| Research Article | ||

Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(8): 3618-3623 Open Veterinary Journal, (2025), Vol. 15(8): 3618-3623 Research Article Coronary dominance assessment in dogs: A comparative study of human and other speciesIván Andrés Pineda-Betancurt, Luis Ernesto Ballesteros-Acuña and Fabián Alejandro Gómez-Torres*Department of Basic Sciences, School of Medicine, Universidad Industrial de Santander, Bucaramanga, Colombia *Corresponding Author: Fabián Alejandro Gómez-Torres, Department of Basic Sciences, School of Medicine, Universidad Industrial de Santander, Bucaramanga, Colombia. Email: falegom [at] uis.edu.co Submitted: 07/06/2025 Revised: 20/07/2025 Accepted: 25/07/2025 Published: 31/08/2025 © 2025 Open Veterinary Journal

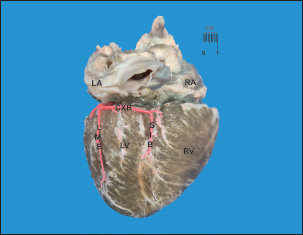

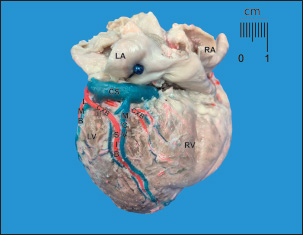

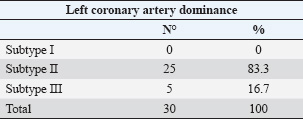

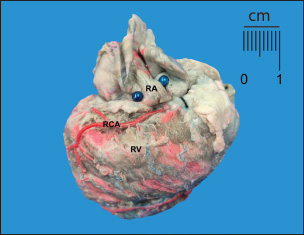

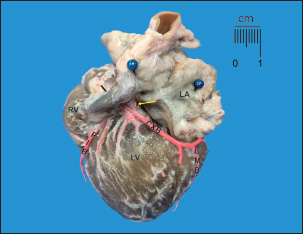

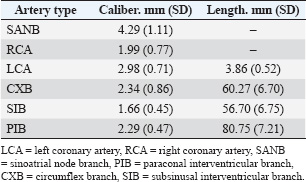

ABSTRACTBackground: Different animal species have been used in cardiological and interventional experiments. Detailed knowledge of coronary dominance in dogs can improve veterinary practice in this species. The right coronary artery is dominant in humans and pigs, while the left coronary artery is dominant in dogs and cattle. Aim: To provide a qualitative and biometric description of coronary dominance in dogs. Methods: The local ethics committee approved this study, and all samples were collected from veterinary clinics in Bucaramanga, Colombia. The coronary vasculature of the hearts of 30 dogs was perfused with semi-synthetic resin (80% Palatal GP40L and 20% styrene), and morphometric measurements were recorded. Results: A pattern of left coronary dominance was identified in the observed sample, with subtype II being the most prevalent in 25 (83.3%) hearts and subtype III in only 5 (16.7%) cases. The right coronary artery terminated between the right margin and the cardiac cross in 25 (83.3%) patients. The left coronary artery had a higher proximal caliber (2.98 ± 0.71 mm) than the right coronary artery (1.99 ± 0.77 mm) (p=0.001). The paraconal interventricular branch terminated in the posterior aspect of the left ventricle in 20 (66.7%) cases, and its proximal caliber was 2.29 ± 0.55 mm. The circumflex branch terminated in the subsinusal interventricular groove or cardiac cross in 23 (93.3%) patients, which is the main characteristic of left dominance. Conclusion: Our study enhances and classifies the concept of left coronary dominance in dogs by subtypes described in previous studies. This anatomical and biometric evaluation of coronary vessels optimizes the diagnosis, planning of cardiovascular procedures, and development of personalized clinical interventions in veterinary medicine. Keywords: Dogs, Coronary dominance, Left coronary artery, Circumflex branch, Subsinusal branch. IntroductionThe left coronary (LCA) and right coronary (RCA) arteries, which arise from the ascending aorta at its left and right ostia, respectively, supply the cardiac muscle. The concept of right or left coronary dominance is based on the trajectories and territories supplied by each branch and the perfusion of the ventricular diaphragmatic surface (Ballesteros Acuña et al., 2007). In humans and some animal species, coronary dominance is determined by the artery that gives rise to the posterior interventricular branch or subsinusal interventricular branch (SIB) in animals and the artery that mainly supplies the posterior wall of the left ventricle (LV) (Cavalcanti et al., 1995; Gómez et al., 2015). In humans, Schlesinger postulated that right dominance occurs when the RCA supplies the posterior surface of the right ventricle (RV) and gives rise to the posterior interventricular branch (SIB in animals), overriding the crux cordis to perfuse part of the LV. Left dominance occurred when the LCA supplied the posterior aspect of the LV, the posterior segment of the interventricular septum, and/or the posterior wall of the RV. Balanced dominance occurs when the RCA perfuses the RV and the posterior part of the interventricular septum via the posterior interventricular branch, together with the LCA that supplies the LV and terminates at the crux cordis (Schlesinger, 1940). Previous studies have consistently reported left dominance in dogs (Bertho and Gagnon, 1964; Noestelthaller et al., 2007; Oliveira et al., 2011), with the circumflex branch (CXB) running through the atrioventricular groove and giving rise to the SIB at the level of the cardiac crossover (Bertho and Gagnon, 1964; Oliveira et al., 2011; Auriemma et al., 2018). This expression of the dog coronary arteries differs from that of humans and pigs, where a predominance of right coronary dominance has been described (Ballesteros Acuña et al., 2007; Sahni et al., 2008); however, it is consistent with what has been reported in cattle, which showed a predominance of left coronary dominance (Gómez-Torres et al., 2023). Given the extensive nature of variability for this type of irrigation, DiDio and Wakefield presented a descriptive classification of left coronary dominance, with three subtypes: subtype I, where the RCA and LCA reach the crux cordis and end as parallel posterior interventricular branches; subtype II, where the