| Research Article | ||

Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(6): 2849-2860 Open Veterinary Journal, (2025), Vol. 15(6): 2849-2860 Research Article Effect of heat treatment of canola seed and its meal on nutrients degradability, ruminal fermentation, and ruminal biohydrogenation of unsaturated fatty acids using rumen simulation technique (Rusitec)Mohammed Sami Aleid1, Sherief M. Abdel-Raheem1*, Mohsen M. Farghaly2, Ibrahim M. I. Youssef3, Hayam M. A. Monzaly4, Alhosein Hamada5, Saad Shousha6 and Waleed K. Abouamra71Department of Public Health, College of Veterinary Medicine, King Faisal University, Hofuf, Saudi Arabia 2Department of Animal Production, Faculty of Agriculture, Assiut University, Assiut, Egypt 3Department of Nutrition and Clinical Nutrition, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Beni-Suef University, Beni-Suef, Egypt 4Sheep and Goat Research Department, Animal Production Research Institute, Agriculture Research Center, Giza, Egypt 5College of Agricultural and Food Sciences, King Faisal University, Hofuf, Saudi Arabia 6Department of Biomedical Sciences, College of Veterinary Medicine, King Faisal University, Hofuf, Saudi Arabia 7Department of Animal Production, Faculty of Agriculture, Al-Azhar University, Assiut, Egypt *Correspondence to: Sherief M. Abdel-Raheem. Department of Public Health, College of Veterinary Medicine, King Faisal University, Hofuf, Saudi Arabia. Email: sdiab [at] kfu.edu.sa Submitted: 25/04/2025 Revised: 07/05/2025 Accepted: 08/05/2025 Published: 30/06/2025 © 2025 Open Veterinary Journal

AbstractBackground: One possible method to improve ruminant nutrient utilization is heat treatment of feed ingredients, such as canola seed and its meal, to reduce ruminal degradation of proteins and unsaturated fatty acids (FA). Objective: The study evaluates the impact of heat treatment of canola seed and its meal on nutrient degradation, ruminal biohydrogenation of unsaturated FA, and rumen liquor parameters. Methods: Four degradability trials were conducted using the rumen simulation technique (Rusitec) with four vessels. Untreated whole canola seeds, heated whole canola seeds, untreated canola meal, and heated canola meal at 127°C for 15 minutes were used as four treatments in four separate trials. Results: Heat treatment of whole canola seed and its meal decreased the rumen degradability of most nutrients, especially crude protein and crude fat, and reduced the rumen ammonia concentration. Moreover, the heat treatment of whole canola seed decreased the rumen biohydrogenation of mono unsaturated FA, polyunsaturated FA, and total long-chain FA contents. Heat-treated canola seed and meal had an increase in the total volatile FA content (especially acetate, propionate, and iso-valerate) of the rumen fluid when compared to the untreated groups. Conclusion: From the obtained results, it could be concluded that the heat treatment of whole canola seed and its meal was effective in protecting the dietary crude protein from rumen degradation, and also the unsaturated FA from ruminal biohydrogenation. Heat treatment increases the rumen bypass of both amino acids and unsaturated FA from canola seeds and meals, which are essential in improving the productive performance of ruminants. Keywords: Heat treatment, Canola seed, Fatty acids, Biohydrogenation, Rumen bypass protein, Rumen, Rusitec. IntroductionTraditional sources of protein like cottonseed cake and soybean meal serve as the main protein sources for ruminants worldwide. Recently, there is a shortage in these sources, which has also more expensive. Therefore, it is necessary to look for alternative oil seed crops that can provide a high-quality by-product to replace soybean meal and cottonseed cake. Canola is an oil-seed plant derived from rapeseed (Brassica napus and Brassica campestris/rapa). Canola has less quantities of “erucic acid” than conventional rape seed (Bell, 1993). Canola seed can be added to ruminant rations as a protein and/or lipid source, as it contains 42%–43% ether extract (EE), principally triglycerides, and about 20% crude protein (CP) (Leupp et al., 2006). Moreover, canola oil is rich in unsaturated fatty acids (FA), which helps shift the fatty acid profile of ruminant products toward a higher proportion of unsaturated C18 FA—making up over 60% of total FA an advantage for health-conscious consumers (Delbecchi et al., 2001). In contrast, canola meal, which remains after the oil is extracted from the seeds, is an excellent protein source with at least 34% protein (COPA, 1998). It offers a balanced array of amino acids, including significant levels of sulfur-containing amino acids and cysteine (Newkirk et al., 2003). Additionally, its low glucosinolate content makes it a suitable protein supplement for a variety of agricultural animals (Paula et al., 2018). Canola seed, in contrast to other oil seeds, has a tough seed coat that resists degradation in the rumen and small intestine, unless processed using some methods such as crushing or heating to facilitate its digestion (Kenuelly et al., 1987, Rinne et al., 2015, Negawoldes, 2018). The application of dry heat weakens the seed coat of the whole canola seed, increases the degree of ruminal escape of the protein fraction, and protects the long-chain FA from ruminal microbial biohydrogenation, while promoting its enzymatic digestion in the small intestine. Heat treatment of canola meal (CM) at 127°C increased the amount of ruminally undegradable protein (Micek et al., 2019). It was found that heat treatment enhanced the amount of rumen escape protein in the lower gastrointestinal tract by more than 30% (Nia and Ingalls, 1992). This can allow to include higher levels of canola seed in ruminant rations without affecting the digestion rate (Deacon et al., 1988) The high rumen degradability of canola meal prevents it from being used as a protein source for ruminants. This reduced the rumen bypass protein, which is necessary for high-yielding ruminants, as well as the ability of the rumen bacteria to use nitrogen (Wright et al., 2005; Broderick et al., 2016). Protection of protein from being broken down by rumen microbes using heat treatment boosted the post-ruminal amino acid supply, which was reflected in animal performance (Yu et al., 2005). Additionally, toasting or heating the canola meal at 105°C–110°C eliminated 40% of the glucosinolate content, reduced the meal toxicity, improved the animal performance, and increased the meal inclusion rates in the diets (Newkirk, 2002). The hypothesis of this study was that the tough seed coat of the whole canola seed could serve as a natural capsule for the administration of unsaturated FA post-ruminally. To preserve the majority of the whole canola seed from degrading by ruminal digestion, heat treatment should be mild enough to make the seed’s contents accessible to intestinal enzymatic degradation and absorption, and to prevent the rumen microbial degradation of the canola meal protein. Therefore, the objective of this study was to evaluate the impact of heat treatment of canola seed and its meal on ruminal degradation, ruminal biohydrogenation of unsaturated FA, and ruminal fermentation using the rumen simulation technique. Materials and MethodsHeat treatment procedureWhole canola seed and its meal were heated in a preheated oven at 127°C for 15 minutes. No moisture was added during the heating process. Afterward, the heated canola seed and its meal were allowed to cool at ambient temperature and then stored in plastic bags. Degradability trialsFour degradability trials were conducted using the rumen simulation technique (Rusitec) as designated by Czerkawski and Breckenridge (1977) to determine the degradation rate and rumen parameters for the different experimental diets. Four experimental rations were prepared, each ration included dietary canola seed or canola meal, Diet 1: untreated whole canola seed (UWCS), Diet 2: Heated whole canola seed (HWCS) at 127°C for 15 minutes, Diet 3: untreated canola meal (UCM), and Diet 4: Heated canola meal (HCM) at 127°C for 15 minutes. The experiment was conducted in four runs, each run with four treatments. The rations were fed to the fermentation vessels as a basic diet consisting of a concentrate mixture and chopped grass hay at 70% and 30%, respectively. Canola seed and its meal were added at a rate of 22% in the concentrate mixture. In each trial, all vessels received the same daily rations. The ingredients composition of the concentrate mixture was 57.2% maize, 18.0% wheat bran, 22.0% canola seed or meal, and 2.8% minerals and vitamins premix. The proximate analyses and FA profile of the total mixed rations supplied to the fermentation vessels are shown in Table 1. Also, the chemical analysis and FA profile of untreated and heated whole canola seed or its meal are presented in Table 2. These chemical analyses were carried out on three replicates for each sample of mixed ration or the used ingredients. Table 1. Chemical composition and fatty acids profile of the total mixed rations supplied to fermentation vessels (%, on DM basis).

