin of mice with BALB/c. Both histological and molecular analyses revealed clear nerve activation and gene changes. AcknowledgmentThe authors thank the College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Al-Qadisiyah, for their support in this study. Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest. FundingThe authors self-funded the study. No external funding source is available. Authors’ contributionsAll authors participated in the study. Data availabilityData are available when requested by the corresponding author. ReferencesAdamantidis, A.R. and De Lecea, L. 2023. Sleep and the hypothalamus. Science 382(6669), 405–412; doi:10.1126/science.adh8285 Alatzoglou, K.S., Gregory, L.C. and Dattani, M.T. 2020. Development of the pituitary gland. Compreh. Physiol. 10(2), 389–413; doi:10.1002/cphy.c150043 Andrè, E., Campi, B., Materazzi, S., Trevisani, M., Amadesi, S., Massi, D., Creminon, C., Vaksman, N., Nassini, R., Civelli, M., Baraldi, P.G., Poole, D.P., Bunnett, N.W., Geppetti, P. and Patacchini, R. 2008. Cigarette smoke–induced neurogenic inflammation is mediated by α,β-unsaturated aldehydes and the TRPA1 receptor in rodents. J. Clin. Invest. 118(7), 2574–2582; doi:10.1172/JCI34886 Asa, S.L., Mete, O., Perry, A. and Osamura, R.Y. 2022. Overview of the 2022 WHO classification of pituitary tumors. Endocrine Pathol. 33(1), 6–26; doi:10.1007/s12022-022-09703-7 Caterina, M.J., Leffler, A., Malmberg, A.B., Martin, W.J., Trafton, J., Petersen-Zeitz, K.R., Koltzenburg, M., Basbaum, A.I. and Julius, D. 2000. Impaired nociception and pain sensation in mice lacking the capsaicin receptor. Science 288(5464), 306–313; doi:10.1126/science.288.5464.306 Chapman, P.R., Singhal, A., Gaddamanugu, S. and Prattipati, V. 2020. Neuroimaging of the pituitary gland: practical anatomy and pathology. Radiol. Clin. North Amer. 58(6), 1115–1133; doi:10.1016/j.rcl.2020.07.009 Cheon, D.H., Park, S., Park, J., Koo, M., Kim, H.H., Han, S. and Choi, H.J. 2025. Lateral hypothalamus and eating: cell types, molecular identity, anatomy, temporal dynamics and functional roles. Exp. Mol. Med. 57(5), 925–937; doi:10.1038/s12276-025-01451-y Christ-Crain, M., Bichet, D.G., Fenske, W.K., Goldman, M.B., Rittig, S., Verbalis, J.G. and Verkman, A.S. 2019. Diabetes insipidus. Nature Rev. Dis. Primers 5(1), 54; doi:10.1038/s41572-019-0103-2 Dudás, B. 2021. Anatomy and cytoarchitectonics of the human hypothalamus. Handbook Clin. Neurol. 179, 45–66; doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-819975-6.00001-7 Fang, S., Wu, Z., Guo, Y., Zhu, W., Wan, C., Yuan, N., Chen, J., Hao, W., Mo, X., Guo, X., Fan, L., Li, X. and Chen, J. 2023. Roles of microglia in adult hippocampal neurogenesis in depression and their therapeutics. Front. Immunol. 14, 1193053; doi:10.3389/fimmu.2023.1193053 Feldt-Rasmussen, U., Effraimidis, G. and Klose, M. 2021. The hypothalamus-pituitary-thyroid (HPT)-axis and its role in physiology and pathophysiology of other hypothalamus-pituitary functions. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 525, 111173; doi:10.1016/j.mce.2021.111173 Fong, H., Zheng, J. and Kurrasch, D. 2023. The structural and functional complexity of the integrative hypothalamus. Science 382(6669), 388–394; doi:10.1126/science.adh8488 Fukushi, I., Yokota, S. and Okada, Y. 2019. The role of the hypothalamus in modulation of respiration. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 265, 172–179; doi:10.1016/j.resp.2018.07.003 González-Montelongo, R., Barros, F., Alvarez de la Rosa, D. and Giraldez, T. 2016. Plasma membrane insertion of epithelial sodium channels occurs with dual kinetics. Pflugers Archiv : Eur. J. Physiol. 468(5), 859–870; doi: 10.1007/s00424-016-1799-4 Hill, M., Třískala, Z., Honců, P., Krejčí, M., Kajzar, J., Bičíková, M., Ondřejíková, L., Jandová, D. and Sterzl, I. 2020. Aging, hormones and receptors. Physiol. Res. 69(Suppl 2), S255–S272; doi:10.33549/physiolres.934523 Lakomá, J., Rimondini, R., Ferrer Montiel, A., Donadio, V., Liguori, R. and Caprini, M. 2016. Increased expression of TRPV1 in peripheral terminals mediates thermal nociception in Fabry disease mouse model. Mol. Pain 12, V1–11; doi:10.1177/1744806916661069 Langlois, F., Varlamov, E.V. and Fleseriu, M. 2022. Hypophysitis, the growing spectrum of a rare pituitary disease. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 107(1), 10–28; doi:10.1210/clinem/dgab672 Livak, K.J. and Schmittgen, T.D. 2001. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT Method. Methods 25(4), 402–408; doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262 Lu, W., Li, X. and Luo, Y. 2021. FGF21 in obesity and cancer: new insights. Cancer Lett. 499, 5–13; doi:10.1016/j.canlet.2020.11.026 Maita, I., Bazer, A., Blackford, J.U. and Samuels, B.A. 2021. Functional anatomy of the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis-hypothalamus neural circuitry: implications for valence surveillance, addiction, feeding, and social behaviors. Handbook Clin. Neurol. 