LCA completely supplies the LV and septum, generating a single posterior interventricular branch from the CXB; subtype III, where all right posterior ventricular branches (including the posterior interventricular) emerge from the LCA supplying the interventricular septum, the LV, and part of the posterior wall of the RV (DiDio and Wakefield, 1975). It is of great clinical and procedural importance to understand the differences in coronary dominance among different species in detail. Left ventricular failure in dogs is caused by ischemia due to paraconal interventricular branch (PIB) occlusion (anterior interventricular in humans), leading to late-stage ventricular fibrillation, which accurately determines clinical heart failure due to coronary insufficiency (Wagner et al., 2009). This study determined the type of coronary dominance by injection of polyester resin. Along with the trajectories, branches, calibers, and lengths of the coronary vessels of the dog, the different weight ranges of the animals were evaluated. Materials and MethodsThis descriptive cross-sectional study was conducted on 30 hearts from dogs in veterinary clinics in Bucaramanga, Colombia, that died from natural causes. The analysis included dogs of different breeds, ages, and weights with no thoracic trauma and cardiac comorbidities. We use the current veterinary anatomical nomina list (World Association of Veterinary Anatomist, International Committee on Veterinary Gross Anatomical Nomenclature: Nomina Anatomica Veterinaria, 2017). The groups evaluated were classified according to their ante-mortem weight as follows: <10 kg, 10–19 kg, 20–29 kg, and ≥30 kg. Their average age was 8.6 ± 4.5 years. After excision of the heart with its pericardium, the heart was washed and bled for 6 hours in a water source. A surgical silk repair was placed at the most proximal ostium of each coronary artery, and the coronary vasculature was perfused by injection with red mineral dye diluted in semi-synthetic resin (80% Palatal GP40L and 20% styrene). The specimens were preserved in a 10% formaldehyde solution for 96 hours. Subsequently, a 15% KOH solution was used to clear the coronary vasculature of its subepicardial fat and dissected from origin to completion. The caliber of the coronary arteries and their branches was measured 5 mm from their origins using a digital caliper (Mitutoyo®). The trajectories of the coronary vasculature were recorded using the corresponding digital images. The classification of Schlesinger (1940) was used to describe the different types of coronary dominance, and the description of left coronary dominance was enhanced according to the criteria of Didio and Wakefield (1975). The database was recorded in Microsoft Excel 2013, and SPSS 20 software (SPSS, Chicago, IL) was used for statistics. The continuous variables are described with their means and 95% confidence intervals. Using the data normality test for each sample (Kolmogorov–Smirnov), descriptive statistics were estimated for each biometric data. The Student’s t-test was used for quantitative variables in two independent groups. The size and length records are presented as the mean and standard deviation. The value of p < 0.05 was considered the threshold for statistical significance. Ethical approvalThe work was approved by the ethics committee of the Universidad Industrial de Santander (Act 25 - 2024) and complies with the National Law 84 of 1989, corresponding to Chapter VI of the “National Statute for the Protection of Animals,” on the use of animals in experimentation and research. ResultsThirty cardiac specimens with an average weight of 116.35 ± 41.12 g were evaluated, and the average age of all animals was 8.6 +/−4.5 years. Left coronary dominance was observed in all specimens. Subtype II was recorded in 25 (83.3%) specimens, in which the LCA irrigated the LV and the entire interventricular septum, with an SIB emerging from the CXB (Fig. 1). We observed subtype III in 5 (16.7%) hearts, in which we determined that the SIB and right posterior ventricular branches originated from the CXB, supplying the LV, the interventricular septum, and the posterior wall of the RV (Fig. 2). No left subtype I dominance was observed (Table 1). The RCA terminated between the right margin and the crux cordis in 25 (83.3%) hearts and at the acute margin of the heart ending as a right marginal branch in 5 (16.7) cases (Fig. 3). The first segment of this coronary vessel had an average of three branches supplying the anterior wall of the RV, whereas the second segment had two branches supplying the atrial and ventricular rights. The LCA trajectory between the left aortic sinus and its branches’ bifurcation (or trifurcation) was very short (Table 2). In the different groups evaluated, the proximal caliber of the LCA was 2.98 mm, whereas that of the RCA was 1.99 mm (p=0.001; 95% CI: 1.61). The sinoatrial node branch (SANB) arised from the CXB in 4 (13.3%) specimens while in 20 (66.7%) emerged from the RCA and in 6 (20%) specimens we observed a dual origin (LCA and RCA) (Fig. 4 and Table 2). SIB originated from CXB in all cases, ending at the apex in 16 (53.3%) hearts, in the lower third of the subsinusal interventricular sulcus (SIS) in 8 (26.7%) hearts, in the middle third in 5 (16.7%) hearts, and in the upper third in 1 (3.3%) case.

