| Research Article | ||

Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(9): 4082-4089 Open Veterinary Journal, (2025), Vol. 15(9): 4082-4089 Research Article Prevalence and molecular identification of Giardia intestinalis in water buffalo in IraqHaider H. Alseady1*, Sahad M. K. Al-Dabbagh2 and and Saif A. J. Al-Shalah11Department of Medical Laboratory Techniques, Technical Institute of Babylon, Al-Furat Al-Awsat Technical University (ATU), Babylon, Iraq 2Department of Medical Laboratory Techniques, Institute of Medical Technology Al-Mansour, Middle Technical University (MTU), Baghdad, Iraq *Corresponding Author: Haider H. Alseady. Department of Medical Laboratory Techniques, Technical Institute of Babylon, Al-Furat Al-Awsat Technical University (ATU), Babylon, Iraq. Email: haider.alseady.dw [at] atu.edu.iq Submitted: 16/05/2025 Revised: 07/08/2025 Accepted: 18/08/2025 Published: 30/09/2025 © 2025 Open Veterinary Journal

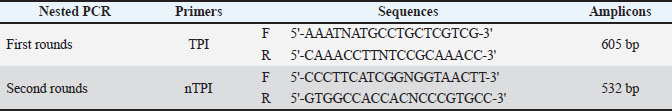

ABSTRACTBackground: Giardia is the most prevalent flagellated protozoan in humans and other mammals. It causes significant economic losses in livestock, including water buffaloes. Aim: This study aimed to determine the prevalence rate of Giardia intestinalis in water buffaloes (Bubalus bubalis) using microscopic and molecular techniques and to detect the genotypes of Giardia isolates from water buffaloes in Iraq. Methods: A total of 180 fecal samples (82 males, 98 females) were collected from water buffaloes in the Babylon province. The microscopic method was used to determine the infection rate of G. intestinalis in water buffalo in the Babylon province. DNA was extracted using the fecal lysis procedure and proteinase K, nested-polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was used to identify the prevalence of Giardia assemblages in water buffalo, targeting the triose phosphate isomerase (TPI) gene. Ten PCR-positive samples were sent for sequence analysis. Results: The infection rate of G. intestinalis was 13.88% using the conventional microscopic method and 30.55% using nested PCR in water buffalo. There was no significant difference in the prevalence of Giardia between males (29.26%) and females (31.63%). The largest infection rate was observed in buffaloes aged 1 year (34.24%), while the lowest was observed in those aged 3 years (26.66%). Phylogenetic analysis identified two genotypes of G. intestinalis, assemblages A and B, in Iraqi water buffaloes. Conclusion: The identification of G. intestinalis assemblages A and B in buffalo indicated that buffalo acts as a reservoir host and may be a source of zoonotic transmission. Keywords: Assemblages, Giardia intestinalis, Prevalence, TPI gene, Water buffalo. IntroductionGiardia intestinalis, duodenalis,and lamblia are common gastrointestinal parasitesin humans and animals worldwide (Feng and Xio, 2011). It has socioeconomic and public health impacts. Giardia is characterized by mild to moderate diarrhea with no symptoms in water buffalo. However, infected buffaloes manifest weight loss, lethargy, and lower productivity. In severe cases, soft stools, a rough coat, intestinal gas, and weight loss may be present (Helmy et al., 2014; Koehler et al., 2014). In humans, most people experience a mild form of giardiasis with no symptoms; nevertheless, persistent diarrhea (steatorrhea), epigastric tenderness, abdominal cramps, flatulence, malabsorption, dehydration, and weight loss may occur in severe cases (Halliez and Buret, 2013). Giardia is spread by the direct oral fecal route, contact with infected mammal feces, and tainted food, water, or drink. The infectious stage of Giardia, the cyst, has been identified in a variety of foods (vegetables, fruit, and meat) and contributes to the spread of illness. It can live in water and soil for several months (Cacciò et al., 2018; Dixon, 2021). Calves are a major source of human infections, and significantly contribute to environmental contamination by releasing large amounts of cysts into the environment and contaminating drinking water sources (Toledo et al., 2017; Alhayali et al., 2020). Different animal species are infected by eight assemblages of G. intestinalis (A–H). Dogs, cats, livestock, and wild animals are the sources of Giardia assemblages A and B that infect humans. Ruminants are believed to be the primary source of giardiasis outbreaks due to their massive fecal production (Wang et al., 2014; Efstratiou et al., 2017; Jian et al., 2018; Bartley et al., 2019; Capewell et al., 2021). Buffaloes are an endangered and significant ruminant species. Similar to other ruminants, G. intestinalis assemblages A, B, and E have been identified as reservoir hosts for giardiasis (Soysal, 2013; Abeywardena et al., 2014; Helmy et al., 2014; Kılınç et al., 2023). Water buffaloes are common in the Southeast Asian region because they are raised for agricultural practices and as meat products with integrated crop-livestock farming systems. They graze in nearby public areas might pollute the environment, resulting in an impact on human or animal health (Perera, 2011). In Iraq, water buffaloes play an important role as a source of milk, meat, manure, and drought power (Obayes et al., 2016; Tokseiit et al., 2023). Few studies have been conducted on the incidence of Giardia in buffaloes and how they may spread zoonotic Giardia species. This study aimed to determine the prevalence of G. intestinalis in water buffaloes (Bubalus bubalis) using both traditional microscopic and molecular techniques. In addition, we sought to identify the genotypes of Giardia isolates through phylogenetic analysis to assess the risk factors for zoonotic transmission in other hosts in the Babylon province, Iraq. Materials and MethodsSample collectionA total of 180 fecal samples (82 males and 98 females) were randomly collected from domestic water buffalo of different ages in Babylon province from March to September 2024. The sampling was carried out using the following protective measures. The fecal samples were stored in a sterile container, sealed tightly, and sequentially numbered along with the sample date, age, and sex. The samples were taken to the parasitology laboratory at the Technical Institute of Babylon of Al-Furat Al-Awsat Technical University, where they were separated into two sections for microscopic analysis and DNA extraction. Microscopic examinationThe microscopic (floatation) method was used to detect the prevalence of G. intestinalis in water buffalo (Uchôaet al., 2018). Molecular techniqueDNA was extracted using the fecal lysis procedure and Proteinase K protocol for the DNA extraction kit for stools according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Bioneer). Subsequently, the extracted gDNA was evaluated using a nano-drop spectrophotometer and stored in a refrigerator at −20C, until it was used for polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification. A nested PCR pathway was used for the detection of G. intestinalis assemblages based on the triose phosphate isomerase (TPI) specific gene from the fecal samples of water buffalo. Primers that were donated by (The Bioneer Company) and specifically designed for genotyping G. intestinalis were used in accordance with the method reported by (Cacciò et al., 2008), as shown in Table 1. Table 1. Primers targeting triose phosphate isomerase-specific gene for Giardia detection.