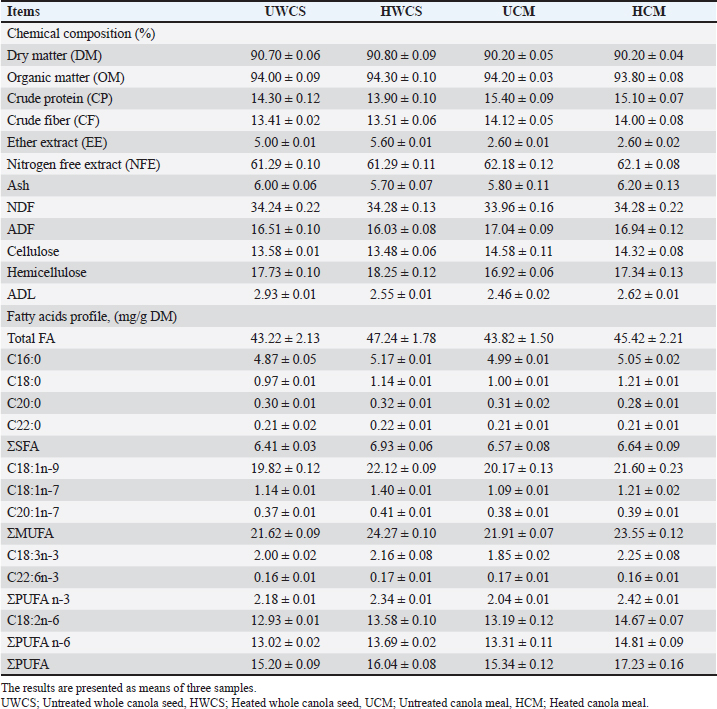

Table 2. Chemical composition and fatty acids profile of untreated and heat-treated canola seed or meal (%, on DM basis).

General incubation procedureThe complete unit of Rusitec consisted of four vessels with a nominal volume of 800 ml each. Inocula for fermentation vessels were obtained from the rumen of three fistulated adult male sheep. These rams were fed the same experimental diet for 1 month before the inocula was taken. Fermentation inocula (solid and liquid) were collected immediately from the rumen of the three rams and then maintained at 39°C. Within 1 hour, the incula was combined and filtered through three layers of cheesecloth before being delivered to the Rusitec system. Each vessel of Rusitec received 400 ml of filtered rumen liquid and 200 ml of synthetic saliva on the first day of the experiment (McDougall, 1948). About 80 g of squeezed particulate rumen materials were weighed and put inside a nylon sack (pore size of 100 µm), then added to the feed container in each vessel along with a bag of the experimental feed. Fermentation units were put in a water bath that was kept at 39°C. After 24 hours, the rumen solid inoculum bag was changed with a bag containing the experimental feed. On subsequent days, a fresh bag of experimental feed was substituted for the bag that had been found in each vessel for the previous 2 days. As a result, two bags were found at all times, and one was taken out daily and incubated for 48 hours. Each nylon bag contained 10.5 g of concentrate mixture and 4.5 g of grass hay as a fed basis. The flow of artificial saliva (pH 7.4) was constantly pumped into the fermentation units at a rate of 700–750 ml-1 using a peristaltic pump. Sampling, measurements, and analysesThe experiment at Rusitec continued for 14 days; the first 7 days as an adaption period and the following 7 days were spent collecting samples. For daily measurements of short-chain FA [volatile fatty acids (VFAs)] and ammonia nitrogen, before changing the bag with feed, one fluid sample was obtained from each vessel. The pH and redox potentials (for control of anaerobic conditions) of the rumen fluid were measured immediately with a pH meter (electrodes inlab501, Mettler-Toledo, Urdorf, Switzerland). During the collection period, the gas generated was captured in rubber bags to measure the total gas volume by the corresponding replacement of water. The undigested feed remnants in the feeding bags were cleaned and dried at 50°C for 24 hours. According to Bartels (1991), a spectrophotometer was used to determine the amount of ammonia in the ruminal fluid. The short-chain fatty acids VFA in the rumen fluid were determined as described by Kroismayr and Sehm (2007) using a gas chromatography instrument (Carlo Erba 5000, Milan, Italy). The chemical analysis of feeds and feed residues (undegradable feed samples) was carried out according to the procedures of the Association of Official Analytical Chemists (AOAC, 2019) using duplicate samples. According to Goering and Van Soest (1991), neutral detergent fiber (NDF), acid detergent fiber (ADF), and acid detergent lignin (ADL) were measured. The rumen degradation of nutrients after 48 hours of incubation was calculated by expressing the difference between the content of nutrients in both feed and feed residue as a percentage of its fermented feed. The long-chain fatty acids were measured in samples of feeds and feed residues using gas chromatography (HP 5890). Fatty acids methyl esters were analyzed using a GC system (HP 5890; Hewlett-Packard, Pennsylvania, USA). The separation employed a Supelco column (supelcowax 10.3 m length × 0.32 mm ID, 0.25 µm film) with hydrogen as a carrier gas at a flow rate of 2 ml/minute (head pressure 60 kPa). The extent of FA biohydrogenation of the total diet in the rumen was measured according to Loor et al. (2004). The biohydrogenation % of long-chain fatty acids in rumen = [(intake of fatty acid—residual feed fatty acid)/intake of fatty acid] × 100. Statistical analysisThe data for nutrient degradability, fatty acid biohydrogenation, and rumen fermentation kinetics using SAS’s PROC MIXED (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). A completely randomized block design was employed, treating each experimental run as a random block and each vessel as an independent experimental unit. Our statistical model accounted for the effects of heat treatment, canola form (either seed or meal), and their interaction. In this framework, the vessel nested within each treatment was considered a random effect, while the treatment itself was fixed. For the repeated measures, we evaluated two covariance structures— compound symmetry and an auto-regressive model (AR(1))—and selected the one with the lowest Akaike Information Criterion. When the F-test indicated significance (p < 0.05), we used the Tukey range test to compare the means. Results are