Fig. 1. Diaphragmatic heart surface. Left coronary dominance, subtype II. LV=left ventricle; LA=left atrium; RA=right atrium; RV=right ventricle; CXB=circumflex branch; SIB=subsinusal interventricular branch; LMB=Left marginal branch. Note how the CXB ends as the SIB and its irrigation is terminated in the subsinusal interventricular sulcus.

Fig. 2. Diaphragmatic heart surface. Left coronary dominance, subtype III. LV=left ventricle; LA=left atrium; RA=right atrium; RV=right ventricle; CXB=circumflex branch; SIB=subsinusal interventricular branch; LMB=left marginal branch; CS=coronary sinus; MCV=middle cardiac vein. The CXB ends at the posterior wall of the RV, extending its irrigation area. After its course through the left ventricular atrial groove, the CXB terminated as SIB in 28 (93.3%) cases, whereas it terminated in the posterior aspect of the RV in 6.7%. The length of the CXB was 56.70 mm, which was statistically lower than that of the PIB (p=0.001; CI: 14.38) (Table 2). Table 1. Left coronary dominance subtypes in dogs.

Fig. 3. Anterosuperior view of the heart. RA=right atrium; RV=right ventricle; RCA=right coronary artery. Note the shortness of the RCA, ending at the right edge of the heart.

