| Research Article | ||

Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(9): 4114-4120 Open Veterinary Journal, (2025), Vol. 15(9): 4114-4120 Research Article Anatomical investigation of cutaneous plantar mechanoreceptor pathways and their connections to hypothalamic structures in laboratory ratsSaffia Kareem Wally Alumeri, Maha Abdul-Hadi Abdul-Rida Al-Abdula* and Salim Salih Ali Al-KhakaniDepartment of Anatomy and Histology, College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Al-Qadisiyah, Al-Diwaniyah City, Iraq *Corresponding Author: Maha Abdul-Hadi Abdul-Rida Al-Abdula. Department of Anatomy and Histology, College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Al-Qadisiyah, Al-Diwaniyah City, Iraq. Email: maha.alabdula [at] qu.edu.iq Submitted: 17/06/2025 Revised: 03/08/2025 Accepted: 11/08/2025 Published: 30/09/2025 © 2025 Open Veterinary Journal

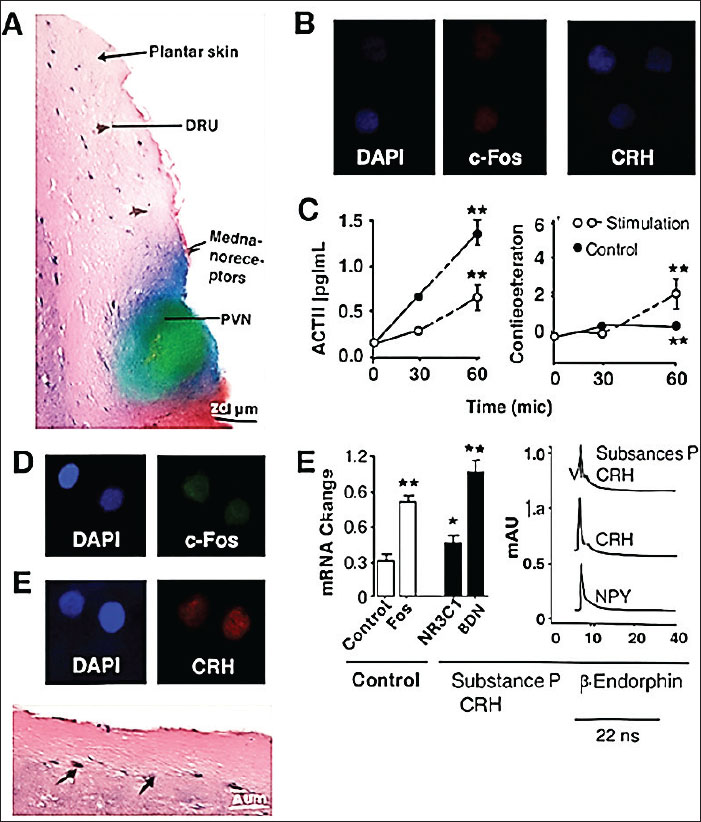

ABSTRACTBackground: Cutaneous mechanoreceptors detect physical stimuli. Their pathways to the CNS are not fully mapped. Understanding these connections helps explain the sensory regulation of endocrine function. Aim: This study mapped the anatomical connections between plantar skin mechanoreceptors and hypothalamic nuclei. The structural, cellular, and neurochemical features were examined. Methods: A total of 24 male Wistar rats were used. The plantar skin was stimulated with calibrated vibration. Tissue samples were collected from the skin, spinal cord, and hypothalamus. We used Fast Blue and BDA as tract tracers to map the neural connections. Immunofluorescence was performed to label c-Fos, corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), calcitonin Gene-related peptide, and substance P. Confocal microscopy was used to visualize labeled pathways. We measured ACTH and corticosterone levels using hormonal assays. ChIP-qPCR was performed to detect changes in histone modifications. The gene expression of CRH, Fos, Arginine Vasopressin (AVP), NR3C1, and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) was measured by reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR). High-performance liquid chromatography was used to identify neuropeptide concentrations. Results: Tracer analysis revealed direct afferent projections from the plantar skin to the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus (of the hypothalamus). Immunofluorescence analysis showed strong c-Fos and CRH expression in stimulated animals. Serum adrenocorticotropic hormone and corticosterone levels increased after stimulation. Histone acetylation (H3K27ac) was elevated in hypothalamic neurons. RT-qPCR showed increased CRH, Fos, AVP, NR3C1, and BDNF expression. High-performance liquid chromatography confirmed elevated CRH, substance P, Neuropeptide Y, and β-endorphin levels after stimulation. Conclusion: Plantar skin mechanoreceptors directly connect to the hypothalamic regions. Mechanical stimulation activates the neuroendocrine response. This pathway integrates cutaneous sensation and hormonal regulation. Keywords: ACTH, Anatomy, Corticosterone, Hypothalamus, Mechanoreceptors. IntroductionThe pituitary gland plays a central role in the regulation of endocrine functions. Pituitary incidentalomas are common imaging findings (Giraldi et al., 2023). These lesions may remain silent or cause hormonal disturbances. Some pituitary masses lead to excessive adenosine triphosphate (ACTH) secretion, resulting in Cushing’s disease. Ectopic ACTH production also occurs, which contributes to ectopic Cushing’s syndrome (Ragnarsson et al., 2024). In such cases, tumors outside the pituitary gland produce ACTH. Neuroendocrine neoplasms, including bronchial carcinoids and small cell lung cancers, are frequent sources of ectopic ACTH (Ragnarsson et al., 2024). Proopiomelanocortin