reported as means ± SEM, and any F-value with a probability of less than 0.05 was considered as significant. The overall model was expressed as Yij = μ + Ti + eij, where Yij represents each observation for treatment i (with i ranging from 1 to 4), μ is the overall mean, Ti is the treatment effect (UWCS, HWCS, UCM, and HCM), and eij is the experimental error. ResultsEffect of heat treatment on the chemical composition of canola seed and its mealThe chemical analysis and fatty acids profile of untreated and heated whole canola seed or its meal on dry matter (DM) basis are shown in Table 2. The whole canola seed showed greater ether extract content than the canola meal. However, the crude protein content and nitrogen-free extract (NFE) were greater for the canola meal than those of the whole canola seed. Heating of whole canola seed tended to decrease the crude fibre (CF) with a slight increase in DM, nitrogen-free extract, and cellulose contents when compared to WCS. Rumen degradability of nutrientsThe average values of nutrient degradability in vitro are shown in Table 3. The degradability of DM, organic matter (OM), CP, EE, NFE, NDF, and hemicellulose was significantly (p < 0.05) lower in the heat-treated whole canola seed in comparison to the untreated one. Heat treatment of whole canola seed (HWCS) decreased significantly (p < 0.05) the degradability of DM, OM, CP, EE, NFE, NDF, and hemicellulose. No significant (p > 0.05) differences were found between the heat-treated CM and untreated one for all nutrients’ degradability, except for CP and EE, which were decreased (p < 0.05) in the heated CM. Also, the degradability of CF was decreased by about 29.15% in the heated CM when compared to the untreated one. The most obvious result was the decrease in the crude protein degradability by heat treatments of both whole canola seed and its meal. Moreover, it was observed that the ether extract degradability was affected (p < 0.05) by the form of canola. Table 3. Effect of heat treatment of canola seed and its meal on nutrients degradability using rumen simulation technique (Rusitec).

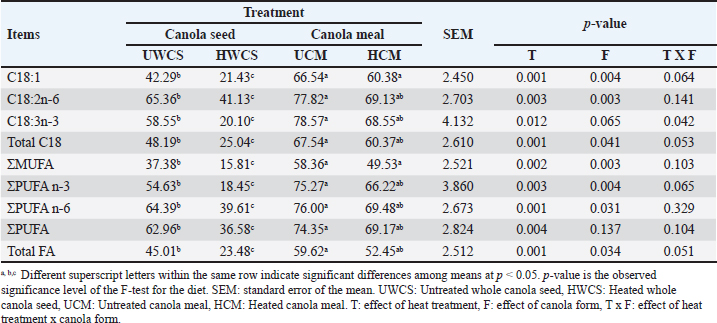

Rumen biohydrogenation (BH) of fatty acidsApparent biohydrogenation of individual C18, total C18, monounsaturated fatty acid (MUFA), polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA), and total long-chain fatty acids (LCFAs) are shown in Table 4. Heating the whole canola seed decreased significantly (p < 0.05) the BH of C18:1, C18:2, C18:3, total C18, MUFA, PUFA, and total LCFA in the rumen when compared to the untreated whole canola seed. However, heat treatment of the canola meal did not show any significant (p > 0.05) effect on the BH of fatty acids when compared to the untreated canola meal. Nevertheless, it was noticed a significant effect (p < 0.05) of canola form on the rumen biohydrogenation of long-chain fatty acids. Table 4. Effect of heat treatment of canola seed and its meal on rumen biohydrogenation of long chain fatty acids using rumen simulation technique (Rusitec).

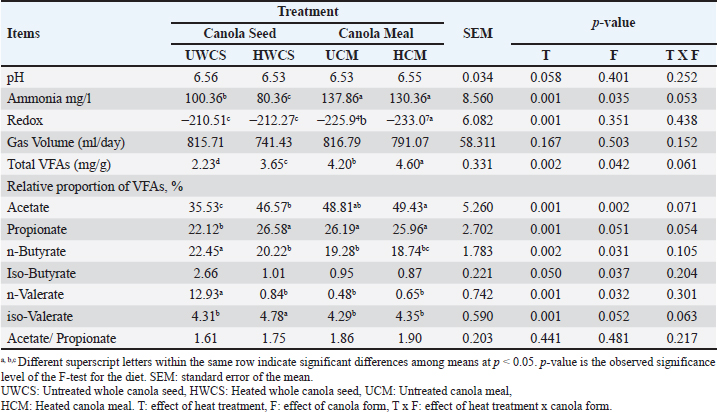

Rumen fermentationThere were no significant (p > 0.05) differences in the average ruminal pH values among the different groups (Table 5). The ruminal ammonia concentration was significantly (p < 0.05) higher in the untreated whole canola seed (100.36 mg/l) and its meal (137.87 mg/l) in comparison to the heat-treated seed (80.36 mg/l) and meal (130.36 mg/l). Rumen redox potential (Eh) was significantly (p < 0.05) higher in the ratio containing UCM than in that containing UWCS (–130.36 vs. –210.51). Similarly, heat treatment of HCM increased significantly (p < 0.05) the Eh when compared to the UCM (–233.07 vs. –225.94). However, no significant (p > 0.05) difference was found between HWCS and UWCS. The amount of gas production from all treatments tended to be similar without any significant differences. The concentration of total VFA, acetate, and propionate were significantly (p < 0.05) higher in the ration containing UCM than that containing UWCS. However, the proportions of n-butyrate, iso-butyrate, and n-valerate were significantly (p < 0.05) lower in UCM than in UWCS. Heat treatment of whole canola seed or its meal increased significantly (p < 0.05) the total VFA in the rumen fluid when compared to the untreated treatments. The proportions of acetate, propionate, and iso-valerate were increased, whereas these of n-butyrate, iso-butyrate, and n-valerate were decreased, in the heated WCS when compared to the untreated canola seed. No major differences were found between the heated and untreated canola meal for the individual proportions of fatty acids. Moreover, the form of canola influenced (p < 0.05) the rumen ammonia concentration as well as total and individual volatile fatty acids (VFAs) levels. Table 5. Effect of heat treatment of canola seed and its meal on rumen kinetics using rumen simulation technique (Rusitec).