PCR reagents were combined as per the PCR premix kit instructions, using Tris-HCl (pH 9.0), dNTPs 250 mM, Taq DNA polymerase 1U, and the freeze-dried pellet premix from the PCR premix container (10 mM, containing 1.5 mM MgCl2, 30 mM KCl, stabilizer, and tracking dye). According to the kit’s instructions, a total volume of pure genomic DNA 20, 1.5 µl of 10 pmole from forward primer, and 1.5 µl of 10 pmole from reverse primer were added to create the master mix of the PCR. Deionized PCR water was then added to the 20 µl PCR premix tube, and an Exispin vortex was used for centrifugation of the mixture. There were 35 cycles: initial denaturation at 95°C for 1 minutes, annealing at 55°C for 1 minute, extension at 72°C for 1 minute, and final extension at 72°C for 5 minutes. PCR products were viewed using agarose gel electrophoresis with 1.5% ethidium bromide staining and transilluminator visualization (UV) to examine the PCR data. Ten PCR-positive samples were sent for sequence analysis. Sequence analysisMolecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 11.0 (MEGA 11) was used to conduct DNA sequence analysis. The phylogenetic tree Maximum Likelihood method was used to calculate the development distances, and ClustalW alignment was used to determine the multiple sequence alignment of the TPI gene (Tamura et al., 2021). Statistical analysisStatistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 23.0, and the chi-square test was used to estimate the variables and examine how different numbers were statistically significant. Variation was considered significant at p < 0.05 (Daniel and Cross, 2018). Ethical approvalAll procedures in this study were approved by the Animals and Ethics Committee of Middle Technical University in Iraq (No: 92, AD. 2/5/2025)in compliance with the ethical principles of animal welfare. ResultsMicroscopic examinationThe cysts examination of G. intestinalis in water buffalo fecal samples appeared oval with a thick wall, longitudinal fibrils consisting of axostyle, and four nuclei at 40× examined by the floatation method. Measurement of the cysts with an average length of (13–15 μm) and a width of (8–10 μm) (Fig. 1).