Fig. 4. Sternocostal surface of the heart. LA=left atrium; LV=left ventricle; RV=right ventricle; PIB=paraconal interventricular branch; CXB=circumflex branch; LMB=left marginal branch. Sinoatrial node branch (arrow) emerging from the CXB. DiscussionWhen describing coronary dominance, the trajectories of the CXB, RCA, and SIB should be evaluated in relation to the myocardial territories they supply on the diaphragmatic surface of the heart. In left-dominant dogs, the LCA and its branches were the primary focus of evaluation. Table 2. Calibers and coronary artery lengths and their main branches in dogs.

In agreement with previous literature, we found left coronary dominance in dogs (Oliveira et al., 2011), similar to that reported in cattle (96.4%) where left coronary dominance was the main finding (Gómez-Torres et al., 2023). On the other hand, humans have mostly right dominance in a range of 55%–84.6%, balanced in 2%–24.5%, and left in 2.4%–8.6% (Didio and Wakefield, 1975; Rojas et al., 1996; Kaletka and Mikusek, 2000; Kaimkhani et al., 2005; Loukas et al., 2006; Ballesteros Acuña et al., 2007), while pigs presented a right coronary dominance pattern reported in 66.5%–100% a balanced dominance pattern of 33.5% (Sahni et al., 2008; Gómez and Ballesteros, 2015). Our study described left coronary dominance according to the DiDio and Wakefield criteria, where in 25 hearts they recorded mostly subtype II dominance (83.3%), which was slightly higher than that reported in cattle (67%) (Gómez-Torres et al., 2023). This subtype was described in 3.3% and 4.8% of previous reports in humans and pigs, respectively (Ballesteros Acuña et al., 2007; Gómez and Ballesteros, 2015). Subtype III was observed in 16.7% of the sample, which was lower than that reported in cattle (33%) (Gómez-Torres et al., 2023), whereas this finding was observed in only 1.9% of the samples from humans and pigs (Ballesteros Acuña et al., 2007; Gómez and Ballesteros, 2015). After the origin of the LCA in the corresponding aortic sinus, a trunk is formed that curves between the left atrium and the pulmonary trunk, to adopt the bifurcated expression, which was higher than described in humans (52%), like pigs (79%) and slightly lower than reported in cattle (87.8%). The trifurcated conformation of the LCA observed in our study was superior to that reported in cattle and pigs, whereas in humans, this feature has been described in 22.1%–42.2% (Ballesteros and Ramirez, 2008; Gómez and Ballesteros, 2014; Gómez-Torres et al., 2023). In most of the hearts evaluated, the CXB terminated in the SIS (93.3%), and this finding is considered a relevant feature of left dominance, contrasting with previous studies in dogs that reported this same end site in 57.7% of cases (Oliveira et al., 2010; Oliveira et al., 2011). Our results agree with those reported in cattle (82.1%) and to a lesser extent with pigs (64% in the posterior aspect of the LV), while in contrast to those described in humans (7%–23%) (10, 22–24) (Didio and Wakefield, 1975; Baptista et al., 1991; Kalpana, 2003). In addition, the PIB was longer than the CXB. Our study observed the SIB emerging from the CXB and terminating mostly in the apex of the heart, whereas Oliveira et al. described it with a shorter course and terminating in the lower third of the SIS (Oliveira et al., 2010; Oliveira et al., 2011). In humans, the posterior interventricular branch terminates between the lower third and the apex in a range of 67.4%–75% (26–28). The termination of this branch in cattle and pigs is consistent with our study (Gómez and Ballesteros, 2013; Gómez-Torres et al., 2023). In this study, SANB originated from the RCA at a frequency comparable to that observed in humans, whereas its origin is exclusively from the RCA in pigs and the LCA in cattle (Olabu et al., 2007; Cademartiri et al., 2008; Ballesteros et al., 2011; Gómez-Torres et al., 2023). A dual origin was observed in 20% of cases, which was higher than the 10% previously reported (Ovcina, 2002). Sinoatrial node irrigation from branches of the RCA and the CXB could explain the resistance to experimentally induced ischemia in dogs in these cases, with this morphological expression acting as a protective factor against arrhythmic and ischemic events (Pina et al., 1975; Okmen and