| Research Article | ||

Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(9): 4146-4152 Open Veterinary Journal, (2025), Vol. 15(9): 4146-4152 Research Article Effect of fermented red bean extract (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) on spermatogenic cells in mice exposed to smokeElias Setyo Novanto1, Aswin Rafif Khairullah2, Budiarto Budiarto3, Tita Damayanti Lestari4*, Sri Pantja Madyawati4, Tatik Hernawati4, Kadek Rachmawati5, Imam Mustofa4, Siti Darodjah Rasad6, Ahmed Qasim Dawood7,8, Ginta Riady9, Wasito Wasito2, Riza Zainuddin Ahmad2, Bima Putra Pratama10 and Novia Chairuman111Profession Program of Veterinary Medicine, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Universitas Airlangga, Surabaya, Indonesia 2Research Center for Veterinary Science, National Research and Innovation Agency (BRIN), Bogor, Indonesia 3Division of Veterinary Public Health, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Universitas Airlangga, Surabaya, Indonesia 4Division of Veterinary Reproduction, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Universitas Airlangga, Surabaya, Indonesia 5Division of Basic Veterinary Medicine, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Universitas Airlangga, Surabaya, Indonesia 6Animal Husbandry Faculty, Universitas Padjadjaran, Sumedang, Indonesia 7Department of Veterinary Preclinical Sciences, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Universiti Putra Malaysia, Selangor, Malaysia 8Department of Physiology, Pharmacology, and Chemistry, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Al Shatra University, Al Shatra, Iraq 9Reproduction Laboratory, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Universitas Syiah Kuala, Banda Aceh, Indonesia 10Research Center for Agroindustry, National Research and Innovation Agency (BRIN), South Tangerang, Indonesia 11Research Center for Food Crops, National Research and Innovation Agency (BRIN), Bogor, Indonesia *Corresponding Author: Tita Damayanti Lestari. Division of Veterinary Reproduction, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Universitas Airlangga, Surabaya, Indonesia. Email: titadlestari [at] fkh.unair.ac.id Submitted: 23/06/2025 Revised: 13/08/2025 Accepted: 24/08/2025 Published: 30/09/2025 © 2025 Open Veterinary Journal

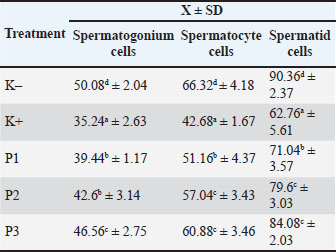

ABSTRACTBackground: Red beans are rich in bioactive compounds, such as flavonoids, anthocyanins, tannins, and polyphenols, which have high antioxidant activity and are believed to provide protection against testicular tissue exposure to toxic substances, including cigarette smoke. Aim: This study aims to scientifically analyze the effect of fermented red bean extract on the number of spermatogenic cells in male mice exposed to cigarette smoke. Methods: This experimental study included 25 mice. Group K (–) was administered 0.5 ml of 1% CMC-Na, group K (+) was administered 0.5 ml of 1% CMC-Na and exposed to cigarette smoke, and groups P1, P2, and P3 were administered fermented red bean extract (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) at doses of 26 mg/kgBW, 52 mg/kgBW, and 104 mg/kgBW, respectively, and exposed to cigarette smoke. Each group was given one cigarette per day for 36 days. Testicular histopathology preparations were made with hematoxylin and eosin staining and continued with spermatogenic cell counting. Data were analyzed using the one-way analysis of variance and continued with Duncan’s test (p < 0.05). Results: The results showed that the K(–) group had the highest number of spermatogenic cells, while the K(+) group had the lowest number of spermatogenic cells. The P2 group was the most effective method in maintaining the number of cells because the P2 group had a good number of cells even with a lower dose compared to the P3 group. Conclusion: This study concluded that the dose of 52 mg/kgBW has the best potential. Fermented red bean extract contains isoflavones that act as free radical scavengers by donating electrons to reactive oxygen species to stabilize the molecule. Keywords: Health risks, Red beans, Spermatogonium, Spermatocytes, Spermatids. IntroductionCigarette smoke contains harmful chemicals, such as nicotine, carbon monoxide, tar, and free radicals, which negatively impact both the reproductive and other organ systems in humans and animals (Cha et al., 2023). Cigarette smoke exposure is linked to notable decreases in male fertility through direct effects on testicular tissue, oxidative processes, and hormones (Dai et al., 2015). Long-term exposure to cigarette smoke damages the seminiferous tubules and interferes with spermatogenesis, the process by which germ cells in the testes develop into spermatozoa cells (Esakky and Moley, 2016). Spermatogenesis is a progressive biological process that begins with the division of spermatogonium cells, or early germ cells, followed by the differentiation of spermatocytes (the meiosis stage), and ultimately the development of mature spermatids that