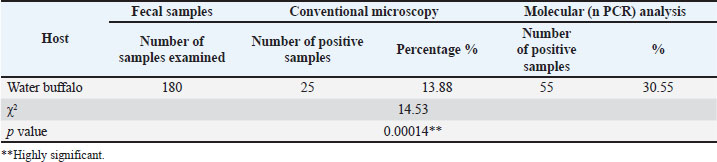

Fig. 1. Concentration method for Giardia intestinalis cyst in fecal samples of water buffalo, oval in shape with four nuclei (100×). Total infection rate of G. intestinalis in water buffaloThe prevalence of G. intestinalis in water buffalo showed a significant (p < 0.05) difference between the microscopic (13.88%) and molecular (30.55%) nPCR techniques (Table 2). Table 2. Total infection rate of Giardia intestinalis in water buffalo by microscopic and molecular (PCR).

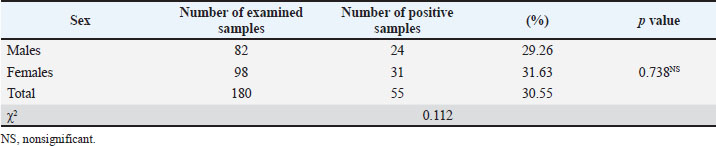

Infection rate of G. intestinalis according to sexNo significant (p > 0.05) difference in G. intestinalis was observed between males (29.26%) and females (31.63%) (Table 3). Table 3. Infection rate of G. intestinalis in water buffalo according to sex.

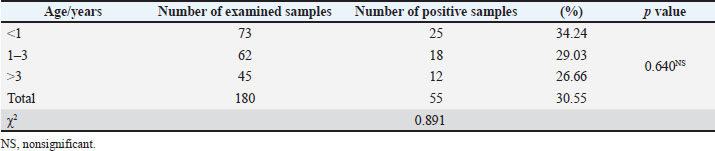

Infection rate of G. intestinalis according to ageA higher infection rate (34.24%) of G. intestinalis was observed in water buffalo less than 1 year old, followed by those between 1–3 years (29.03%), and the lowest infection rate was observed at age >3 years (26.66%), with no significant differences (p > 0.05) (Table 4). Table 4. Infection rate of G. intestinalis in water buffalo according to age.

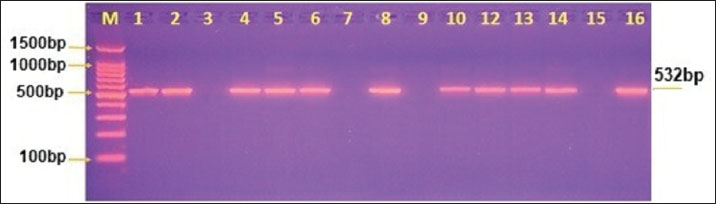

Molecular distribution of G. intestinalis assemblages in water buffaloGenomic DNA obtained from water buffalo fecal samples was used for molecular analysis by nested PCR using TPI gene-specific primers to identify G. intestinalis genotypes. The presence of G. intestinalis was confirmed in all samples by nested PCR, which showed a clear band of 532 bp on an agarose gel electrophoresis (Fig. 2).