DiscussionEffect of heat treatment on the chemical composition of canola seed and its mealThe chemical composition of untreated and treated canola seed and its meal are confirmed by the findings of earlier studies (Bell, 1993; Leupp et al., 2006; Ebrahimi et al., 2009). Newkirk (2002) attributed the differences in the chemical composition of canola seed and the quality of its meal to different seed genotypes and growing conditions. The higher NDF content of canola meal may be due to the seed coat present in the bran, which decreased the energy content of canola meal (Bell, 1993). Heat-treated whole canola seed or its meal are used in a wide range in Egypt, because it is an easy and economic method. Because canola protein is more easily denatured by heat than soybean protein (Lindberg et al., 1982), canola seed and its meal was heated at 127°C as an optimum temperature, as previously described in some publications such as Mir et al. (1984) and Tymchuk et al. (1998). Heating of whole canola seed and its meal at 127°C for 15 minutes had no effect on the crude protein content and fatty acids profile, because the heat treatment used in the present study was not sufficient to damage the canola seed protein and fatty acids (Tymchuk et al., 1998). The fatty acids profile of untreated or heat-treated canola seed and its meal in this study was similar to that found in the previous studies (Aldrich et al., 1997; Khorasani and Kennelly, 1998; Tymchuk et al., 1998). Rumen degradability of nutrientsThe findings of this study revealed that the degradability rate of the whole canola seeds in the rumen was lower. This was probably caused by the tough pericarp that surrounds the seed, but it could be digested in the lower gut. As stated by Bell (1993), the weight of the WCS hull accounts for 16%; it primarily consists of fiber (about 80% NDF, 67% ADF, and 18.5% lignin), which is mostly indigestible. The decreased nutrient degradability of WCS in the present study could be clarified by the fibrous material’s capacity, to maintain the integrity of WCS, which could limit the ruminal degradation. It seems that even if WCS was not entirely available for rumen degradation, mastication could aid in destroying the seed’s integrity and facilitating the attack by rumen microorganisms. Previous studies attributed the lower total tract OM digestibility of whole canola seed to the poor seed coat’s digestibility (Hussein et al., 1995). Moreover, the positive effect of feeding unprocessed whole oilseeds may be related to the diminished effects of extra fat on the digestibility of other feed components in the rumen, because the seed coat is thought to shield the oil from the ruminal metabolism (Baldwin and Allison, 1983). It could be noticed that the cell wall degradation tended to be lower in UWCS than in other diets. The resistance of UWCS against ruminal microbial degradation may be explained by the lower degradation of NDF and ADF (Hussein et al., 1996a). However, the untreated canola meal was rapidly degraded in the rumen and inadequate usage by the rumen bacteria, resulting in a small rumen bypass protein fraction reaching the small intestine (Sekali et al., 2020). In the present study, the heat treatment at 127°C for 15 minutes was more effective on the nutrient degradability of whole canola seed and its meal. Heat treatment of whole seeds and meals can change the physical structure of the fat conglomerates (Emanuelson et al., 1991). This might increase the amount of undegradable protein in the rumen and reduce the detrimental effects of fat on the digestion of rumen fiber or organic matter. Heat treatment decreased the proteins’ susceptibility to ruminal degradation by reducing their solubility and creating cross-links among peptide chains, carbohydrates, and both of them (Deacon et al., 1988). Mir et al. (1984) found that heating of canola meal protein to 110°C for 2 hours or to 120°C for 20 minutes reduced its rumen degradability. Furthermore, the ruminal degradability of rapeseed protein was reduced by about 18% and 52% when heated to 150°C and 200°C, respectively (Lindberg et al.,1982). McKinnon et al. (1995) stated that heating of canola meal at 125°C for 30 minutes enhanced the availability of dietary protein for digestion in the small intestine. Similarly, Mustafa et al. (2011) reported that heating of canola meal at 125°C for 10–30 minutes was an effective way to decrease the ruminal degradability of the protein without impairing the intestinal protein digestibility. Moreover, the form of canola affected the ether extract degradability, as the fat content in the canola seed is higher than that in the meal. Consequently, the rumen degredability rate of fat in the seed was found to be different than in the meal (Emanuelson et al., 1991; Sekali et al., 2020). Rumen biohydrogenation (BH) of fatty acidsIt is clear from this study that the heat treatment of canola seed increased the BH of long-chain fatty acids in the rumen. The lower BH of C18:1, C18:2, and C18:3 in UWCS when compared to the heat-treated CM could be due to the fact that it is difficult to weaken the seed coat, because of the high lignin and tannins content but maintaining some protection of LCFA in WCS against ruminal BH. This is the first step in modifying the FA composition of meat and milk produced by ruminants using natural dietary manipulation. Aldrich et al. (1997) reported that feeding whole oilseeds was an important method to minimize the rumen BH since the seed cover prevents the rumen microorganisms from accessing the unsaturated FA. Although whole seeds protect the unsaturated fatty acids from the ruminal BH, the seed may stay intact during passage through the small intestine. This resulted in a decrease in the digestibility of fatty acids (Aldrich et al., 1997). The significantly higher rumen BH of unsaturated FA in the untreated canola seed when compared to the treated one may be attributed to that the heat weakened the seed coat of canola and reduced the fat availability to rumen microorganisms, because the ruminal BH can only occur on free FA and not on FA in triacylglycerol (Hawke and Silcock, 1969). Previous investigations have demonstrated that triacylglycerols were rapidly lipolysed in the rumen (Beam et al., 2000). The cellulolytic