synthesis in corticotroph cells is the primary source of ACTH (Hasenmajer et al., 2021). These cells mainly reside in the anterior pituitary. ACTH binds melanocortin receptors on adrenal glands to stimulate cortisol production (Hasenmajer et al., 2021). The melanocortin system also includes alpha-, beta-, and gamma-MSH hormones (Wang et al., 2019). These peptides regulate inflammation and energy balance. Melanocortin receptors are distributed across different tissues, highlighting the effects of ACTH (Wang et al., 2019). The hypothalamus integrates sensory and hormonal signals. High ACE2 expression is found in hypothalamic regions such as the paraventricular nucleus (Ong et al., 2022). This region regulates fluid balance and responds to osmotic changes. The paraventricular nucleus (of the hypothalamus) (PVN) plays a critical role in coordinating the endocrine response to sensory input. Its involvement in neuroendocrine reflexes makes it essential for the regulation of ACTH. Drugs that target pituitary adenomas include cabergoline and pasireotide (Gadelha et al., 2022). These medications help control the secretion of hormones in Cushing’s disease. Pituitary tumors often respond to these agents, thereby reducing the ACTH output. However, some tumors require surgical intervention or radiotherapy. Tumor-directed therapies continue to evolve, providing new treatment options (Theodoropoulou and Reincke, 2019). Precision tumor pathway targeting improves outcomes. Innovative approaches focus on blocking tumor-specific receptors (Von Selzam and Theodoropoulou, 2022). These methods offer hope for patients with RD. The neuroendocrine system also influences other organs, such as the sebaceous glands. Hormonal changes affect sebum production (Clayton et al., 2020). Excess growth hormone, thyroxine, or prolactin levels increase sebaceous activity. In contrast, hormone deficiencies reduce sebum output. Adrenal insufficiency contributes to dry skin caused by cortisol deficiency. In adults, anterior pituitary dysfunction leads to multiple hormonal deficiencies (Prencipe et al., 2023). Patients experience fatigue, weakness, and metabolic disturbances. Hypopituitarism affects the quality of life and increases morbidity. Secondary adrenal insufficiency is caused by ACTH deficiency, which impairs cortisol synthesis. Central hypothyroidism reflects low thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) production, while hypogonadotropic hypogonadism reduces sex hormone levels. Deficits in growth hormone and prolactin further impact bodily functions (Prencipe et al., 2023). The interaction between sensory input and hormonal regulation is still under investigation. Studies mapping cutaneous mechanoreceptors reveal connections to the hypothalamic centers. These pathways suggest a direct link between peripheral sensation and Estrogen receptors. Mechanical stimulation may influence hypothalamic activity, altering the secretion of ACTH. These findings offer new insights into the integration of neuroendocrine systems. Further research can help explain the coordination between sensory nerves and hormonal output. Understanding these circuits supports better management of EDs. It also opens opportunities for novel therapies targeting neural pathways to modulate hormonal release. This study mapped the anatomical connections between plantar skin mechanoreceptors and hypothalamic nuclei. The structural, cellular, and neurochemical features were examined. Materials and MethodsAnimalsTwenty-four adult male Wistar rats (weight, 200–250 g; 10–12 weeks old) were used. Rats were purchased from the local Lab Animal Center in Al-Diwaniyah, Iraq. Animals were maintained under standard laboratory conditions. The rats were housed in plastic cages with bedding and maintained at 22°C ± 