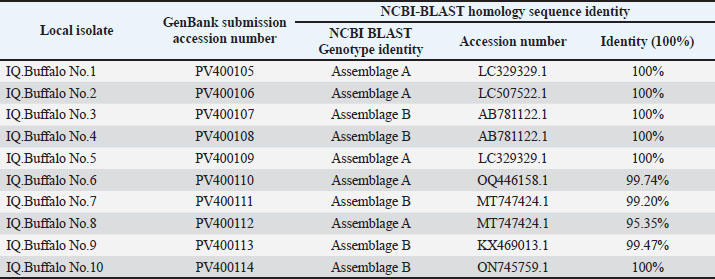

Fig. 2. Image from an agarose gel electrophoresis showing the analysis of theTPI gene by nPCR in fecal samples from G. intestinalis. (M) Marker rung (1,500–100 bp). Lane (1–16) 532-bp nPCR product for G. intestinalis. Two assemblages (genotypes) of G. intestinalis were detected in water buffalo by sequence analysis of 10 positive samples: G. intestinalis assemblage A (5/10) and G. intestinalis assemblage B (5/10) (Figs. 3 and 4) (Table 5). Table 5. NCBI-BLAST homology sequence identity between local G. intestinalis assemblage’s buffalo isolates with G. intestinalis assemblages-related genotypes isolates.

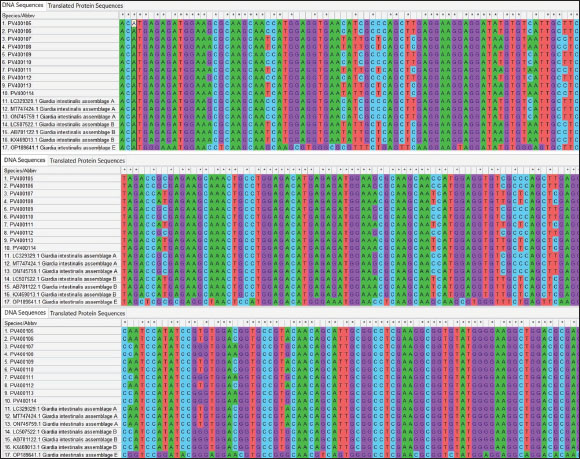

Fig. 3. CLUSTALW was used to compare the partial sequence of the TPI gene in local G. intestinalis Buffalo isolates with NCBIBLAST isolates of G. intestinalis-related genotypes. The TPI gene nucleotide sequences of the buffalo isolates were subjected to multiple alignment analysis, which revealed genetic variation (substitution mutation) and similarity (*).