bacterium Butyrivibrio fibrisolvens is one of the most significant bacteria for BH (Polan et al., 1964), resulting in the BH of FA may require a similar lag time to the degradation of fibre in situ. In our Rusitec experiment, the grass hay was incubated in the fermentation units and supplied with cellulolytic bacteria. The rumen BH of fatty acids in HCM tended to be lower than UCM, but was not significant. The large variations of BH could be related to the experimental conditions, because the BH in vitro depends on the substrate starch, nitrogen content, pH, and particle size (Van Nevel Demeyer,1996; Gerson et al., 1988 Click or tap here to enter text.). Moreover, the rumen biohydrogenation of fatty acids was influenced by the form of canola (seed or meal) as reported by Aldrich et al. (1997). Rumen fermentationThe general range of rumen pH is within 5.8–6.8 (Mertens, 1979), which is consistent with the findings of this study. The results of the present study demonstrated that the heat treatment of canola seed decreased the rumen ammonia concentration. Ammonia production in the rumen is a result of direct protein degradation by the microbial proteases (Parker et al., 1995). The higher ammonia concentration in the rumen fluid of the untreated whole canola seed or meal could be attributed to the greater degradability of dietary protein in these feeds (Emanuelson et al., 1991). Heat treatment of WCS affected the seed coats. This may delay the exposure of the seed content for microbial fermentation, which causes asynchrony between the released energy and the release of NH3 in the rumen. Similar results were found by Mabjeesh et al. (1999) who reported that the heat treatment of whole cottonseed increased the ammonia nitrogen concentration when compared with diets containing untreated whole cottonseed. Understanding the microbiological activity and dynamics of fermentation can be based on the measurement of pH and redox potential in the rumen content (Broberg, 1957). The redox potential values for all treatments were on average of -150–-260 mV for sheep (Barry et al., 1977). The heat treatment of canola seed enhanced the availability of polyunsaturated oil to the rumen microorganisms (Hussein et al., 1996b). According to previous studies, polyunsaturated oils had a positive impact on the yield of microbial proteins (Broudiscou et al., 1994); but it was found to have a negative effect in other research (Czerkawski et al., 1975). The exact way in which polyunsaturated dietary oils influence rumen metabolism is still not fully understood. Devendra and Lewis (1974) offered four possible explanations: first, oil might physically coat the fibers; second, the formation of insoluble soaps could lead to a calcium deficiency; third, these oils might directly inhibit the activity of rumen microbes; and finally, they could alter the microbial community through a toxic effect. Supporting this, research on lipid metabolism in the rumen shows that canola seed oil is rapidly broken down, with a significant portion of its polyunsaturated fatty acids being hydrogenated by rumen microorganisms into less harmful compounds like stearic acid (Scollan et al., 2001). In short, the observed toxicity of canola seed oil appears to be closely linked to this rapid microbial processing and the resulting shifts in the microbial population. Gas production tended to be similar in all treatments. Heat treatment of canola seed maximizes the availability of fat and polyunsaturated fatty acids in the rumen, and consequently increased the FA biohydrogenation in HWCS by the rumen microorganism. Beauchemin et al. (2011) reported that the FA profile of fats may have a little effect on CH4 emissions. Fatty acids are toxic to gram-positive bacteria, whereas gram-negative bacteria are less sensitive to fatty acids at the same concentration (Maczulak et al., 1981). Furthermore, leaving the seed coat intact for the WCS treatment could prevent this toxicity. These results agree with the findings reported by Spears (1996) who found that the fatty acids appear to be the most promising dietary substitute for the synthetic methane inhibitors. Heat treatment of canola seeds produced a slow release of unsaturated fatty acids, minimizing the detrimental effects in the rumen function and production of VFA (Hussein et al., 1995). Because dietary fat contributes directly and indirectly to the formation of ruminal VFA, supplemental fat in the ruminant’s diet is required. In the rumen, microbial lipolytic enzymes can cause rapid and extensive hydrolysis of the ester bonds of dietary fatty acyl glycerol to produce glycerol and free fatty acids (Jenkins, 1993). Following that, Nagaraja (1997) explained that rumen microorganisms could convert glycerol into VFAs. Furthermore, Khorasani et al. (1992) observed that the differences in VFA production reported in studies using dietary fat sources might stem from factors such as the amount of fat included, the saturation level of the fatty acids, the forage-to-concentrate ratio, the type of forage or grain used, as well as variations in the overall diet and among the animals themselves. Interestingly, in our study, a slight improvement of fiber degradation with heat treatment of canola seed was found when compared to UWCS, which may explain the higher proportion of total VFA, acetate, and propionate. The acetate-to-propionate ratio showed no significant differences across the treatments, indicating that the inclusion of canola seed in its various forms did not disrupt the typical rumen fermentation processes or digestion. This suggests that the treatments preserved the normal functioning of rumen fermentation. Khorasani et al. (1992) found insignificant differences in the acetate: propionate ratio, indicating similar fermentability for the dietary treatments. In the present study, the obtained findings exhibited that the rumen ammonia level as well as total and individual VFAs rates were affected by the canola form either seed or meal. The same findings were reported by previous studies (Emanuelson et al., 1991; Hussein et al., 1995). ConclusionThe obtained results indicate that the heat treatment of whole canola seed or its meal at 127°C improved the rumen escape of nutrients, especially for the dietary protein and