are prepared to transform into spermatozoa (Ibtisham et al., 2017). Stability of the microenvironment and integrity of the testicular tissue are critical components of this process. This, in turn, causes germ cells to undergo apoptosis and lowers spermatogenic cell numbers and caliber. The sharp decline in spermatogonia, spermatocytes, and spermatids immediately affects male fertility (Kimura et al., 2003). The application of natural chemicals derived from plants as defenses against harmful effects on the environment has grown significantly in recent years. Red beans (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) are a plant with a lot of promise. Red beans are a good source of bioactive substances with strong antioxidant properties, including flavonoids, anthocyanins, tannins, and polyphenols (Martínez-Alonso et al., 2022). Antioxidants can neutralize free radicals and shield cells from oxidative damage (Pham-Huy et al., 2008). As a result, these chemicals can shield testicular cells from harmful pollutants, such as cigarette smoke. A straightforward biotechnological procedure called fermentation can boost the nutritional content and bioavailability of a food ingredient (Siddiqui et al., 2023). The fermentation process in red beans boosts antioxidant content and transforms complicated phenolic chemicals into more readily absorbed and physiologically active forms (Martínez-Alonso et al., 2022). Thus, fermented red bean extract has a higher potential in providing a protective effect against tissue damage due to oxidative stress compared to non-fermented extract. In this study, male mice were used to evaluate the impact of cigarette smoke exposure on spermatogenic cells and determine the extent to which fermented red bean extract can provide protection against this damage. The observed parameters include the number of spermatogonia, spermatocytes, and spermatids, which are indicators of the spermatogenesis process. This study aims to scientifically analyze the effect of fermented red bean extract on the number of spermatogenic cells in male mice exposed to cigarette smoke. The findings of this study should be helpful in the creation of treatments or supplements based on natural ingredients to lessen reproductive abnormalities caused by exposure to harmful settings. Furthermore, this study may pave the way for the use of red beans as a functional dietary ingredient that promotes the health of male reproductive system. Materials and MethodsResearch designThis research was conducted from January 2023 to February 2023. The implementation of this research was carried out in three places. The first location was the Experimental Animal Cage Unit of the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Airlangga University, as a place for keeping and treating experimental animals. Fermented red bean extract was manufactured in the Division of Basic Veterinary Medicine, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Airlangga University. The histopathological preparations were manufactured and examined at the Pathology Laboratory of Airlangga University. The experimental animals used in this study were 2–3 months old male mice (Mus musculus) with a body weight of around 20–25 g, 25 of which had never been used in research. The sample used in this study was the testes of some male mice that were treated for 36 days. The mice were then sacrificed, and their testes were taken. Extraction processDried red beans (500 g) were cleaned and soaked in clean water for 8 hours at room temperature (27°C–30°C). After soaking, the red beans were steamed for 30 minutes until half-softened to facilitate the fermentation process. Fermentation was carried out in a sterile glass container with a lid (volume: 1 l) that had been sanitized using 70% alcohol. The fermentation process took place spontaneously (without starter culture inoculation) for 72 hours (3 days) at a controlled room temperature of 28°C–30°C and placed in a dark environment to avoid degradation of phenolic compounds due to light (De Luna et al., 2020). After fermentation, the fermented mixture is filtered using sterile gauze to separate the solid dregs from the fermentation liquid. The filtrate is then refiltered using the Whatman No. 1 filter paper with the help of vacuum filtration (Büchner funnel and laboratory vacuum pump) to obtain a clearer extract free of coarse particles. The filtered extract is then evaporated using a water bath at a temperature of 50°C, not 500°C (note: a temperature of 500°C is not suitable for liquid evaporation and can damage active compounds). The evaporation process is performed until a thick extract is obtained. The obtained extract is stored in a dark glass bottle at 4°C until ready for use for treating mice(Kurnijasanti and Candrarisna, 2019). Red bean extract dosageThe final doses of fermented red bean extract used in this study were 26 mg/kg BW, 52 mg/kg BW, and 104 mg/kg BW. These doses were determined based on a comparison of isoflavone