2°C. Relative humidity was maintained at 55%–60%. A 12-hour light/dark cycle was used. Food and clean water were provided ad libitum. The temperature was 22°C ± 2°C. The light/dark cycle was 12 hours. Food and water were provided ad libitum. Experimental groupsRats were divided into three groups: Group A (control, n=8), Group B (mechanical stimulation, n=8), and Group C (stimulation with lidocaine nerve block, n=8) Mechanical stimulationA piezoelectric footpad stimulator delivered 100 Hz vibration for 5 minutes daily for three consecutive days. The stimulator was placed under the right footpad. Group C received 2% subcutaneous lidocaine injections before stimulation. Tract tracingFast Blue (2%, 0.5 µl) was injected into the PVN. BDA (10%, 0.5 µl) was injected into the plantar dermis. The injections were performed using a stereotaxic frame. After 72 hours, the tissues were collected for analysis. Tissue collectionAfter stimulation, the rats were anesthetized with ketamine (100 mg/kg, Cat# K2753, Sigma-Aldrich) and xylazine (10 mg/kg, Cat# X1251) and perfused with 4% paraformaldehyde. The plantar skin, spinal cord (L4-L6), hypothalamus, and pituitary were harvested. Tissues were fixed in paraformaldehyde overnight. HistologyThe samples were processed for paraffin embedding. They were dehydrated in ethanol, cleared in xylene, and embedded in paraffin blocks. Sections (5 µm thick) were cut using a rotary microtome (Leica RM2125RTS). Slides were stained with Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E). ImmunofluorescenceCryosections were used for confocal microscopy. Primary antibodies included: c-Fos (Abcam # ab190289), corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) (Santa Cruz Cat#sc-1759), calcitonin gene-related peptide (Sigma-Aldrich #C7113), and substance P (Abcam Cat# ab10353). Alexa Fluor-conjugated secondary antibodies were used (Invitrogen Cat # A-11008, A-11001, A-11055). Confocal imagingImages were acquired using a confocal microscope (LSM 880, Zeiss). Z-stack images were analyzed using the Fiji/ImageJ software. Morphometric analysis of receptor density was performed. Hormonal assaysBlood samples were collected at 0, 30, and 60 minutes after the final stimulation. ACTH was measured using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit (MyBioSource, Cat# MBS701581). Corticosterone was measured using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit (Arbor Assays, Cat# K014-H1). All samples and standards were added to wells precoated with specific antibodies. Plates were incubated with the detection reagent. After washing, absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader. The concentrations were calculated from the standard curves. RNA extraction and Reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)Total RNA was extracted using the TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). cDNA was synthesized using a High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems). RT-qPCR was performed using SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) on a QuantStudio 5 system. CRH F: CCTCAGCCGGTTCTGATCC R: GCGGAAAAAGTTAGCCGCAG (NM_205769), Fos: F: CGGGTTTCAACGCCGACTA R: TGGCACTAG AGACGGACAGAT (NM_010234), Arginine Vasopressin: F: ATGCTCAACACTACGCTCTCC R: CTTGGCAGAATCCACGGACT (NM_009732), NR3C1: F: GACTCCAAAGAATCCTTAGCTCC R: CTCCACCCCTCAGGGTTTTAT (NM_008173), BDNF: F: TCATACTTCGGTTGCATGAAGG R: ACACCTGGGTAGGCCAAGTT (NM_001048141), and β-Actin: F: GTGACGTTGACATCCGTAAAGA R: GCCGGACTCATCGTACTCC (NM_007393). RNA quality was checked using the NanoDrop. cDNA was synthesized using the High-Capacity cDNA Kit (Applied Biosystems, Cat# 4368814). RT-qPCR was performed using SYBR Green Master Mix (Cat# 4309155) on a QuantStudio 5. Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP-qPCR)The hypothalamic and pituitary nuclei were isolated. ChIP was performed using the SimpleChIP Kit (Cell Signaling Technology, Cat# 9003). The antibodies used were H3K27ac (CST, Cat# 8173) and H3K9me3 (CST, Cat# 13969). After immunoprecipitation, DNA was purified and analyzed by qPCR using primers for the CRH promoter. High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysisFor HPLC analysis, hypothalamic tissues were homogenized in a cold buffer. Extracts were filtered and analyzed using an Agilent 1260 Infinity II HPLC system. A ZORBAX Eclipse Plus C18 column (4.6 × 150 mm) was used to separate the peptides. Detection was performed at 214 nm. The measured peptides included CRH, substance P, Neuropeptide Y (NPY), and β-endorphin. Statistical analysisData were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 10. ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test was performed. Significance was set at p < 0.05. Ethical approvalThe study was approved by the Institutional Animal Ethics Committee (1162 on 22/02/2024). ResultsIdentified neural connectionsThe evidence is shown in Figure 1. Figure 1A displays Fast Blue and BDA labeling in the PVN, confirming projections from plantar skin mechanoreceptors. The DRU and PVN structures are clearly visible with strong fluorescence signals. The colored overlay marks the afferent pathways reaching the hypothalamus. Silver staining confirms the arrangement of nerve fibers, while the H&E image shows nerve bundles in the dermis with arrows pointing to mechanoreceptor fields near the epidermis. Figure 1B shows c-Fos and CRH labeling in PVNs after stimulation. Figure 1D and E confirms the co-expression of these markers in the activated group. The bar graphs in Figure 1F present quantitative evidence, showing a sharp increase in labeled cells compared with controls, which showed minimal staining. Negative control sections were run without primary antibodies. No signal was detected in the control group.

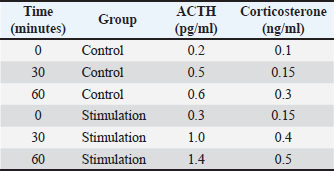

Fig. 1. Anatomical connections between plantar cutaneous mechanoreceptors and hypothalamic activity in laboratory rats. A: 3D tract tracing map showing afferent projections from the plantar skin to the paraventricular nucleus (PVN). DRU: dorsal root units; Fast Blue and BDA labeling: mechanoreceptors indicated by arrows. B: Confocal immunofluorescence images of PVN neurons. Nuclear c-Fos (red) and cytoplasmic CRH (green) after stimulation. C: Hormonal time-course graphs. Left: ACTH levels (pg/ml). Right: corticosterone levels (ng/ml). Stimulation significantly increased hormone secretion compared to controls. D: Additional PVN immunofluorescence showing strong nuclear c-Fos and cytoplasmic CRH signals in stimulated animals. E: Gene expression bar chart. mRNA changes for Control, Fos, NR3C1, and BDNF with 45°-rotated labels. E: High-performance liquid chromatography chromatograms of neuropeptides showing increased peaks for Substance P, CRH, and NPY after stimulation. Lower image: H&E-stained plantar skin section showing nerve bundles (arrows) near the DE junction. Endocrine activation after stimulationHormonal measurements showed increased adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) and corticosterone levels after plantar stimulation. Figure 1C presents the time course of hormonal changes. ACTH increased from 0.3 to 1.4 pg/ml within 60 minutes. Corticosterone level increased from 0.15 to 0.5 ng/ml over the same period. The control animals displayed small increases. The results showed a significant increase in hormone levels in the stimulation group at 30 and 60 minutes (p=0.001) compared with the control group (Table 1). Table 1. Hormonal time course. Time indicates minutes after stimulation. The ACTH and corticosterone values are presented as means. “Stimulation”=Group B.