Okmen, 2009; Ballesteros et al., 2011). The strict presentation of left coronary dominance in dogs has been confirmed and is concordant with previous studies (Oliveira et al., 2010; Oliveira et al., 2011). This finding differs from what has been observed in humans and pigs by Gómez-Torres et al. (2023), who present with right dominance with low incidences of left and balanced dominance. This finding in dogs suggests the need for future research into species-specific dominant genetic patterns characteristic of the species that induce this marked phenotype. In an ischemic event involving the dog’s heart, the presence of left dominance implies that LV cardiac failure is accentuated by the impossibility of receiving complementary flow from branches of the RCA (Brookes et al., 1999). However, in clinical cardiology, the capacity of the dog’s cardiac muscle, which sustains compensated cardiac work even with low levels of perfusion and overt hypoxia, can explain the great capacity to maintain ejection rates despite evident hemodynamic compromises (Goto, 2000). ConclusionOur study enhances the concept of left coronary dominance in dogs by classifying it by subtypes, as described in previous studies. Biometric findings improve the information on the anatomy of coronary vessels in dogs and may contribute to the optimization of diagnosis, planning of cardiovascular procedures, and development of personalized clinical interventions in veterinary medicine. AcknowledgmentsSpecial thanks to the veterinary clinics in the city of Bucaramanga, Colombia, for their dedication in providing samples for the development of the study. FundingNone. Authors ContributionThis research was conceptualized by Fabian Gómez-Torres and Luis Ballesteros-Acuña. All authors performed injections of the vascular beds of the hearts and cleaning. Photographs were taken by Iván Andrés Pineda-Betancurt. All authors contributed to the reading, reviewing, revising, and approving of the final version of the manuscript. Conflict of InterestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest. Data AvailabilityAll data supporting this study’s findings are available in the manuscript. ReferencesAuriemma, E., Armienti, F., Morabito, S., Specchi, S., Rondelli, V., Domenech, O., Guglielmini, C., Lacava, G., Zini, E. and Khouri, T. 2018. Electrocardiogram‐gated 16‐multidetector computed tomographic angiography of the coronary arteries in dogs. Vet. Rec. 183(15), 473; doi:10.1136/vr.104711 Ballesteros Acuña, L.E., Corzo Gómez, E.G. and Saldarriaga Tellez, B. 2007. Determinación de la dominancia coronaria en población mestiza colombiana: un estudio anatómico directo. Int. J. Morphol. 25(3), 483–491; doi:10.4067/S0717-95022007000300003 Ballesteros, L.E. and Ramirez, L.M. 2008. Morphological expression of the left coronary artery: a direct anatomical study. Folia Morphol. 67(2), 135–142. Ballesteros, L.E., Ramirez, L.M. and Quintero, I.D. 2011. Right coronary artery anatomy: anatomical and morphometric analysis. Rev. Brasil. Cirurgia Cardiovasc. 26(2), 230–237. Baptista, C.A., Didio, L.J. and Prates, J.C. 1991. Types of division of the left coronary artery and the ramus diagonalis of the human heart. Jpn. Heart J. 32(3), 323–335;veera>10.1536/ihj.32.323 Bertho, E. and Gagnon, G. 1964. A comparative study in three dimension of the blood supply of the normal interventricular septum in human, canine, bovine, porcine, ovine and equine heart. Dis. Chest 46, 251–262; doi:10.1378/chest.46.3.251 Brookes, C., Ravn, H., White, P., Moeldrup, U., Oldershaw, P. and Redington, A. 1999. Acute right ventricular dilatation in response to ischemia significantly impairs left ventricular systolic performance. Circulation 100(7), 761–767. Cademartiri, F., La Grutta, L., Malagò, R., Alberghina, F., Meijboom, W.B., Pugliese, F., Maffei, E., Palumbo, A.A., Aldrovandi, A., Fusaro, M., Brambilla, V., Coruzzi, P., Midiri, M., Mollet, N.R. and Krestin, G.P. 2008. Prevalence of anatomical variants and coronary anomalies in 543 consecutive patients studied with 64-slice CT coronary angiography. Eur. Radiol. 18(4), 781–791;veera>10.1007/s00330-007-0821-9 Cavalcanti, J.S., Oliveira, M.L., Pais e Melo, Jr, A.V., Balaban, G., de Andrade Oliveira, C. L. and de Lucena Oliveira, E. 1995. Anatomic variations of the coronary arteries. Arq. Bras. Cardiol. 