content in fermented and non-fermented red bean extracts and a reference to previous literature (Collison, 2008; Martínez-Alonso et al., 2022; Novriadi et al., 2023). Treatment of the experimental animalsBefore the study, the mice were first adapted to homogeneous environmental conditions for 7 days. Homogeneous environments consist of cages, temperature, and food and drink provision. The cage base consisted of rice husks, pellets of feed, and drinking water that was given routinely in the morning and evening. The 25 mice were divided into five treatment groups with five mice each. The treatment groups were as follows: K–: A group of mice not exposed to cigarette smoke and given 1% CMC Na suspension. K+: A group of mice was exposed to cigarette smoke for 36 days and given 1% CMC Na suspension. P1: A group of mice was exposed to cigarette smoke for 36 days and given fermented red bean extract at a dose of 26 mg/kg body weight dissolved in 1% CMC Na and given orally. P2: A group of mice was exposed to cigarette smoke for 36 days and given fermented red bean extract at a dose of 52 mg/kg body weight dissolved in 1% CMC Na and given orally. P3: A group of mice was exposed to cigarette smoke for 36 days and given fermented red bean extract at a dose of 104 mg/kg body weight dissolved in 1% CMC Na and given orally. This study took 43 days. Adaptation was performed for 7 days, and treatment was performed for 36 days. Termination and samplingOn the 44th day, all treatment groups were terminated. Termination was carried out by cervical dislocation to perform abdominal cavity surgery to remove the testis organs. In taking testis samples, the scrotum was opened, and the testis organs were removed. Furthermore, the testes were washed with a physiological solution and stored in an organ pot containing 10% formalin solution to make histopathological preparations to see the picture of spermatogonium cells, spermatocytes, and spermatids in the seminiferous tubules (Rahma et al., 2021). Stages of histopathology preparationHistopathology preparations based on the method by Slaoui and Fiette (2011). The procedure for making histopathology preparations of testicular organs using routine or paraffin methods includes organ removal, fixation, trimming, dehydration, clearing, impregnation, sectioning, staining, and mounting. Number of spermatogonia, spermatocytes, and spermatidsThe number of spermatogonium cells, spermatocytes, and spermatids in five seminiferous tubules in one preparation was counted using a light microscope with a magnification of 400x and then counted using Optilab. The results and calculations of each seminiferous tubule in one preparation were added up, and the average was calculated. Data analysisThe data from the sum of spermatogonium cells, spermatocytes, and spermatids are presented in X±SD, to see the differences in treatment, analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used at a 5% confidence level. If there is a significant difference between treatments, the Duncan distance test is continued (5%). One-way ANOVA and Duncan distance test were conducted using SPSS version 21 for Windows. Ethical approvalThis research was approved by the Animal Ethics Commission, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Universitas Airlangga, Animal Care and Use Committee (ACUC), with certificate number 1.KEH.001.01.2023, dated 4 January 2023. ResultsBased on the results of the Duncan follow-up test (Table 1), the highest average number of spermatogonium cells was in the K– group of 50.08 ± 2.04, while the lowest average number of spermatogonium cells was in the K+ group, 35.24 ± 2.63. Groups P1, P2, and P3 were exposed to cigarette smoke and given red bean fermentation extract at doses of 26, 52, and 104 mg/kgBW/day. Group P3 had the highest number of spermatogonium cells with a number of cells of 46.56 ± 2.75, followed by group P2 with a number of cells of 42.6 ± 3.14, and group P1 had the lowest number of spermatogonium cells, 39.44 ± 1.17. Table 1. Mean and standard deviation of the number of spermatogonium cells, spermatocytes, and spermatids in male mice (Mus musculus) exposed to cigarette smoke and treated with fermented red bean extract (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) for 36 days, based on histological analysis under microscopy.