unsaturated fatty acids. In addition, heating of canola seed and its meal enhanced the rumen fermentation parameters. Ruminal biohydrogenation of unsaturated fatty acids was decreased with heat treatment of whole canola seed. However, the heat treatment of canola meal failed to induce any change in the ruminal FA biohydrogenation. Therefore, it can be recommended to make heat treatment of whole canola seed or its meal in order to increase the rumen bypass protein percentage and unsaturated fatty acids, which are essential in improving the production of ruminant animals. In vitro methods are useful screening tools, but the results need to be verified in vivo to confirm the direct recommendations for feeding practices. Within the animal, there are many functions that cannot be mimicked by the in vitro system, such as the effects on intake and rate of passage from the rumen. AcknowledgmentsThis work was supported by the Deanship of Scientific Research, Vice Presidency for Graduate Studies and Scientific Research, King Faisal University, Saudi Arabia (Grant No. KFU251623). Conflict of interestThe authors declare that there is no conflict of interest. Ethical approvalThis study was conducted according to the ethical guidelines of King Faisal University, Saudi Arabia. Author’s contributionAll authors shared in conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, project administration, resources, software, supervision, validation, visualization, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing. Data availabilityAll data are included within the manuscript. ReferencesAldrich, C.G., Merchen, N.R., Drackley, J.K., Gonzalez, S.S., Fahey Jr, G.C. and Berger, L.L. 1997. The effects of chemical treatment of whole canola seed on lipid and protein digestion by steers. Anim. Sci. J. 75(2), 502–511. AOAC. 2019. Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC International. 18th ed. In: Ed., Latimer, G.W. Washington, DC: Oxford University Press Oxford; doi: 10.1093/9780197610138.001.0001 Baldwin, R.L. and Allison, M.J. 1983. Rumen Metabolism. J. Anim. Sci. 57, 461–77. Barry, T.N., Thompson, A. and Armstrong, D.G. 1977. Rumen fermentation studies on two contrasting diets. 1. Some characteristics of the in vivo fermentation, with special reference to the composition of the gas phase, oxidation/reduction state and volatile fatty acid proportions. J. Agric. Sci. 89(1), 183–195; doi: 10.1017/S0021859600027362 Bartels, U. 1991. The enzymatic determination of ammonium in precipitation water. CLB Chem. Lab. Biotechnol. 42, 377–382. Beam, T.M., Jenkins, T.C., Moate, P.J., Kohn, R.A. and Palmquist, D.L. 2000. Effects of amount and source of fat on the rates of lipolysis and biohydrogenation of fatty acids in ruminal contents. J. Dairy Sci. 83(11), 2564–2573; doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(00)75149-6 Beauchemin, K.A., McGinn, S.M. and Petit, H.V. 2011. Methane abatement strategies for cattle: lipid supplementation of diets. Can. J. Anim. Sci. 87, 431–440; doi: 10.4141/CJAS07011 Bell, J.M. 1993. Factors affecting the nutritional value of canola meal: a review. Can. J. Anim. Sci. 73(4), 689–697; doi: 10.4141/cjas93-075 Broberg, G. 1957. Oxygen’s significance for the ruminal flora as illustrated by measuring the redox potential in rumen contents. A provisional announcement. Nord. Vet. Med. 9, 57–60. Broderick, G.A., Colombini, S., Costa, S., Karsli, M.A. and Faciola, A.P. 2016. Chemical and ruminal in vitro evaluation of Canadian canola meals produced over 4 years. J. Dairy Sci. 99(10), 7956–7970; doi: 10.3168/jds.2016-11000 Broudiscou, L., Pochet, S. and Poncet, C. 1994. Effect of linseed oil supplementation on feed degradation and microbial synthesis in the rumen of ciliate-free and refaunated sheep. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 49(3-4), 189–202; doi: 10.1016/0377-8401(94)90045-0 C.O.P.A. 1998. Trading rules, 1998-99. Winipeg, MB: Canadian Oilseed Processors Association. Czerkawski, J.W. and Breckenridge, G. 1977. Design and development of a long-term rumen simulation technique (Rusitec). Br. J. Nutr. 38(3), 371–384; doi: 10.1079/bjn19770102 Czerkawski, J.W., Christie, W.W., Breckenridge, G. and Hunter, M.L. 1975. Changes in the rumen metabolism of sheep given increasing amounts of linseed oil in their diet. Br. J. Nutr. 34(1), 25–44; doi: 10.1017/s0007114575000074 Deacon, M.A., De Boer, G. and Kennelly, J.J. 1988. Influence of Jet-Sploding® and extrusion on ruminal and intestinal disappearance of canola and soybeans. J. Dairy Sci. 71(3), 745–753; doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(88)79614-9 Delbecchi, L., Ahnadi, C.E., Kennelly, J.J. and Lacasse, P. 2001. Milk fatty acid composition and mammary lipid metabolism in Holstein cows fed protected or unprotected canola seeds. J. Dairy Sci. 84(6), 1375–1381; doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(01)70168-3 Devendra, C. and Lewis, D. 1974. The interaction between dietary lipids and fibre in the sheep 2. Digestibility studies. Anim. Sci. 19(1), 67–76; doi: 10.1017/S0003356100022583 Ebrahimi, S.R., Nikkhah, A., Sadeghi, A.A. and Raisali, G. 2009. Chemical composition, secondary compounds, ruminal degradation and in vitro crude protein digestibility of gamma irradiated canola seed. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 151(3-4), 184–193; doi: 10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2009.01.014 Emanuelson, M., Murphy, M. and Lindberg, J.E. 1991. Effects of heat-treated and untreated full-fat rapeseed and tallow on rumen metabolism, digestibility, milk composition and milk yield in lactating cows. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 34(3-4), 291–309. Gerson, T., King, A.S.D., Kelly, K.E. and Kelly, W.J. 1988. Influence of particle size and surface area on in vitro rates of gas production, lipolysis of triacylglycerol and hydrogenation of linoleic acid by sheep rumen digesta or Ruminococcus flavefaciens. J. Agric. Sci. 110(1), 31–37; doi: 10.1017/S002185960007965X Goering, H.K. and Van Soest, P.J. 1991. Forage fiber analysis (apparatus, reagents, procedures, and some application). Agric. Handbook 379-ARS., Washington, DC: USDA. Hawke, J.C. and Silcock, W.R. 1969. Lipolysis and hydrogenation in the rumen. Biochem. J. 112(1), 131; doi: 10.1042/bj1120131 Hussein, H.S., Merchen, N.R. and Fahey Jr, G.C. 1995. Effects of forage level and canola seed supplementation on site and extent of digestion of organic matter, carbohydrates, and energy by steers. J. Anim. Sci. 73(8), 2458–2468; doi: 10.2527/1995.7382458x Hussein, H.S., Merchen, N.R. and Fahey Jr, G.C. 1996a. Effects of chemical treatment of whole canola seed on digestion of long-chain fatty acids by steers fed high or low forage diets. J. Dairy Sci. 79(1), 87–97; doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(96)76338-5 Hussein, H.S., Merchen, N.R. and Fahey Jr, G.C. 1996b. Effects of forage percentage and canola seed on ruminal protein metabolism and duodenal flows of amino acids in steers. J. Dairy Sci. 79(1), 98–104; doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(96)76339-7 Jenkins, T.C. 1993. Lipid metabolism in the rumen. J. Dairy Sci. 76(12), 3851–3863; doi: 10.3168/jds. S0022-0302(93)77727-9 Kenuelly, J.J., Deacon, M.A. and Deboer, G. 1987. Enhancement of the nutritive value of full-fat canola seed for ruminants. Roc. 7th Int. Refereed Congr. Poznan, Poland: 71692. Khorasani, G.R., De Boer, G., Robinson, P.H. and Kennelly, J.J. 1992. Effect of canola fat on ruminal and total tract digestion, plasma hormones, and metabolites in lactating dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 75(2), 492–501; doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(92)77786-8 Khorasani, G.R. and Kennelly, J.J. 1998. Effect of added dietary fat on performance, rumen characteristics, and plasma metabolites of midlactation dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 81(9), 2459–2468; doi: 10.3168/jds. S0022-0302(98)70137-7 Kroismayr, A. and Sehm, J. 2007. Effects of essential oils or Avilamycin on gut microbiology and blood parameters of weaned piglets. Bodenkultur 59(1-4), 111–120. Leupp, J.L., Lardy, G.P., Soto-Navarro, S.A., Bauer, M.L. and Caton, J.S. 2006. Effects of canola seed supplementation on intake, digestion, duodenal protein supply, and microbial efficiency in steers fed forage-based diets. J. Anim. Sci. 84(2), 499–507; doi: 10.2527/2006.842499x Lindberg, J.E., Soliman, H.S. and Sanne, S. 1982. study of the rumen degradability of untreated and heat treated rapeseed meal and of whole rapeseed, including a comparison between two nylon bags techniques. Swed. J. Agric. Res. 12, 83–88. Loor, J.J., Ueda, K., Ferlay, A., Chilliard, Y. and Doreau, M. 2004. Biohydrogenation, duodenal flow, and intestinal digestibility of trans fatty acids and conjugated linoleic acids in response to dietary forage: concentrate ratio and linseed oil in dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 87(8), 2472–2485; doi: 10.3168/ jds.S0022-0302(04)73372-X Mabjeesh, S.J., Bruckental, I. and Arieli, A. 1999. Heat-treated whole cottonseed: effect of dietary protein concentration on the performance and amino acid utilization by the mammary gland of dairy cows. J. Dairy Res. 66(1), 9–22; doi: 10.1017/ s0022029998003306 Maczulak, A.E., Dehority, B.A. and Palmquist, D.L. 1981. Effects of long-chain fatty acids on growth of rumen bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 42(5), 856–862; doi: 10.1128/aem.42.5.856-862.1981 McDougallm, E. 1984. Studies on ruminant saliva. 1. The composition and output of sheep’s saliva. Biochem J. 43(1), 99–109. McKinnon, J.J., Olubobokun, J.A., Mustafa, A., Cohen, R.D.H. and Christensen, D.A. 1995. Influence of dry heat treatment of canola meal on site and extent of nutrient disappearance in ruminants. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 56(3-4), 243–252; doi: 10.1016/0377-8401(95)00828-4 Mertens, D.R. 1979. Effects of buffers upon fiber digestion. In Regulation of acid-base balance. Eds., Hale, W.H. and Mehhardt, P. Piscataway, N J: Church & Dwight Company Inc., pp: 65–75. Micek, P., Słota, K. and Górka, P. 2019. Effect of heat treatment and heat treatment in combination with lignosulfonate on in situ rumen degradability of canola cake crude protein, lysine, and methionine. Can. J. Anim. Sci. 100(1), 165–174; doi: 10.1139/cjas-2018-0216 Mir, Z., MacLeod, G.K., Buchanan-Smith, J.G., Grieve, D.G. and Grovum, W.L. 1984. Methods for protecting soybean and canola proteins from degradation in the rumen. Can. J. Anim. Sci. 64(4), 855–865; doi: 10.4141/cjas84-099 Mustafa, A.F., Christensen, D.A., McKinnon, J.J. and Newkirk, R. 2011. Effects of stage of processing of canola seed on chemical composition and in vitro protein degradability of canola meal and intermediate products. Can. J. Anim. Sci. 80(1), 211–214; doi: 10.4141/A99-079 80:211–4 Nagaraja, T.G. 1997. Manipulation of ruminal fermentation. 2 ed. In: The rumen microbial ecosystem. Eds., Hobson, P.N. and Stewart, C.S. London, UK: Blackie Academic and professional, p: 521.Negawoldes, T.Y. 2018. Review on nutritional limitations and opportunities of using rapeseed meal and other rape seed by-products in animal feeding. J. Nutr. Health Food Eng. 8(1), 43–48; doi: 10.15406/jnhfe.2018.08.00254 Nia, S.M. and Ingalls, J.R. 1992. Effect of heating on canola meal protein degradation in the rumen and digestion in the lower gastrointestinal tract of steers. Canadian J. Ani. Sci. 72(1), 83–88. Newkirk, R.W. 2002. The effects of processing on the nutritional value of canola meal for broiler chickens. PhD thesis, Department of Animal and Poultry Science, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, CA. Newkirk, R.W., Classen, H.L., Scott, T.A. and Edney, M.J. 2003. The digestibility and content of amino acids in toasted and non-toasted canola meals. Can. J. Anim. Sci. 83(1), 131–139; doi: 10.4141/A02-028 Parker, D.S., Lomax, M.A., Seal, C.J. and Wilton, J.C. 1995. Metabolic implications of ammonia production in the ruminant. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 54(2), 549–563. Paula, E.M., Broderick, G.A., Danes, M.A.C., Lobos, N.E., Zanton, G.I. and Faciola, A.P. 2018. Effects of replacing soybean meal with canola meal or treated canola meal on ruminal digestion, omasal nutrient flow, and performance in lactating dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 101(1), 328–339; doi: 10.3168/jds.2017-13392 Polan, C.E., McNeill, J.J. and Tove, S.B. 1964. Biohydrogenation of unsaturated fatty acids by rumen bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 88(4), 1056–1064; doi: 10.1128/jb.88.4.1056-1064.1964 Rinne, M., Kuoppala, K., Ahvenjärvi, S. and Vanhatalo, A. 2015. Dairy cow responses to graded levels of rapeseed and soya bean expeller supplementation on a red clover/grass silage-based diet. J. Anim. 9(12), 1958–1969; doi: 10.1017/S1751731115001263 Scollan, N.D., Dhanoa, M.S., Choi, N.J., Maeng, W.J., Enser, M, and Wood, J.D. 2001. Biohydrogenation and digestion of long chain fatty acids in steers fed on different sources of lipid. J. Agric. Sci. 136(3), 345–355; doi: 10.1128/jb.88.4.1056-1064.1964 Sekali, M., Mlambo, V., Marume, U. and Mathuthu, M. 2020. Replacement of soybean meal with heat-treated canola meal in finishing diets of Meatmaster lambs: physiological and meat quality responses. Anim. 10(10), 1735; doi:10.3390/ani10101735 Spears, J.W. 1996. Beef nutrition in the 21st century. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 58(1-2), 29–35; doi: 10.1016/0377-8401(95)00871-3 Tymchuk, S.M., Khorasani, G.R. and Kennelly, J.J. 1998. Effect of feeding formaldehyde-and heat-treated oil seed on milk yield and milk composition. Can. J. Anim. Sci. 78(4), 693–700; doi: 10.4141/ A97-112 Van Nevel, C.J. and Demeyer, D.I. 1996. Influence of pH on lipolysis and biohydrogenation of soybean oil by rumen contents in vitro. Reprod. Nut. Dev. 36(1), 53–63; doi: 10.1051/rnd:19960105 Wright, C.F., Von Keyserlingk, M.A.G., Swift, M.L., Fisher, L.J., Shelford, J.A. and Dinn, N.E. 2005. Heat-and lignosulfonate-treated canola meal as a source of ruminal undegradable protein for lactating dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 88(1), 238–243; doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(05)72681-3 Yu, P., McKinnon, J.J., Soita, H.W., Christensen, C.R. and Christensen, D.A. 2005. Use of synchrotron-based FTIR microspectroscopy to determine protein secondary structures of raw and heat-treated brown and golden flaxseeds: a novel approach. Can. J. Anim. Sci. 85(4), 437–448; doi: 10.4141/A05-004 | ||

| How to Cite this Article |

| Pubmed Style Aleid MS, Abdel-raheem SM, Farghaly MM, Youssef IMI, Monzaly HMA, Hamada A, Shousha S, Abouamra WK. Effect of heat treatment of canola seed and its meal on nutrients degradability, ruminal fermentation, and ruminal biohydrogenation of unsaturated fatty acids using rumen simulation technique (Rusitec). Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(6): 2849-2860. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.54 Web Style Aleid MS, Abdel-raheem SM, Farghaly MM, Youssef IMI, Monzaly HMA, Hamada A, Shousha S, Abouamra WK. Effect of heat treatment of canola seed and its meal on nutrients degradability, ruminal fermentation, and ruminal biohydrogenation of unsaturated fatty acids using rumen simulation technique (Rusitec). https://www.openveterinaryjournal.com/?mno=254496 [Access: January 25, 2026]. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.54 AMA (American Medical Association) Style Aleid MS, Abdel-raheem SM, Farghaly MM, Youssef IMI, Monzaly HMA, Hamada A, Shousha S, Abouamra WK. Effect of heat treatment of canola seed and its meal on nutrients degradability, ruminal fermentation, and ruminal biohydrogenation of unsaturated fatty acids using rumen simulation technique (Rusitec). Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(6): 2849-2860. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.54 Vancouver/ICMJE Style Aleid MS, Abdel-raheem SM, Farghaly MM, Youssef IMI, Monzaly HMA, Hamada A, Shousha S, Abouamra WK. Effect of heat treatment of canola seed and its meal on nutrients degradability, ruminal fermentation, and ruminal biohydrogenation of unsaturated fatty acids using rumen simulation technique (Rusitec). Open Vet. J.. (2025), [cited January 25, 2026]; 15(6): 2849-2860. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.54 Harvard Style Aleid, M. S., Abdel-raheem, . S. M., Farghaly, . M. M., Youssef, . I. M. I., Monzaly, . H. M. A., Hamada, . A., Shousha, . S. & Abouamra, . W. K. (2025) Effect of heat treatment of canola seed and its meal on nutrients degradability, ruminal fermentation, and ruminal biohydrogenation of unsaturated fatty acids using rumen simulation technique (Rusitec). Open Vet. J., 15 (6), 2849-2860. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.54 Turabian Style Aleid, Mohammed Sami, Sherief M. Abdel-raheem, Mohsen M. Farghaly, Ibrahim M. I. Youssef, Hayam M. A. Monzaly, Alhosein Hamada, Saad Shousha, and Waleed K. Abouamra. 2025. Effect of heat treatment of canola seed and its meal on nutrients degradability, ruminal fermentation, and ruminal biohydrogenation of unsaturated fatty acids using rumen simulation technique (Rusitec). Open Veterinary Journal, 15 (6), 2849-2860. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.54 Chicago Style Aleid, Mohammed Sami, Sherief M. Abdel-raheem, Mohsen M. Farghaly, Ibrahim M. I. Youssef, Hayam M. A. Monzaly, Alhosein Hamada, Saad Shousha, and Waleed K. Abouamra. "Effect of heat treatment of canola seed and its meal on nutrients degradability, ruminal fermentation, and ruminal biohydrogenation of unsaturated fatty acids using rumen simulation technique (Rusitec)." Open Veterinary Journal 15 (2025), 2849-2860. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.54 MLA (The Modern Language Association) Style Aleid, Mohammed Sami, Sherief M. Abdel-raheem, Mohsen M. Farghaly, Ibrahim M. I. Youssef, Hayam M. A. Monzaly, Alhosein Hamada, Saad Shousha, and Waleed K. Abouamra. "Effect of heat treatment of canola seed and its meal on nutrients degradability, ruminal fermentation, and ruminal biohydrogenation of unsaturated fatty acids using rumen simulation technique (Rusitec)." Open Veterinary Journal 15.6 (2025), 2849-2860. Print. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.54 APA (American Psychological Association) Style Aleid, M. S., Abdel-raheem, . S. M., Farghaly, . M. M., Youssef, . I. M. I., Monzaly, . H. M. A., Hamada, . A., Shousha, . S. & Abouamra, . W. K. (2025) Effect of heat treatment of canola seed and its meal on nutrients degradability, ruminal fermentation, and ruminal biohydrogenation of unsaturated fatty acids using rumen simulation technique (Rusitec). Open Veterinary Journal, 15 (6), 2849-2860. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i6.54 |