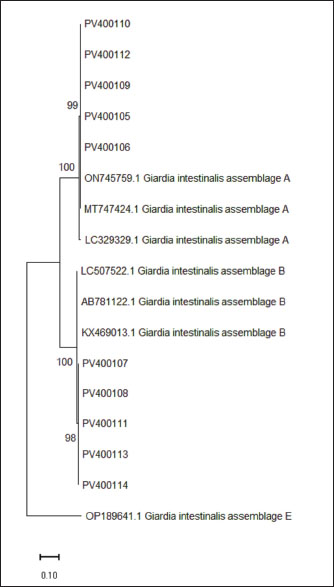

Fig. 4. Phylogenetic tree analysis based on the partial sequencing of the (TPI) gene in local isolates of G. intestinalis IQ Buffalo was used to analyze genetic relationships. The phylogenetic tree was created using the maximum likelihood method in MEGA 11.0. The local isolates of G. intestinalis (PV400105, PV400106, PV400109, PV400110, and PV400112) were found to be closely related to NCBIBLAST G. intestinalis isolate A (assemblage A: LC329329.1, OQ446158.1, MT747424.1, and ON745759.1), whereas the local isolates of G. intestinalis (PV400107, PV400108, PV400111, PV400113, and PV400114) were closely related to NCBI-BLAST G. intestinalis isolate B (assemblage B: LC507522.1, AB781122.1, and KX469013.1) at total genetic changes (0.00%–0.10%). Estimation of the genetic diversity of G. intestinalis assemblages in water buffaloThe number of base substitutions per site is displayed based on the assessment of the net average between sequence groups. Variations in composition bias between sequences were considered in evolutionary comparisons. Thirteen sequences were analyzed. Missing data, unclear bases, and alignment gaps with 0% were permitted at any place (partial deletion option), whereas all positions with 100% site coverage were removed. The final dataset contained 311 locations in total. Evolution analysis was done in (MEGA 11). DiscussionThe morphological characteristics and measurements of G. intestinalis cysts were in accordance with those of AI-Fetly et al. (2010) in Iraq, who found that the size of cysts was (14.32 ± 0.244 × 9.43 ± 0.261 μm) also Al-Saad and Al-Emarah (2014) also recognized cysts of (9–14 × 6–11 μm) in humans and (8–14 – 6–10 μm) in cow. The prevalence of G. intestinalis was 13.88% by the microscopic method and 30.55% by nPCR in water buffaloes in the province of Babylon, Iraq. These results could be explained by the fact that larger amounts of genetic material in the aliquot utilized for DNA extraction would arise from a fecal sample’s diverse distribution of cysts, indicating that the nPCR technique was more accurate, specific, and sensitive than the microscopic method (Feng and Xio, 2011; Abdullah et al., 2017). Microscopic detection of G. intestinalis was 13.88%. This result was higher than that recorded by 10.9% of Egyptian buffaloes (Helmy et al., 2014), 12.5% of water buffaloes in Babylon province, Iraq (Obayes et al., 2016), and 8% of Turkish water buffalo (Kılınç et al., 2023), but lower than that recorded in India (24.16%) using Lugol’s iodine stain (Negi et al., 2022). The molecular detection rate of G. intestinalis was 30.55%. This result was higher than that recorded 2.6% in Romanian buffaloes (Barburaș et al., 2021), 11% in Turkey (Kılınç et al., 2023), and in Iraq, 25% (Tokseiit et al., 2023). The risk of infection will be significantly influenced by several factors, including the number of samples collected, management, water sources, and the general hygiene conditions of the farms. In relation to sex, no significant difference was found between sex and the prevalence of G. intestinalis in water buffalo. These results were in agreement with those of Negi et al. (2022), who showed that female buffalo had a higher prevalence (31.32%) than male buffalo (21.62%) in India, and Iraq (Tokseiit et al., 2023), who showed that there were 7 males (41.6%) and 9 females (58.33%), respectively, but disagreed with those of Obayes et al. (2016), who showed that males (11.6%) had a slightly higher than females (8.8%) in Babylon province. The infection rate in females was numerically higher prevalence than that in the males, but no statistically significant differences was existed, this could be a clear result from this study and other prevalence studies when the mixed rearing (males and females) shown no variation in the prevalence rate with this parasite, but it is clear that the females showed a higher prevalence rate of infection compared with males as a result of stress factors faced by the females, particularly pregnancy and lactation. The findings revealed a significant difference in water buffalo prevalence rates across various age groups. The age groups 1 and >3 years had the highest and lowest infection rates, respectively. The high infection rate among young buffaloes is due to the presence of animal carriers, mixed rearing, and an incomplete immune system in these young animals, demonstrating an adverse correlation between the host’s age and the prevalence rate. These findings were consistent with those of earlier research, which demonstrated that the prevalence of infection initially emerged between the ages of 6 months and 2 years, after which the infection declined (Obayes et al., 2016; De Aquino et al., 2020; Negi et al., 2022; Tokseiit et al., 2023). The phylogenetic tree including sequences from the neighboring country of Iraq shows a matching percentage of accession numbers from the current study (PV400105, PV400106, PV400109, PV400110, and PV400112)were 100% of G. intestinalis assemblage A with