Next, the average number of spermatocyte cells was highest in the K-group at 66.32 ± 4.18, whereas the average number of spermatocyte cells was lowest in the K+ group at 42.68 ± 1.67. Groups P1, P2, and P3 were exposed to cigarette smoke and given red bean fermentation extract at doses of 26 mg/kgBW/day, 52 mg/kgBW/day, and 104 mg/kgBW/day. Group P3 had the highest number of spermatocyte cells with a number of cells of 60.88 ± 3.46, followed by group P2 with a number of cells of 57.04 ± 3.43, and group P1 showed the lowest number of spermatocyte cells of 51.16 ± 4.37. Next, the highest average number of spermatid cells was observed in the K-group at 90.36 ± 2.37, whereas the lowest average number of spermatid cells was observed in the K+ group at 62.76 ± 5.61. Groups P1, P2, P3 exposed to cigarette smoke and given red bean fermented extract at doses of 26 mg/kgBW/day, 52 mg/kgBW/day, and 104 mg/kgBW/day showed that group P3 had the highest number of spermatid cells with a number of cells of 84.08 ± 2.03, followed by group P2 with a number of cells of 79.6 ± 3.03 and group P1 showed the lowest number of spermatid cells of 71.04 ± 3.57. In line with these results, it can be seen in Figure 1 that the number of spermatogonia, spermatocyte, and spermatid cells in the K+ group decreased when compared to the K-group, which was not exposed to cigarette smoke exposure treatment. Meanwhile, groups P1, P2, and P3, which were given red bean fermentation extract, showed an increase in the number of spermatogonia, spermatocyte, and spermatid cells compared with the K– group, which was exposed to smoke but not given red bean fermentation extract (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Histopathological image of seminiferous tubule cells with 400x magnification in hematoxylin and eosin staining. Green arrows indicate spermatogonium cells, yellow arrows indicate spermatocytes, and blue arrows indicate spermatids. DiscussionHistopathological observation of the seminiferous tubules aims to determine the effect of administering fermented red bean extract (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) in maintaining the number of spermatogonium cells, spermatocytes, and spermatids in male mice (Mus musculus) exposed to smoke. Calculation of the average number of spermatogonium cells, spermatocytes, and spermatids shows that administering varying doses of fermented red bean extract as a preventive measure can maintain the number of spermatogonium cells, spermatocytes, and spermatids in mice exposed to cigarette smoke. Cigarette smoke that enters the body of mice has the potential to increase the levels of free radicals in the form of reactive oxygen species (ROS), such as superoxide (O2), hydroxyl radicals (OH), and peroxyl radicals (RO2) (Seo et al., 2023). Oxidative stress, which is caused by an excess of free radicals, damages the cell membrane first and then the cell itself (Chaudhary et al., 2023). Free radicals can covalently attach to cell membrane receptors or enzymes, altering the function of the membrane’s constituent parts (Petersen, 2017). Cell damage can impair normal cell activity by altering the shape of the membrane and deactivating membrane connections with enzymes or receptors (Ammendolia et al., 2021). Oxidative stress results from an imbalance between the body’s natural antioxidant capability and the quantity of free radicals present (Sharifi-Rad et al., 2020). Free radical-induced oxidative stress results in lipid peroxidation, which converts polyunsaturated fatty acids into lipid hydroperoxides (Ayala et al., 2014). Lipid peroxidation causes cell damage by disrupting cell membrane function and forming reactive aldehydes (Pizzimenti et al., 2013). Free radicals and spermatogenic cell membrane components, particularly lipids, react to cause lipid peroxidation, which disrupts ion transport, membrane permeability, and cell leakage because spermatogenic cell membranes lose their integrity and become more fluid (Wang et al., 2025). Cells lose their ability to operate when their membranes are damaged, which ultimately damages spermatogenic cells (Castro et al., 2025). Although ROS are physiologically significant for sperm function, ROS can be harmful to sperm at high concentrations. The sperm membrane is damaged by high levels of ROS that surpass antioxidants, which also lowers Leydig cell function (Sengupta et al., 2024). Smoking lowers testosterone hormone levels and impacts spermatogenesis (Osadchuk et al., 2023). A different study was conducted to determine how cigarette smoke affects the plasma testosterone levels and erectile function of rats exposed to cigarette smoke. The results showed that the testosterone levels in the experimental group were significantly lower than those in the control group, and the rats’ erectile function had also decreased (Park et al., 2012). The decline in testosterone levels indicates a problem with the hypothalamus’s ability to stimulate the release of sexual hormones (Hauger et al., 2022). ROS contributes to hormone release in physiological settings, but excessive ROS can prevent sexual hormone secretion (Darbandi et al., 2018). ROS can disrupt signaling pathways and are likely to have cytotoxic effects (An et al., 2024). The function of Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone in promoting the release of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH) hormones is inhibited when the signaling pathway is disrupted (Barabás et al., 2020). A disruption in the production of FSH and LH would result in an irregular spermatogenesis process in the testes’ seminiferous tubules (Oduwole et al., 2021). Based