65(6), 489–492. Didio, L.J. and Wakefield, T.W. 1975. Coronary arterial predominance or balance on the surface of the human cardiac ventricles. Anat. Anz. 137(1–2), 147–158. Gómez, F.A. and Ballesteros, L.E. 2014. Morphologic expression of the left coronary artery in pigs. An approach in relation to human heart. Rev. Brasil. Cirurgia Cardiovasc. 29(2), 214–220; doi:10.5935/1678-9741.201400270 Gómez, F.A. and Ballesteros, L.E. 2015. Evaluation of coronary dominance in pigs; a comparative study with findings in human hearts. Arq. Brasil. Med. Vet. Zootecnia 67(3), 783–789; doi:10.1590/1678-4162-6637 Gómez, F.A., Ballesteros, L.E. and Cortés, L.E. 2015. Morphological description of great cardiac vein in pigs compared to human hearts. Rev. Bras. Cir. Cardiovasc. 30, 63–69; doi:10.5935/1678-9741.20140101 Gómez-Torres, F.A., Cortés-Machado, L.S. and Ballesteros-Acuña, L.E. 2023. Comparison of coronary arteries morphometry and distribution in bovines with humans and other animal species. Open Vet. J. 13(8), 955–964; doi:10.5455/OVJ.2023.v13.i8.1 Goto, Y. 2000. Left ventricular performance in ischemic right ventricular dysfunction. Circulation 102(15), E107; doi:10.1161/01.cir.102.15.e107 Kaimkhani, Z.A., Ali, M.M. and Faruqi, A.M.A. 2005. Pattern of coronary arterial distribution and its relation to coronary artery diameter. J. Ayub Med. Coll. Abbottabad 17(1), 40–43. Kaletka, Z. and Mikusek, J. 2000. Clinical and morphological studies on varieties of coronary vascularisation of diaphragmatic surface of human heart. Med. Sci. Monit. 6(2), 253–257. Kalpana, R.A. 2003. A study on principal branches of coronary arteries in humans. J. Anat. Soc. India 52(2), 137–140. Loukas, M., Curry, B., Bowers, M., Louis, R.G., Bartczak, A., Kiedrowski, M., Kamionek, M., Fudalej, M. and Wagner, T. 2006. The relationship of myocardial bridges to coronary artery dominance in the adult human heart. J. Anat. 209(1), 43–50;veera>10.1111/j.1469-7580.2006.00590.x Noestelthaller, A., Probst, A. and König, H.E. 2007. Branching patterns of the left main coronary artery in the dog demonstrated by the use of corrosion casting technique. Anat. Histol. Embryol. 36(1), 33–37; doi:10.1111/j.1439-0264.2006.00711.x Okmen, A.S. and Okmen, E. 2009. Sinoatrial node artery arising from posterolateral branch of right coronary artery: definition by screening consecutive 1500 coronary angiographies. Anadolu Kardiyol. Derg. 9(6), 481–485. Olabu, B.O., Saidi, H.S., Hassanali, J. and Ogeng’O, J.A. 2007. Prevalence and distribution of the third coronary artery in Kenyans. Int. J. Morphol. 25(4), 851–854; doi:10.4067/S0717-95022007000400027 Oliveira, C.L., Dornelas, D., De Oliveira Carvalho, M., Wafae, G.C., David, G.S. and Araújo, S. 2010. Anatomical study on coronary arteries in dogs. Eur. J. Anat. 14(1), 1–4. Oliveira, C.L.S.D., David, G.S. and Carvalho, M.D.O. 2011. Anatomical indicators of dominance between the coronary arteries of dogs. Int. J. Morphol. 29(3), 845–849; doi:10.4067/S0717-95022011000300030 Ovcina, F. 2002. Vascularization of the sinoatrial segment in the heart conduction system in bovine and canine hearts. Med. Arh. 56(3), 123–125. Pina, J.A., Pereira, A.T. and Ferreira, A.S. 1975. Arterial vascularization of the sino-auricular node of the heart in dogs. Acta Cardiol. 30(2), 67–77. Rojas, L.R.L., Rojas, L.L., Carpio, J. de L. and Arroyo, A.N.G. 1996. Revisión de 2150 coronariografías. Rev. Cuban. Cardiol. Cir. Cardiovasc. 10, 1. Sahni, D. and Jit, I. 1990. Blood supply of the human interventricular septum in north-west Indians. Indian Heart J. 42(3), 161–169. Sahni, D., Kaur, G.D., Jit, H. and Jit, I. 2008. Anatomy and distribution of coronary arteries in pig in comparison with man. Indian J. Med. Res. 127(6), 564–570. Schlesinger, M.J. 1940. Relation of anatomic pattern to pathologic conditions of the coronary arteries. Arch. Pathol. 30, 403–415. Wagner, R.L., Hood, W.B. and Howland, P.A. 2009. A servo-controlled canine model of stable severe ischemic left ventricular failure. Cardiovasc. Eng. 9(4), 144–152; doi:10.1007/s10558-009-9085-0 World Association of Veterinary Anatomists, International Committee on Veterinary Gross Anatomical Nomenclature. Nomina Anatomica Veterinaria, 16th edition, ICVGAN Editorial Committee, Hanover, 2017. | ||