accession number (LC329329.1), isolatedfrom municipal waste collection workers in Iran and 99.74% with accession number (OQ446158.1), isolated from humans in the east of Iran. G. intestinalis assemblage B recorded that accession no. from the current study (PV400108, PV400108, PV400111, PV400113, and PV400114) were 100% of G. intestinalis assemblage B with accession number (AB781122.1), isolated from human and dairy cattle in Egypt, and 99.47% with accession number (KX469013.1), isolated from humans in Spain. Water buffalo may be a major reservoir of Giardia infection, significantly contributing to environmental contamination by releasing large amounts of cysts into the environment and contaminating animal and drinking water. This study strongly indicates that water buffalo in Iraq could play an important role in the spread of Giardia zoonotic assemblages. Few studies have examined the frequency and genotypes of giardiasis in water buffaloes, an important ruminant species. Giardia assemblages A and B were found in studies on buffaloes from other countries (Utaaker et al., 2018; De Aquino et al., 2020; Kılınç et al., 2023), similar to those assemblages found in Iraqi water buffaloes. These are also the provinces where human cases of G. intestinalis assemblage B have been documented (Ertug et al., 2016). Giardia intestinalis ensemble B is primarily found in humans and is thought to be the cause of chronic illnesses in people. Its isolation from domestic animals further determines that it is an anthropozoonotic assemblage (Mohammed Mahdy et al., 2009; Heyworth, 2016). This study represents the first report of assemblages A and B in buffaloes. Climate, immune status, managerial circumstances, and methodology are some of the factors that contribute to the variations between the studies. ConclusionThe detection of G. intestinalis assemblages A and B in water buffalo indicated that buffaloes play an important role as reservoir hosts and can pose a risk to other animals by close contact or contamination of water and soil. The results show that G. intestinalis is common in pre-weaned calves and may contribute to the spread of zoonotic assemblages A and B infecting humans. AcknowledgmentsThe authors would like to thank all animal owners for cooperating with them in collecting fecal samples from different areas in Babylon province. Conflict of interestThere was no conflicting interest. FundingNone. Authors’ contributionH.H., S.M., and S.A.: Conceptualization and date duration. H.H.: Formal analyses. Writing an original draft. S.A.: Writing-reviewing and editing. H.H. and S.M.: Methodology. All authors: manuscript revision and approval of the submitted version. Data availabilityAll data were provided in the manuscript. ReferencesAbdullah, D., Jesse, F.F., Lim, Y.A.L. and Sharma, R.S.K. 2017. Molecular epidemiology, risk factors of zoonotic enteric protozoa and genetic diversity of Blastocystis infecting cattle in Peninsular Malaysia. Pathogens, 1–73; doi:10.3390/pathogens12111359 Abeywardena, H., Jex, A.R., Koehler, A.V., Rajapakse, R.J., Udayawarna, K., Haydon, S.R. and Gasser, R.B. 2014. First molecular characterization of Cryptosporidium and Giardia from bovines (Bos taurus and Bubalus bubalis) in Sri Lanka: unexpected absence of C. parvum from pre-weaned calves. Paras. Vectors 7, 1. AI-Fetly, D.R., Airodhan, M.A. and Abid, T.A. 2010. Epidemiological and therapeutical study of Giardiasis in sheep in AL-Diwaniya province. Kufa J. For Vet. Med. Sci. 1(1), 28–40; doi:10.36326/kjvs/2010/v1i14224 Al-Saad, R. and Al-Emarah, G. 2014. Morphological descriptive study of Giardia lamblia in man and cow at basrah. Int. J. Biol. Res. 2(2), 125–128. Barburaș, D.A., Cozma, V., Ionica, A.M., Abbas, I., Bărburaș, R., Mircean, V. and Gyorke, A. 2021. Intestinal parasites of buffalo calves from romania: molecular characterization of Cryptoporidium spp. and Giardia duodenalis, and the first report of Eimeria bareillyi. Res. Sq. 4(International License), 1–14; doi: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-151344/v1 Bartley, P.M., Roehe, B.K., Thomson, S., Shaw, H.J., Peto, F., Innes, E.A. and Katzer, F. 2019. Detection of potentially human infectious assemblages of Giardia duodenalis in fecal samples from beef and dairy cattle in Scotland. Parasitology 146(9), 1123–1130; doi:10.1017/S0031182018001117 Cacciò, S.M., Beck, R., Lalle, M., Marinculic, A. and Pozio, E. 2008. Multilocus genotyping of Giardia duodenalis reveals striking differences between assemblages A and B. Int. J. for Parasitology 38(13), 1523–1531; doi:10.1016/j.ijpara.2008.04.008 Cacciò, S.M., Lalle, M. and Svärd, S.G. 2018. Host specificity in the Giardia duodenalis species complex. Infect. Genet. Evol. 66, 335–345; doi:10.1016/j.meegid.2017.12.001 Capewell, P., Krumrie, S., Katzer, F., Alexander, C.L. and Weir, W. 2021. Molecular epidemiology of Giardia infections in the genomic era. Trends Parasitol. 