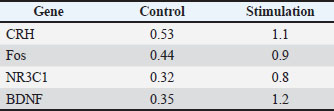

Gene expression analysis is displayed in Figure 1E (left bar chart). After stimulation, CRH, Fos, NR3C1, and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) expression increased significantly. Fold changes ranged between 2 and 4 compared with controls. CRH expression was doubled relative to baseline. Histone modification analysis indicated chromatin remodeling. Increased gene expression was correlated with activated transcriptional activity. H3K27ac was upregulated, and H3K9me3 was decreased after stimulation, although specific quantification was not performed (Table 2). Table 2. Changes in gene expression. Gene expression levels are the fold-change values from RT-qPCR.

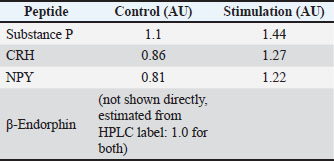

Changes in neuropeptides after stimulationHPLC results confirmed the presence of elevated neuropeptides. Figure 1E (right chromatogram) shows the larger peak areas for CRH, substance P, and NPY. Substance P increased from 1.0 to 1.4 AU, CRH increased from 0.9 to 1.3 AU, and NPY increased from 0.8 to 1.2 AU. β-endorphin was indicated as baseline. Elevated neuropeptide levels matched with prior immunofluorescence findings. The PVN neurons showed stronger CRH labeling after stimulation. The integration of molecular, biochemical, and imaging data supported a complete sensory-endocrine circuit. The lidocaine group prevented most of these changes. This confirmed that the neuroendocrine responses were dependent on the activation of the intact sensory nerve (Table 3 and Fig. 1). Table 3. Neuropeptide levels. Neuropeptide levels (AU=arbitrary units) determined by HPLC.

DiscussionCushing’s disease remains one of the most complex endocrine disorders due to its varied causes and mechanisms. In pediatric populations, pituitary corticotroph adenomas significantly contribute to ACTH hypersecretion, although their incidence is much lower than that in adults (Savage and Ferrigno, 2024). These adenomas lead to excess cortisol production, highlighting the central role of ACTH in disease development. The glucocorticoid receptor also plays a regulatory role in corticotroph adenomas by mediating cortisol feedback. However, mutations or impaired receptor function may diminish this negative feedback loop, causing persistent ACTH secretion (Regazzo et al., 2022). Increased hormonal activity often leads to long-term metabolic and psychological consequences in patients with alopecia. Additionally, recent findings have noted that pituitary dysfunction occurs after COVID-19 vaccinations, with cases reporting hypophysitis, pituitary apoplexy, and isolated ACTH deficiencies (Verrienti et al., 2024). This further supports the sensitivity of the pituitary gland to both endogenous and exogenous insults that affect ACTH regulation. The spectrum of ACTH-secreting tumors is broader than initially thought. Metastatic pituitary tumors often involve ACTH-producing subtypes, complicating both diagnosis and management (Yearley et al., 2023). Radiosurgery remains a therapeutic option, especially for patients who are not ideal candidates for conventional surgery, although outcomes vary depending on tumor responsiveness (Losa et al., 2022). Corticotroph tumors themselves may behave unpredictably; some recur even after successful interventions, and their molecular underpinnings suggest diverse tumorigenic pathways including Tpit lineage abnormalities (Hinojosa-Amaya et al., 2021). Rare cases of spontaneous remission in Cushing’s disease have also been documented, indicating that certain internal modulatory mechanisms may still override disease progression in select individuals (Popa Ilie et al., 2021). Trauma has also been implicated, where traumatic brain injury can lead to ACTH deficiency and related hormonal imbalances, adding another layer to the understanding of pituitary vulnerability (Tudor and Thompson, 