| How to Cite this Article |

| Pubmed Style Pineda-betancurt IA, Ballesteros-acuña LE, Gómez-torres FA. Coronary dominance assessment in dogs: A comparative study of human and other species. Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(8): 3618-3623. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i8.24 Web Style Pineda-betancurt IA, Ballesteros-acuña LE, Gómez-torres FA. Coronary dominance assessment in dogs: A comparative study of human and other species. https://www.openveterinaryjournal.com/?mno=263338 [Access: January 25, 2026]. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i8.24 AMA (American Medical Association) Style Pineda-betancurt IA, Ballesteros-acuña LE, Gómez-torres FA. Coronary dominance assessment in dogs: A comparative study of human and other species. Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(8): 3618-3623. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i8.24 Vancouver/ICMJE Style Pineda-betancurt IA, Ballesteros-acuña LE, Gómez-torres FA. Coronary dominance assessment in dogs: A comparative study of human and other species. Open Vet. J.. (2025), [cited January 25, 2026]; 15(8): 3618-3623. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i8.24 Harvard Style Pineda-betancurt, I. A., Ballesteros-acuña, . L. E. & Gómez-torres, . F. A. (2025) Coronary dominance assessment in dogs: A comparative study of human and other species. Open Vet. J., 15 (8), 3618-3623. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i8.24 Turabian Style Pineda-betancurt, Iván Andrés, Luis Ernesto Ballesteros-acuña, and Fabián Alejandro Gómez-torres. 2025. Coronary dominance assessment in dogs: A comparative study of human and other species. Open Veterinary Journal, 15 (8), 3618-3623. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i8.24 Chicago Style Pineda-betancurt, Iván Andrés, Luis Ernesto Ballesteros-acuña, and Fabián Alejandro Gómez-torres. "Coronary dominance assessment in dogs: A comparative study of human and other species." Open Veterinary Journal 15 (2025), 3618-3623. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i8.24 MLA (The Modern Language Association) Style Pineda-betancurt, Iván Andrés, Luis Ernesto Ballesteros-acuña, and Fabián Alejandro Gómez-torres. "Coronary dominance assessment in dogs: A comparative study of human and other species." Open Veterinary Journal 15.8 (2025), 3618-3623. Print. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i8.24 APA (American Psychological Association) Style Pineda-betancurt, I. A., Ballesteros-acuña, . L. E. & Gómez-torres, . F. A. (2025) Coronary dominance assessment in dogs: A comparative study of human and other species. Open Veterinary Journal, 15 (8), 3618-3623. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i8.24 |