37(2), 142–153. Daniel, W.W. and Cross, C.L. 2018. Biostatistics: a foundation for analysis in the health sciences, 9th ed. Las Vegas, NV: John Wiley and Sons, Inc. De Aquino, M.C.C., Inácio, S.V., Rodrigues, F.D.S., De Barros, L.D., Garcia, J.L., Headley, S.A., Gomes, J.F. and Bresciani, K.D.S. 2020. Cryptosporidiosis and Giardiasis in Buffaloes (Bubalus bubalis). Front. Vet. Sci. 7, 7; doi:10.3389/fvets.2020.557967 Dixon, B.R. 2021. Giardia duodenalis in humans and animals - transmission and disease. Res. Vet. Sci. 135, 283–289; doi:10.1016/j.rvsc.2020.09.034 Efstratiou, A., Ongerth, J. and Karanis, P. 2017. Evolution of monitoring for Giardia and Cryptosporidium in water. Water Res. 123, 96–112; doi:10.1016/j.watres.2017.06.042 Ertuğ, S., Ertabaklar, H., Özlem Çalişkan, S., Malatyali, E. and Bozdoğan, B. 2016. Genotyping of Giardia intestinalis strains isolated from humans in Aydin, Turkey. Mikrobiyoloji. Bulteni. 50(1), 152–158; doi:10.5578/mb.10387 Feng, Y. and Xiao, L. 2011. Zoonotic potential and molecular epidemiology of Giardia species and giardiasis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 24(1), 110–140; doi:10.1128/CMR.00033-10 Halliez, M.C. and Buret, A.G. 2013. Extra-intestinal and long term consequences of Giardia duodenalis infections. World J. Gastroenterol. 19(47), 8974–8985; doi:10.3748/wjg.v19.i47.8974 Helmy, Y.A., Klotz, C., Wilking, H., Krücken, J., Nockler, K., Von Samson-himmelstjerna, G. and Aebischer, T. 2014. Epidemiology of Giardia duodenalis infection in ruminant livestock and children in the Ismailia province of Egypt: insights by genetic characterization. Parasites vectors 7, 1–11; doi:10.1186/1756-3305-7-321 Heyworth, M.F. 2016. Giardia duodenalisgenetic assemblages and hosts. Parasite 23, 13; doi:10.1051/parasite/2016013 Jian, Y., Zhang, X., Li, X., Karanis, G., Ma, L. and Karanis, P. 2018. Prevalence and molecular characterization of Giardia duodenalis in cattle and sheep from the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau Area (QTPA), northwestern China. Vet. Parasitology 250, 40–44; doi:10.1016/j.vetpar.2017.12.001 Kılınç, O.O., Ayan, A., Çelik, B.A., Çelik, O.Y., Yüksek, N., Akyıldız, G. and Oğuz, F.E. 2023. The investigation of Giardiasis (foodborne and waterborne diseases) in buffaloes in Van Region, Türkiye: first molecular report of Giardia duodenalis Assemblage B from Buffaloes. Pathogens 12(1), 106; doi:10.3390/pathogens12010106 Koehler, A.V., Jex, A.R., Haydon, S.R., Stevens, M.A. and Gasser, R.B. 2014. Giardia/giardiasis — A perspective on diagnostic and analytical tools. Biotechnol. Adv. 32(2), 280–289; doi:10.1016/j.biotechadv.2013.10.009 Mohammed Mahdy, A.K., Surin, J., Wan, K.L., Mohd-Adnan, A., Al-Mekhlafi, M.S.H. and Lim, Y.A.L. 2009. Giardia intestinalis genotypes: risk factors and correlation with clinical symptoms. Acta Trop. 112(1), 67–70; doi:10.1016/j.actatropica.2009.06.012 Negi, D., Rashid, M., Singh, M., Malik, M.A. and Sharma, H.K. 2022. Prevalence and associated risk factors of giardiasis in buffalo calves of nomadic communities, Jammu and Kashmir, India. Buffalo Bull. 41(3), 423–430; doi:10.56825/bufbu.2022.4133223 Obayes, H.H., Al-Rubaie, H.M., Zayer, A.A.J. and Radhy, A.M. 2016. Detection of the prevalence of some gastrointestinal protozoa in buffaloes of Babylon Governorate. Basrah J. Vet. Res. 15(2), 294–303. Perera, B.M. 2011. Reproductive cycles of buffalo. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 124(3-4), 194–199; doi:10.1016/j.anireprosci.2010.08.022 Soysal, M. 2013. Anatolian water buffaloes husbandry in Turkey. Buffalo Bull 32, 293–309. Tamura, K., Stecher, G. and Kumar, S. 2021. MEGA11: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol. 38(7), 3022–3027; doi:10.1093/molbev/msab120 Tokseiit, Y., Albahadly, W.K.Y., Radhi, H., Abduljabbar, M.H., Ahmed, M., Alwash, S.W. and Saule, J. 2023. Determination of Giardia duodenalis (Metamonada: hexamitidae) genotypes in water buffalo. Caspian J. Environ. Sci. 21(2), 389–393; doi:10.22124/CJES.2023.6531 Toledo, R.D.S., Martins, F.D.C., Ferreira, F.P., de Almeida, J.C., Ogawa, L., dos Santos, H.L.E.P.L., Dos Santos, M.M., Pinheiro, F.A., Navarro, I.T., Garcia, J.L. and Freire, R.L. (2017) Cryptosporidium spp. and Giardia spp. in feces and water and the associated exposure factors on dairy farms. PLoS One 12(4), e0175311; doi:10.1371/journal. pone.0175311 Uchôa, F.F.M., Sudré, A.P., Campos, S.D.E. and Almosny, N.R.P. 2018. Assessment of the diagnostic performance of four methods for the detection of Giardia duodenalis in fecal samples from human, canine and feline carriers. J. Microbiol. Methods 145, 73–78; doi:10.1016/j.mimet.2018.01.001 Utaaker, K.S., Chaudhary, S., Bajwa, R.S. and Robertson, L.J. 2018. Prevalence and zoonotic potential of intestinal protozoans in bovines in Northern India. Vet. Parasitol. Reg. Stud. Reports 13, 92–97; doi:10.1016/j.vprsr.2018.03.008 Wang, H., Zhao, G., Chen, G., Jian, F., Zhang, S., Feng, C., Wang, R., Zhu, J., Dong, H., Hua, J., Wang, M. and Zhang, L. 2014. Multilocus genotyping of Giardia duodenalis in dairy cattle in Henan, China. PLoS One 9(6), e100453; doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0100453 | ||