on the above explanation, the results conform to this study, where the positive control group (K+) had the smallest number of spermatogenic cells. Mice in the positive control group exposed to cigarette smoke without red bean fermentation extract had the lowest number of spermatogonia, spermatocytes, and spermatid cells compared with the other groups. Exposure to cigarette smoke causes the spermatogenesis process to not run normally. In addition to the rise in free radicals within the body, external antioxidants are required if the endogenous antioxidant capacity is not balanced with the quantity of free radicals (Martemucci et al., 2022). The body’s defensive mechanism against radical compounds has two parts: the preventative defense system and the defense system that breaks the free radical chain reactions. Primary antioxidants are responsible for stopping the free radical chain reaction, whereas secondary antioxidants are responsible for the preventative defense system (Chaudhary et al., 2023). Primary antioxidants are compounds that act as acceptors of free radicals and block the free radical mechanism in the oxidation process (Martemucci et al., 2022). This antioxidant can react with lipid radicals and transform them into a more stable state; it is also referred to as a chain-breaking antioxidant. Secondary antioxidants, also known as protective antioxidants, contribute to lowering the chain start rate in a variety of ways (Lobo et al., 2010). Metals are bound or their synthesis is disrupted in the preventative defense mechanism to prevent the creation of ROS complexes and free radicals (Afzal et al., 2023). Antioxidants inhibit free radical formation by providing new electrons to unpaired electrons, thereby reducing the reactive properties of free radicals (Lü et al., 2010). Antioxidant substances found in red beans, including flavonoids, phenolic acids, and anthocyanins, can scavenge free radicals and stop oxidative damage (Orak et al., 2015). Glycosides such as genistin, daidzin, and glycitin, which are conjugated by attaching to a single sugar molecule, make up the majority of isoflavones found in soybeans or soybean products (Delmonte and Rader, 2006). Fermentation increases the antioxidant activity of red beans. The bioactive compound isoflavone, which contains phenolic groups as one of the flavonoid groups, can act as an antioxidant and stop damage from free radicals by donating hydrogen ions and scavenging free radicals directly (Roy et al., 2022). According to reports, flavonoids can scavenge RO2, which will regenerate into organic hydroperoxides, and OH, which will regenerate into H2O (Treml and Šmejkal, 2016). More stable compounds are produced when hydroxyl and peroxyl radicals are regenerated. The isoflavone compounds of the flavonoid group can donate hydrogen to free radicals, resulting in stable, low-energy radicals derived from flavonoid compounds that have lost hydrogen atoms (Kasote et al., 2015). Red beans with isoflavones are a good source of primary antioxidants that can help break free radical chain reaction (Lobo et al., 2010). The administration of fermented red bean extract can result in the highest concentration of phenolic compounds and antioxidant activity (Alcázar-Valle et al., 2020). The results of the examination of the seminiferous tubules of mice showed an increase in the number of spermatogonium cells, spermatocytes, and spermatids in the group given red bean fermentation extract. The increase was seen in groups P1, P2, and P3, which were exposed to cigarette smoke at 1 cigarette/day and red bean fermentation extract at 26 mg/kgBW, 52 mg/kgBW, and 104 mg/kgBW, respectively. The average number of spermatogonium cells, spermatocytes, and spermatids increased with the increase in the dose given to the mice. These results indicate that the red bean fermentation extract in all three doses could maintain the number of spermatogonium cells, spermatocytes, and spermatids. Spermatocyte cells and spermatid cells in this study have similar data results, namely, the best dose in the P2 treatment group, which uses a dose of 52 mg/kgBW day, because this group has data results that are not significantly different from group P3, even though the dose in group P2 is lower than that in group P3. The results of this study indicate that group P2, with a dose of 52 mg/kgBW day, plays a good role in maintaining the number of spermatogonium cells, spermatocytes, and spermatids in mice exposed to cigarette smoke. Group P2 with a lower dose showed results that were not significantly different from group P3 with a higher dose. ConclusionBased on the results of the research conducted, it can be concluded that the administration of fermented red bean extract plays a role in reducing damage to spermatogonium cells, spermatocytes, and spermatids in male mice exposed to cigarette smoke. Although there was an increase in the number of spermatogenic cells in the treatment group compared with the positive control