| Research Article | ||

Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(5): 2059-2065 Open Veterinary Journal, (2025), Vol. 15(5): 2059-2065 Research Article Behavior of female Tarsius spectrumgurskyae at the primate research center breeding facilityNanik Hidayatik1*, Muhammad Agil2, Entang Iskandar3, Dyah Perwitasari-Farajallah3,4, Aswin Rafif Khairullah5, Suryo Saputro3, and Valen Sakti Maulana31Division of Basic Veterinary Medicine, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Universitas Airlangga, Surabaya, Indonesia 2Division of Veterinary Clinic Reproduction and Pathology, School of Veterinary Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, IPB University, Bogor, Indonesia 3Primate Research Center, IPB University, Bogor, Indonesia 4Department of Biology, Faculty of Sciences, IPB University, Bogor, Indonesia 5Research Center for Veterinary Science, National Research and Innovation Agency (BRIN), Bogor, Indonesia *Corresponding Author: Nanik Hidayatik. Division of Basic Veterinary Medicine, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Universitas Airlangga, Surabaya, Indonesia. Email: nanik.h [at] fkh.unair.ac.id Submitted: 21/1/2025 Revised: 14/04/2025 Accepted: 25/4/2025 Published: 31/05/2025 © 2025 Open Veterinary Journal

ABSTRACTBackground: Behavioral studies are crucial for ex situ conservation because animals must exhibit natural behavior as a principle of animal welfare. To achieve this, the behaviors of animals in captivity must be compared with those of animals residing in their natural habitats to ensure that they live naturally. Aim: This study aimed to describe the behaviors of female Tarsius spectrumgurskyae in captivity to facilitate comparisons with wild individuals. Methods: The subjects of this study were three adult T. spectrumgurskyae females observed for 15 months in a captive breeding facility at the Primate Research Center of IPB University, Bogor. Results: Female T. spectrumgurskyae spend most of their time moving (45.55%) or resting (36.52%). The grooming behaviors of female tarsiers (6.52%), including autogrooming and allogrooming, were also recorded. T. spectrumgurskyae reported urination (4.11%), which exhibits sexual behavior (3.58%), eat (2.25%), vocalize (0.90%), drinking (0.30%), and defecate (0.24%). T. spectrumgurskyae consumed more crickets (73.26%) than Hong Kong caterpillars (19.02%). Because the captive breeding facility was a semiopen cage, they could still prey on wild insects, such as flying white ants, moths, lizards, and spiders, coming to their cages (7.72%). Conclusion: Based on these results, we confirmed that T. spectrumgurskyae can express its natural behavior in a captive breeding environment. However, some activity budgets, including locomotion and resting, were greater in this study than in the natural habitats due to food source availability. Modifications to the animals’ environments or changes in feeding methods may increase activity and behavioral diversity to more closely emulate wild populations. Keywords: Activity budget, behavior, captive, conservation, Tarsius spectrumgurskyae. IntroductionSulawesi is a highly diverse island in Indonesia, particularly in terms of the presence of primates (Supriatna et al., 2015; Wulandari et al., 2022; Pramana et al., 2022). There are 17 endemic primate species in Sulawesi, belonging to only two genera: Tarsius and Macaca. However, they have experienced the threat of forest loss in the last decade. On the island of Sulawesi, forests have been converted to agricultural land comprising oil palm, maize, and cocoa. Their forested environments have shrunk dramatically from approximately 45% to 15% (Supriatna et al., 2015; Supriatna et al., 2020). The distribution of the spectral tarsier is not limited to the inside of the forest area but also to the outside of the forest area (Saroyo et al., 2017). Thus, conservation programs for Tarsius and Macaca from Sulawesi need to be planned appropriately based on the natural biology of the species. Tarsiers have unique anatomical and physiological features and genetic structures that make them very special, known as small body primate (weight 110–140g) with big eyes as an adaptation to their nocturnal living, long legs as adaptations for vertical clinging and leaping mode of locomotion, obligate carnivorous (predominantly insectivorous) (MacKinnon and MacKinnon, 1980; Roberts and Cunningham, 1986; Gursky, 2000b). The Tarsier phylogenetic position represents an important link between the strepsirhines and haplorhines, and their intra-island diversification was spurred by land emergence and a rapid succession of glacial cycles during the Plio-Pleistocene (Driller et al., 2009; Driller et al., 2015; Heerschop et al., 2016; Sumampow et al., 2019). There are three genera of tarsiers: Tarsius, Cephalopacus, and Carlito (Groves and Shekelle, 2010). The Tarsius genus contained the most species among the other tarsier genera, with 11 species. Tarsius