2019). The pituitary gland exhibits plasticity across the lifespan, which may explain the observed variability in clinical courses. Resident pituitary stem cells likely contribute to its capacity for remodeling and regeneration in response to physiological demands (Laporte et al., 2021). Surgical intervention remains a primary treatment for many pituitary disorders, although tumor subtype and size heavily influence outcomes. Some patients experience recovery of pituitary function after transsphenoidal surgery, while others develop new hormone deficiencies (Mavromati et al., 2023). The behavior of silent corticotroph tumors adds further complexity, as these can present without overt hypercortisolemia but still harbor potential for malignancy (Vuong and Dunn, 2023). Advances in stem cell research have proposed the possibility of generating hormone-producing pituitary cells from PSCs, offering hope for future regenerative therapies (Suga, 2019). However, such approaches remain experimental and are not yet applicable in clinical settings. Rare ectopic ACTH-producing pituitary adenomas, sometimes misdiagnosed as chordoma, have also been described, further challenging diagnostic accuracy (Li et al., 2023). Among the more aggressive subtypes, compared with conventional corticotroph adenomas, crooke cell adenomas demonstrate poorer endocrinological outcomes and reduced remission rates after surgery (Findlay et al., 2023). Environmental and hormonal influences can also drive the formation of pituitary adenoma. For example, in both animal models and human cases, estrogen exposure has been shown to stimulate pituitary hyperplasia and adenoma development, particularly affecting lactotropic and growth hormone cells (Šošić-Jurjević et al., 2020). Collectively, these findings highlight the intricate control of pituitary ACTH secretion and the wide range of factors influencing the disease course. ConclusionThe present study extends this understanding by showing how mechanoreceptor activation in the skin may serve as an upstream modulator of hypothalamic-pituitary signaling, adding a novel dimension to the regulation of ACTH secretion through peripheral sensory pathways. AcknowledgmentThe authors thank the College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Al-Qadisiyah, for their support in this study. FundingThe authors self-funded the study. No external funding source is available. Authors’ contributionsAll authors participated in the study. Conflict of interestThe authors declare that there is no conflict of interest. Data availabilityData are available when requested by the corresponding author. ReferencesClayton, R.W., Langan, E.A., Ansell, D.M., De Vos, I.J.H.M., Göbel, K., Schneider, M.R., Picardo, M., Lim, X., Van Steensel, M.A.M. and Paus, R. 2020. Neuroendocrinology and neurobiology of sebaceous glands. Biol. Rev. Cambridge Phil. Soc. 95(3), 592–624; doi:10.1111/brv.12579 Findlay, M.C., Drexler, R., Azab, M., Karbe, A., Rotermund, R., Ricklefs, F.L., Flitsch, J., Smith, T.R., Kilgallon, J.L., Honegger, J., Nasi-Kordhishti, I., Gardner, P.A., Gersey, Z.C., Abdallah, H.M., Jane, J.A., Marino, A.C., Knappe, U.J., Uksul, N., Rzaev, J.A., Bervitskiy, A.V., Schroeder, H.W.S., Eördögh, M., Losa, M., Mortini, P., Gerlach, R., Antunes, A.C.M., Couldwell, W.T., Budohoski, K.P., Rennert, R.C. and Karsy, M. 2023. Crooke Ccell aAdenoma cConfers pPoorer eEndocrinological oOutcomes cCompared with cCorticotroph aAdenoma: results of a mMulticenter, iInternational aAnalysis. World Neurosurg. 180, e376–e391; doi:10.1016/j.wneu.2023.09.076 Gadelha, M.R., Wildemberg, L.E. and Shimon, I. 2022. Pituitary acting drugs: cabergoline and pasireotide. Pituitary 25(5), 722–725; doi:10.1007/s11102-022-01238-8 Giraldi, E., Allen, J.W. and Ioachimescu, A.G. 2023. Pituitary iIncidentalomas: best pPractices and lLooking aAhead. Endocr. Pract. 