179, 403–418; doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-819975-6.00026-1 May, A., Schwedt, T.J., Magis, D., Pozo-Rosich, P., Evers, S. and Wang, S.J. 2018. Cluster headache. Nature Rev. Dis. Primers 4, 18006; doi:10.1038/nrdp.2018.6 Mckemy, D.D., Neuhausser, W.M. and Julius, D. 2002. Identification of a cold receptor reveals a general role for TRP channels in thermosensation. Nature 416(6876), 52–58; doi:10.1038/nature719 Nagpal, J., Herget, U., Choi, M.K. and Ryu, S. 2019. Anatomy, development, and plasticity of the neurosecretory hypothalamus in zebrafish. Cell Tissue Res. 375(1), 5–22; doi:10.1007/s00441-018-2900-4 Navarro, V.M. 2020. Metabolic regulation of kisspeptin: the link between energy balance and reproduction. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 16(8), 407–420; doi:10.1038/s41574-020-0363-7 Panula, P. 2021. Histamine receptors, agonists, and antagonists in health and disease. Handbook Clin. Neurol. 180, 377–387; doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-820107-7.00023-9 Ragnarsson, O., Juhlin, C.C., Torpy, D.J. and Falhammar, H. 2024. A clinical perspective on ectopic Cushing's syndrome. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 35(4), 347–360; doi:10.1016/j.tem.2023.12.003 Reimúndez, A., Fernández-Peña, C., García, G., Fernández, R., Ordás, P., Gallego, R., Pardo-Vazquez, J.L., Arce, V., Viana, F. and Señarís, R. 2018. Deletion of the cold thermoreceptor TRPM8 increases heat loss and food intake leading to reduced body temperature and obesity in mice. J. Neurosci. 38(15), 3643–3656; doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3002-17.2018 Richards, J.S. 2018. The ovarian cycle. Vitamins Hormones 107, 1–25; doi:10.1016/bs.vh.2018.01.009 Sigalos, J.T. and Pastuszak, A.W. 2018. The safety and efficacy of growth hormone secretagogues. Sexual Med. Rev. 6(1), 45–53; doi:10.1016/j.sxmr.2017.02.004 Song, J. and Choi, S.Y. 2023. Arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus: anatomy, physiology, and diseases. Exp. Neurobiol. 32(6), 371–386; doi:10.5607/en23040 Vivier, E., Artis, D., Colonna, M., Diefenbach, A., Di Santo, J.P., Eberl, G., Koyasu, S., Locksley, R.M., Mckenzie, A.N.J., Mebius, R.E., Powrie, F. and Spits, H. 2018. Innate lymphoid cells: 10 years on. Cell 174(5), 1054–1066; doi:10.1016/j.cell.2018.07.017 Winter, Z., Gruschwitz, P., Eger, S., Touska, F. and Zimmermann, K. 2017. Cold temperature encoding by cutaneous TRPA1 and TRPM8-bearing fibers in the mouse. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 10, 209; doi:10.3389/fnmol.2017.00209 | ||

| How to Cite this Article |

| Pubmed Style Nuha Shaker Ali. Histological evaluation of thermosensory receptors and cutaneous neurovascular in the tail skin of BALB/c mice. Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(9): 4128-4135. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i9.18 Web Style Nuha Shaker Ali. Histological evaluation of thermosensory receptors and cutaneous neurovascular in the tail skin of BALB/c mice. https://www.openveterinaryjournal.com/?mno=265231 [Access: January 25, 2026]. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i9.18 AMA (American Medical Association) Style Nuha Shaker Ali. Histological evaluation of thermosensory receptors and cutaneous neurovascular in the tail skin of BALB/c mice. Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(9): 4128-4135. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i9.18 Vancouver/ICMJE Style Nuha Shaker Ali. Histological evaluation of thermosensory receptors and cutaneous neurovascular in the tail skin of BALB/c mice. Open Vet. J.. (2025), [cited January 25, 2026]; 15(9): 4128-4135. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i9.18 Harvard Style Nuha Shaker Ali (2025) Histological evaluation of thermosensory receptors and cutaneous neurovascular in the tail skin of BALB/c mice. Open Vet. J., 15 (9), 4128-4135. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i9.18 Turabian Style Nuha Shaker Ali. 2025. Histological evaluation of thermosensory receptors and cutaneous neurovascular in the tail skin of BALB/c mice. Open Veterinary Journal, 15 (9), 4128-4135. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i9.18 Chicago Style Nuha Shaker Ali. "Histological evaluation of thermosensory receptors and cutaneous neurovascular in the tail skin of BALB/c mice." Open Veterinary Journal 15 (2025), 4128-4135. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i9.18 MLA (The Modern Language Association) Style Nuha Shaker Ali. "Histological evaluation of thermosensory receptors and cutaneous neurovascular in the tail skin of BALB/c mice." Open Veterinary Journal 15.9 (2025), 4128-4135. Print. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i9.18 APA (American Psychological Association) Style Nuha Shaker Ali (2025) Histological evaluation of thermosensory receptors and cutaneous neurovascular in the tail skin of BALB/c mice. Open Veterinary Journal, 15 (9), 4128-4135. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i9.18 |