group (K+), the number of cells was still significantly different from that in the negative control group (K–). This indicates that cell loss is not completely prevented. Therefore, fermented red bean extract does not completely maintain spermatogenic cell levels under normal conditions but can provide a partial protective effect against cigarette smoke-induced damage. Among the doses tested, a dose of 52 mg/kgBW/day showed the most optimal effectiveness in reducing the decline in the number of spermatogenic cells. AcknowledgmentsThe authors would like to thank the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Universitas Airlangga. Conflict of interest The authors declare no conflict of interest. Funding The author funded this study. Author’s contributions ESN, ARK, TDL, AQD, and TH: conceived the idea and drafted the manuscript. IM, KR, BB, RZA, and SPM: data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation. SDR, GR, BPP, WW, and NC: critically read and revised the manuscript for intellectual content. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript. All authors have read, reviewed, and approved the final version of the manuscript. Data availability All data are available in the revised manuscript. ReferencesAfzal, S., Abdul Manap, A.S., Attiq, A., Albokhadaim, I., Kandeel, M. and Alhojaily, S.M. 2023. From imbalance to impairment: the central role of reactive oxygen species in oxidative stress-induced disorders and therapeutic exploration. Front. Pharmacol. 14(1), 1269581. Alcázar-Valle, M., Lugo-Cervantes, E., Mojica, L., Morales-Hernández, N., Reyes-Ramírez, H., Enríquez-Vara, J.N. and García-Morales, S. 2020. Bioactive compounds, antioxidant Activity, and Antinutritional Content of Legumes: a Comparison between Four Phaseolus Species. Molecules 25(15), 3528. Ammendolia, D.A., Bement, W.M. and Brumell, J.H. 2021. Plasma membrane integrity: implications for health and disease. BMC. Biol. 19(1), 71. An, X., Yu, W., Liu, J., Tang, D., Yang, L. and Chen, X. 2024. Oxidative cell death in cancer: mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities. Cell Death Dis. 15(8), 556. Ayala, A., Muñoz, M.F. and Argüelles, S. 2014. Lipid peroxidation: production, metabolism, and signaling mechanisms of malondialdehyde and 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal. Oxidative Med. Cellular Longevity 1(1), 360438. Barabás, K., Szabó-Meleg, E. and Ábrahám, I.M. 2020. Effect of Inflammation on Female Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH) Neurons: mechanisms and Consequences. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21(2), 529. Castro, M., Leal, K., Pezo, F. and Contreras, M.J. 2025. Sperm membrane: molecular implications and strategies for cryopreservation in productive species. Animals 15(12), 1808. Cha, S.R., Jang, J., Park, S.M., Ryu, S.M., Cho, S.J. and Yang, S.R. 2023. Cigarette smoke-induced respiratory response: insights into cellular processes and biomarkers. Antioxidants 12(6), 1210. Chaudhary, P., Janmeda, P., Docea, A.O., Yeskaliyeva, B., Razis, A.F.A., Modu, B., Calina, D. and Sharifi-Rad, J. 2023. Oxidative stress, free radicals and antioxidants: potential crosstalk in the pathophysiology of human diseases. Front. Chem. 11(1), 1158198. Collison, M.W. 2008. Determination of total soy isoflavones in dietary supplements, supplement ingredients, and soy foods by high-performance liquid chromatography with ultraviolet detection: collaborative study. J. AOAC. Int. 91(3), 489–500. Dai, J.B., Wang, Z.X. and Qiao, Z.D. 2015. The hazardous effects of tobacco smoking on male fertility. Asian J. Androl. 17(6), 954–960. Darbandi, M., Darbandi, S., Agarwal, A., Sengupta, P., Durairajanayagam, D., Henkel, R. and Sadeghi, M.R. 2018. Reactive oxygen species and male reproductive hormones. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 16(1), 87. De Luna, S.L.R., Ramírez-Garza, R.E. and Saldívar, S.O.S. 2020. Environmentally friendly methods for flavonoid extraction from plant material: impact of their operating conditions on yield and antioxidant properties. ScientificWorldJournal 2020(1), 6792069. Delmonte, P. and Rader, J.I. 2006. Analysis of isoflavones in foods and dietary supplements. J. AOAC. Int. 89(4), 1138–1146. Esakky, P. and Moley, K.H. 2016. Paternal smoking and germ cell death: a mechanistic link to the effects of cigarette smoke on spermatogenesis and possible long-term sequelae in offspring. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 435(1), 85–93. Hauger, R.L., Saelzler, U.G., Pagadala, M.S. and Panizzon, M.S. 2022. The role of testosterone, the androgen receptor, and hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis in depression in ageing Men. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 23(6), 1259–1273. Ibtisham, F., Wu, J., Xiao, M., An, L., Banker, Z., Nawab, A., Zhao, Y. and Li, G. 2017. Progress and future prospect of in vitro spermatogenesis. Oncotarget 8(39), 66709–66727. Kasote, D.M., Katyare, S.S., Hegde, M.V. and Bae, H. 2015. Significance of antioxidant potential of plants and its relevance to therapeutic applications. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 11(8), 982–991. Kimura, M., Itoh, N., Takagi, S., Sasao, T., Takahashi, A., Masumori, N. and Tsukamoto, T. 2003. Balance of apoptosis and proliferation of germ cells related to spermatogenesis in aged men. J. Androl. 24(2), 185–191. Kurnijasanti, R. and Candrarisna, M. 2019. The effect of pisang ambon (Musa paradisiaca L.) stem extract on the regulation of IL 1ß, IL 6 and TNF α in rats’ enteritis. Iraqi J. Vet. Sci. 33(2), 407–413. Lobo, V., Patil, A., Phatak, A. and Chandra, N. 2010. Free radicals, antioxidants and functional foods: impact on human health. Pharmacogn. Rev. 4(8), 118–126. Lü, J.M., Lin, P.H., Yao, Q. and Chen, C. 2010. Chemical and molecular mechanisms of antioxidants: experimental approaches and model systems. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 14(4), 840–860. Martemucci, G., Costagliola, C., Mariano, M., D’Andrea, L., Napolitano, P. and D’Alessandro, A.G. 2022. Free radical properties, source and targets, antioxidant consumption and health. Oxygen 2(2), 48–78. Martínez-Alonso, C., Taroncher, M., Castaldo, L., Izzo, L., Rodríguez-Carrasco, Y., Ritieni, A. and Ruiz, M.J. 2022. Effect of phenolic extract from red beans (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) on T-2 toxin-induced cytotoxicity in HepG2 Cells. Foods 11(7), 1033. Novriadi, A., Nooryanto, M., Indrawan, I.W.A. and Handayani, P. 2023. Effect of red bean extract (Phaseolus Vulgaris L. Sp) on interleukin-1, inhibin Β and PCNA expression in systemic lupus erythematosus mice model. Asian J. Heal Res. 2(1), 38–42. Oduwole, O.O., Huhtaniemi, I.T. and Misrahi, M. 2021. The roles of luteinizing hormone, follicle-stimulating hormone and testosterone in spermatogenesis and folliculogenesis revisited. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22(23), 12735. Orak, H.H., Karamac, M. and Amarowicz, R. 2015. Antioxidant activity of phenolic compounds of red bean (Phaseolus vulgarisL.). Oxid. Commun. 38(1), 67–76. Osadchuk, L., Kleshchev, M. and Osadchuk, A. 2023. Effects of cigarette smoking on semen quality, reproductive hormone levels, metabolic profile, zinc and sperm DNA fragmentation in men: results from a population-based study. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 14(1), 1255304. Park, M.G., Ko, K.W., Oh, M.M., Bae, J.H., Kim, J.J. and Moon Du, G. 2012. Effects of smoking on plasma testosterone level and erectile function in rats. J. Sex. Med. 9(2), 472–481. Petersen, R.C. 2017. Free-radicals and advanced chemistries involved in cell membrane organization influence oxygen diffusion and pathology treatment. AIMS. Biophys. 4(2), 240–283. Pham-Huy, L.A., He, H. and Pham-Huy, C. 2008. Free radicals, antioxidants in disease and health. Int. J. Biomed. Sci. 4(2), 89–96. Pizzimenti, S., Ciamporcero, E., Daga, M., Pettazzoni, P., Arcaro, A., Cetrangolo, G., Minelli, R., Dianzani, C., Lepore, A., Gentile, F. and Barrera, G. 2013. Interaction of aldehydes derived from lipid peroxidation and membrane proteins. Front. Physiol. 4(1), 242. Rahma, N., Wurlina, W., Madyawati, S.P., Utomo, B., Hernawati, T. and Safitri, E. 2021. Kaliandra honey improves testosterone levels, diameter and epithelial thickness of seminiferous tubule of white rat (Rattus norvegicus) due to malnutrition through stimulation of HSP70. Open Vet. J. 11(3), 401–406. Roy, A., Khan, A., Ahmad, I., Alghamdi, S., Rajab, B.S., Babalghith, A.O., Alshahrani, M.Y., Islam, S. and Islam, M.R. 2022. Flavonoids a bioactive compound from medicinal plants and its therapeutic applications. Biomed. Res. Int. 1(1), 5445291. Sengupta, P., Pinggera, G.M., Calogero, A.E. and Agarwal, A. 2024. Oxidative stress affects sperm health and fertility-Time to apply facts learned at the bench to help the patient: lessons for busy clinicians. Reprod. Med. Biol. 23(1), e12598. Seo, Y.S., Park, J.M., Kim, J.H. and Lee, M.Y. 2023. Cigarette Smoke-Induced Reactive Oxygen Species Formation: a Concise Review. Antioxidants (Basel). 12, 1732. Sharifi-Rad, M., Kumar, N.V.A., Zucca, P., Varoni, E.M., Dini, L., Panzarini, E., Rajkovic, J., Fokou, P.V.T., Azzini, E., Peluso, I., Mishra, A.P., Nigam, M., El Rayess, Y., Beyrouthy, M.E., Polito, L., Iriti, M., Martins, N., Martorell, M., Docea, A.O., Setzer, W.N., Calina, D., Cho, W.C. and Sharifi-Rad, J. 2020. Lifestyle, oxidative stress, and antioxidants: back and forth in the pathophysiology of chronic diseases. Front. Physiol. 11(1), 694. Siddiqui, S.A., Erol, Z., Rugji, J., Taşçı, F., Kahraman, H.A., Toppi, V., Musa, L., Di Giacinto, G., Bahmid, N.A., Mehdizadeh, M. and Castro-Muñoz, R. 2023. An overview of fermentation in the food industry - looking back from a new perspective. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 10(1), 85. Slaoui, M. and Fiette, L. 2011. Histopathology procedures: from tissue sampling to histopathological evaluation. Methods Mol. Biol. 691(1), 69–82. Treml, J. and Šmejkal, K. 2016. Flavonoids as potent scavengers of hydroxyl radicals. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 15(4), 720–738. Wang, Y., Fu, X. and Li, H. 2025. Mechanisms of oxidative stress-induced sperm dysfunction. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 16(1), 1520835. | ||