29(1), 60–68; doi:10.1016/j.eprac.2022.10.004 Hasenmajer, V., Bonaventura, I., Minnetti, M., Sada, V., Sbardella, E. and Isidori, A.M. 2021. Non-cCanonical eEffects of ACTH: insights iInto aAdrenal iInsufficiency. Front. Endocrinol. 12, 701263; doi:10.3389/fendo.2021.701263 Hinojosa-Amaya, J.M., Lam-Chung, C.E. and Cuevas-Ramos, D. 2021. Recent uUnderstanding and fFuture dDirections of rRecurrent cCorticotroph tTumors. Front. Endocrinol. 12, 657382; doi:10.3389/fendo.2021.657382 Laporte, E., Vennekens, A. and Vankelecom, H. 2021. Pituitary rRemodeling tThroughout lLife: are rResident sStem cCells iInvolved?. Front. Endocrinol. 11, 604519; doi:10.3389/fendo.2020.604519 Li, Y., Zhu, J.G., Li, Q.Q., Zhu, X.J. and Tian, J.H. 2023. Ectopic invasive ACTH-secreting pituitary adenoma mimicking chordoma: a case report and literature review. BMC Neurol. 23(1), 81; doi:10.1186/s12883-023-03124-7 Losa, M., Albano, L., Bailo, M., Barzaghi, L.R. and Mortini, P. 2022. Role of radiosurgery in the treatment of Cushing’s disease. J. Neuroendocrinol. 34(8), 13134; doi:10.1111/jne.13134 Mavromati, M., Mavrakanas, T., Jornayvaz, F.R., Schaller, K., Fitsiori, A., Vargas, M.I., Lobrinus, J.A., Merkler, D., Egervari, K., Philippe, J., Leboulleux, S. and Momjian, S. 2023. The impact of transsphenoidal surgery on pituitary function in patients with non-functioning macroadenomas. Endocrine 81(2), 340–348; doi:10.1007/s12020-023-03400-z Ong, W.Y., Satish, R.L. and Herr, D.R. 2022. ACE2, circumventricular organs and the hypothalamus, and COVID-19. Neuromolecular . Med. 24(4), 363–373; doi:10.1007/s12017-022-08706-1 Popa Ilie, I.R., Herdean, A.M., Herdean, A.I. and Georgescu, C.E. 2021. Spontaneous remission of Cushing’s disease: a systematic review. Ann. d’Endocrinol. 82(6), 613–621; doi:10.1016/j.ando.2021.10.002 Prencipe, N., Marinelli, L., Varaldo, E., Cuboni, D., Berton, A.M., Bioletto, F., Bona, C., Gasco, V. and Grottoli, S. 2023. Isolated anterior pituitary dysfunction in adulthood. Front. Endocrinology 14, 1100007; doi:10.3389/fendo.2023.1100007 Ragnarsson, O., Juhlin, C.C., Torpy, D.J. and Falhammar, H. 2024. A clinical perspective on ectopic Cushing’s syndrome. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 35(4), 347–360; doi:10.1016/j.tem.2023.12.003 Regazzo, D., Mondin, A., Scaroni, C., Occhi, G. and Barbot, M. 2022. The Role of gGlucocorticoid rReceptor in the pPathophysiology of pPituitary cCorticotroph aAdenomas. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23(12), 6469; doi:10.3390/ijms23126469 Savage, M.O. and Ferrigno, R. 2024. Paediatric Cushing’s disease: long-term outcome and predictors of recurrence. Front. Endocrinol. 15, 1345174; doi:10.3389/fendo.2024.1345174 Šošić-Jurjević, B., Ajdžanović, V., Miljić, D., Trifunović, S., Filipović, B., Stanković, S., Bolevich, S., Jakovljević, V. and Milošević, V. 2020. Pituitary hyperplasia, hormonal changes and prolactinoma development in males exposed to estrogens—An insight from translational studies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21(6), 2024; doi:10.3390/ijms21062024 Suga, H. 2019. Application of pluripotent stem cells for treatment of human neuroendocrine disorders. Cell Tissue Res. 375(1), 267–278; doi:10.1007/s00441-018-2880-4 Theodoropoulou, M. and Reincke, M. 2019. Tumor-directed therapeutic targets in cushing Ddisease. J. Clin. Endocrinol. &. Metab. 104(3), 925–933; doi:10.1210/jc.2018-02080 Tudor, R.M. and Thompson, C.J. 2019. Posterior pituitary dysfunction following traumatic brain injury: review. Pituitary 22(3), 296–304; doi:10.1007/s11102-018-0917-z Verrienti, M., Marino Picciola, V., Ambrosio, M.R. and Zatelli, M.C. 2024. Pituitary and COVID-19 vaccination: a systematic review. Pituitary 27(6), 970–985; doi:10.1007/s11102-024-01402-2 Von Selzam, V. and Theodoropoulou, M. 2022. Innovative tumour targeting therapeutics in Cushing’s disease. Best Pract. &. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. amp. Metab. 36(6), 101701; doi:10.1016/j.beem.2022.101701 Vuong, H.G. and Dunn, I.F. 2023. The clinicopathological features and prognosis of silent corticotroph tumors: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Endocrine 82(3), 527–535; doi:10.1007/s12020-023-03449-w Wang, W., Guo, D.Y., Lin, Y.J. and Tao, Y.X. 2019. Melanocortin regulation of inflammation. Front. Endocrinol. 10, 683; doi:10.3389/fendo.2019.00683 Yearley, A.G., Chalif, E.J., Gupta, S., Chalif, J.I., Bernstock, J.D., Nawabi, N., Arnaout, O., Smith, T.R., Reardon, D.A. and Laws, E.R. 2023. Metastatic pituitary tumors: an institutional case series. Pituitary 26(5), 561–572; doi:10.1007/s11102-023-01341-4 | ||

| How to Cite this Article |

| Pubmed Style Alumeri SKW, Al-abdula MAA, Al-khakani SSA. Anatomical investigation of cutaneous plantar mechanoreceptor pathways and their connections to hypothalamic structures in laboratory rats. Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(9): 4114-4120. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i9.16 Web Style Alumeri SKW, Al-abdula MAA, Al-khakani SSA. Anatomical investigation of cutaneous plantar mechanoreceptor pathways and their connections to hypothalamic structures in laboratory rats. https://www.openveterinaryjournal.com/?mno=265087 [Access: January 25, 2026]. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i9.16 AMA (American Medical Association) Style Alumeri SKW, Al-abdula MAA, Al-khakani SSA. Anatomical investigation of cutaneous plantar mechanoreceptor pathways and their connections to hypothalamic structures in laboratory rats. Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(9): 4114-4120. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i9.16 Vancouver/ICMJE Style Alumeri SKW, Al-abdula MAA, Al-khakani SSA. Anatomical investigation of cutaneous plantar mechanoreceptor pathways and their connections to hypothalamic structures in laboratory rats. Open Vet. J.. (2025), [cited January 25, 2026]; 15(9): 4114-4120. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i9.16 Harvard Style Alumeri, S. K. W., Al-abdula, . M. A. A. & Al-khakani, . S. S. A. (2025) Anatomical investigation of cutaneous plantar mechanoreceptor pathways and their connections to hypothalamic structures in laboratory rats. Open Vet. J., 15 (9), 4114-4120. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i9.16 Turabian Style Alumeri, Saffia Kareem Wally, Maha Abdul-hadi Abdul-rida Al-abdula, and Salim Salih Ali Al-khakani. 2025. Anatomical investigation of cutaneous plantar mechanoreceptor pathways and their connections to hypothalamic structures in laboratory rats. Open Veterinary Journal, 15 (9), 4114-4120. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i9.16 Chicago Style Alumeri, Saffia Kareem Wally, Maha Abdul-hadi Abdul-rida Al-abdula, and Salim Salih Ali Al-khakani. "Anatomical investigation of cutaneous plantar mechanoreceptor pathways and their connections to hypothalamic structures in laboratory rats." Open Veterinary Journal 15 (2025), 4114-4120. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i9.16 MLA (The Modern Language Association) Style Alumeri, Saffia Kareem Wally, Maha Abdul-hadi Abdul-rida Al-abdula, and Salim Salih Ali Al-khakani. "Anatomical investigation of cutaneous plantar mechanoreceptor pathways and their connections to hypothalamic structures in laboratory rats." Open Veterinary Journal 15.9 (2025), 4114-4120. Print. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i9.16 APA (American Psychological Association) Style Alumeri, S. K. W., Al-abdula, . M. A. A. & Al-khakani, . S. S. A. (2025) Anatomical investigation of cutaneous plantar mechanoreceptor pathways and their connections to hypothalamic structures in laboratory rats. Open Veterinary Journal, 15 (9), 4114-4120. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i9.16 |