| How to Cite this Article |

| Pubmed Style Alseady HH, Al-dabbagh SMK, Al-shalah SAJ. Prevalence and molecular identification of Giardia intestinalis in water buffalo in Iraq. Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(9): 4082-4089. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i9.12 Web Style Alseady HH, Al-dabbagh SMK, Al-shalah SAJ. Prevalence and molecular identification of Giardia intestinalis in water buffalo in Iraq. https://www.openveterinaryjournal.com/?mno=258715 [Access: January 25, 2026]. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i9.12 AMA (American Medical Association) Style Alseady HH, Al-dabbagh SMK, Al-shalah SAJ. Prevalence and molecular identification of Giardia intestinalis in water buffalo in Iraq. Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(9): 4082-4089. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i9.12 Vancouver/ICMJE Style Alseady HH, Al-dabbagh SMK, Al-shalah SAJ. Prevalence and molecular identification of Giardia intestinalis in water buffalo in Iraq. Open Vet. J.. (2025), [cited January 25, 2026]; 15(9): 4082-4089. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i9.12 Harvard Style Alseady, H. H., Al-dabbagh, . S. M. K. & Al-shalah, . S. A. J. (2025) Prevalence and molecular identification of Giardia intestinalis in water buffalo in Iraq. Open Vet. J., 15 (9), 4082-4089. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i9.12 Turabian Style Alseady, Haider H., Sahad M. K. Al-dabbagh, and Saif A. J. Al-shalah. 2025. Prevalence and molecular identification of Giardia intestinalis in water buffalo in Iraq. Open Veterinary Journal, 15 (9), 4082-4089. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i9.12 Chicago Style Alseady, Haider H., Sahad M. K. Al-dabbagh, and Saif A. J. Al-shalah. "Prevalence and molecular identification of Giardia intestinalis in water buffalo in Iraq." Open Veterinary Journal 15 (2025), 4082-4089. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i9.12 MLA (The Modern Language Association) Style Alseady, Haider H., Sahad M. K. Al-dabbagh, and Saif A. J. Al-shalah. "Prevalence and molecular identification of Giardia intestinalis in water buffalo in Iraq." Open Veterinary Journal 15.9 (2025), 4082-4089. Print. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i9.12 APA (American Psychological Association) Style Alseady, H. H., Al-dabbagh, . S. M. K. & Al-shalah, . S. A. J. (2025) Prevalence and molecular identification of Giardia intestinalis in water buffalo in Iraq. Open Veterinary Journal, 15 (9), 4082-4089. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i9.12 |