| How to Cite this Article |

| Pubmed Style Novanto ES, Khairullah AR, Budiarto B, Lestari TD, Madyawati SP, Hernawati T, Rachmawati K, Mustofa I, Rasad SD, Dawood AQ, Riady G, Wasito W, Ahmad RZ, Pratama BP, Chairuman N. Effect of fermented red bean extract (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) on spermatogenic cells in mice exposed to smoke. Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(9): 4146-4152. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i9.20 Web Style Novanto ES, Khairullah AR, Budiarto B, Lestari TD, Madyawati SP, Hernawati T, Rachmawati K, Mustofa I, Rasad SD, Dawood AQ, Riady G, Wasito W, Ahmad RZ, Pratama BP, Chairuman N. Effect of fermented red bean extract (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) on spermatogenic cells in mice exposed to smoke. https://www.openveterinaryjournal.com/?mno=266264 [Access: January 25, 2026]. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i9.20 AMA (American Medical Association) Style Novanto ES, Khairullah AR, Budiarto B, Lestari TD, Madyawati SP, Hernawati T, Rachmawati K, Mustofa I, Rasad SD, Dawood AQ, Riady G, Wasito W, Ahmad RZ, Pratama BP, Chairuman N. Effect of fermented red bean extract (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) on spermatogenic cells in mice exposed to smoke. Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(9): 4146-4152. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i9.20 Vancouver/ICMJE Style Novanto ES, Khairullah AR, Budiarto B, Lestari TD, Madyawati SP, Hernawati T, Rachmawati K, Mustofa I, Rasad SD, Dawood AQ, Riady G, Wasito W, Ahmad RZ, Pratama BP, Chairuman N. Effect of fermented red bean extract (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) on spermatogenic cells in mice exposed to smoke. Open Vet. J.. (2025), [cited January 25, 2026]; 15(9): 4146-4152. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i9.20 Harvard Style Novanto, E. S., Khairullah, . A. R., Budiarto, . B., Lestari, . T. D., Madyawati, . S. P., Hernawati, . T., Rachmawati, . K., Mustofa, . I., Rasad, . S. D., Dawood, . A. Q., Riady, . G., Wasito, . W., Ahmad, . R. Z., Pratama, . B. P. & Chairuman, . N. (2025) Effect of fermented red bean extract (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) on spermatogenic cells in mice exposed to smoke. Open Vet. J., 15 (9), 4146-4152. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i9.20 Turabian Style Novanto, Elias Setyo, Aswin Rafif Khairullah, Budiarto Budiarto, Tita Damayanti Lestari, Sri Pantja Madyawati, Tatik Hernawati, Kadek Rachmawati, Imam Mustofa, Siti Darodjah Rasad, Ahmed Qasim Dawood, Ginta Riady, Wasito Wasito, Riza Zainuddin Ahmad, Bima Putra Pratama, and Novia Chairuman. 2025. Effect of fermented red bean extract (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) on spermatogenic cells in mice exposed to smoke. Open Veterinary Journal, 15 (9), 4146-4152. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i9.20 Chicago Style Novanto, Elias Setyo, Aswin Rafif Khairullah, Budiarto Budiarto, Tita Damayanti Lestari, Sri Pantja Madyawati, Tatik Hernawati, Kadek Rachmawati, Imam Mustofa, Siti Darodjah Rasad, Ahmed Qasim Dawood, Ginta Riady, Wasito Wasito, Riza Zainuddin Ahmad, Bima Putra Pratama, and Novia Chairuman. "Effect of fermented red bean extract (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) on spermatogenic cells in mice exposed to smoke." Open Veterinary Journal 15 (2025), 4146-4152. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i9.20 MLA (The Modern Language Association) Style Novanto, Elias Setyo, Aswin Rafif Khairullah, Budiarto Budiarto, Tita Damayanti Lestari, Sri Pantja Madyawati, Tatik Hernawati, Kadek Rachmawati, Imam Mustofa, Siti Darodjah Rasad, Ahmed Qasim Dawood, Ginta Riady, Wasito Wasito, Riza Zainuddin Ahmad, Bima Putra Pratama, and Novia Chairuman. "Effect of fermented red bean extract (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) on spermatogenic cells in mice exposed to smoke." Open Veterinary Journal 15.9 (2025), 4146-4152. Print. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i9.20 APA (American Psychological Association) Style Novanto, E. S., Khairullah, . A. R., Budiarto, . B., Lestari, . T. D., Madyawati, . S. P., Hernawati, . T., Rachmawati, . K., Mustofa, . I., Rasad, . S. D., Dawood, . A. Q., Riady, . G., Wasito, . W., Ahmad, . R. Z., Pratama, . B. P. & Chairuman, . N. (2025) Effect of fermented red bean extract (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) on spermatogenic cells in mice exposed to smoke. Open Veterinary Journal, 15 (9), 4146-4152. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i9.20 |