spectrumgurskyae is a new species in the genus, Tarsius. This species was initially known as a spectral tarsier (T. spectrum/T. tarsier) and studied by Dr Sharon Gursky (Shekelle et al., 2017). Genetic analysis identified the T. spectrum in the breeding facility of the Primate Research Center (PRC), IPB University, as T. spectrumgurskyae (Saepuloh et al., 2019). Tarsius spectrumgurskyae is included in the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species and is considered vulnerable (Shekelle, 2020). Therefore, breeding programs for these species are required. Studies of the three genera of tarsiers existing in the wild were reported more exclusively than those in captivity. Specific knowledge of an animal’s behavioral repertoire in its natural environment is required for understanding their natural behavior (Sueur and Pelé, 2019). Several eastern tarsier field studies have investigated the behavior, ecology, population, and taxonomy of these species. Tarsius’ behavior in their natural habitat, including specific behaviors, such as social behavior, infant care, allo-care, dispersal patterns, avoiding predators, gregarious behavior, behavior during seasonality, and vocalization, has been more extensively studied (MacKinnon and MacKinnon, 1980; Gursky, 1994; Gursky, 2000a; Gursky, 2000c; Gursky, 2002a; Gursky, 2015; Gursky, 2019). To support the ex situ conservation of Tarsius, many captive studies have investigated its diet, enclosure and enrichment, locomotor position, sexual behavior, reproductive status, and longevity (Dahang et al., 2008; Severn et al., 2008; Shekelle and Nietsch, 2008; Dahang, 2016 Hidayatik et al., 2018a, b). However, few studies have investigated Tarsius’ time budget for behavior in captivity. Breeding tarsiers in captivity is challenging because they are susceptible to stress and their offspring are less likely to survive (Haring and Wright, 1989; Wright et al., 2003; Severn et al., 2008; Wojciechowski et al., 2019). Few studies have investigated the behavior of T. spectrumgurskyae in captivity. Therefore, a study of the behavior of T. spectrumgurskyae in captivity is needed based on their daily behavioral aspects. This study aimed to identify the behavior of T. spectrumgurskyae in captivity and to provide preliminary information on this behavior. Materials and MethodsResearch site and subjectThis study was part of the tarsier behavior and reproductive hormone collaboration project conducted by the PRC, IPB University, and the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine of Universitas Airlangga. Behavioral observations were conducted at the breeding facility of the PRC, IPB University. Two females were observed for 15 months (January 2015 to March 2016), and one female was observed for six months (January 2015–June 2015) because of death while giving birth (dystocia). The subjects were habituated before this study to prevent animal stress. Three adult female T. spectrumgurskyae were housed in family groups. Group one was a pair of adult male and female T. spectrumgurskyae. The second group included adult males and females and two offspring. The last group consisted of an adult male and an adult female with young children. Each family group was housed in a connected double cage measuring 1.5 × 1.2 × 2.4 m and equipped with environmental enrichments, such as feeding boxes, drinking containers, nest boxes, pipes, bamboo, branches, and a net 0.6 m above the floor. The enclosure was semiopen to allow Tarsier to recognize day and night. Two small lamps were installed in the middle of the enclosure and at one of the edges to continuously illuminate the enclosure during the day and night and to acclimate the animals to night observation conditions. Crickets and Hong Kong caterpillars were provided as food, and drinking water was available ad libitum. The daily temperature and humidity were between 20–28°C and 35–74%, respectively. Behavior observation procedureThe behavior of female T. spectrumgurskyae was observed in their group using the method of focal animal sampling, three times a week at 5–9 p.m. for 20 minutes at 5-minute intervals; all of their behaviors were recorded (Altmann, 1974). The behavioral categories are listed in Table 1. The four-hour observation session procedure was adapted from that of Hidayatik et al. (2018b). Data analysisThe activities of female T. spectrumgurskyae were quantitatively described by computing the percentage of each occurring behavior relative to the total occurring behavior as follows:

Description: P=percentage of activity A=average of all activities during the observation period B=the average total of all activities during observation. The behavioral data of the study population and selected behavioral data (resting, traveling, foraging, allogrooming, vocalizing, scent marking, and copulating) of all night follow of wild population references (Gursky, 2000c; Gursky, 2005a) were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 27 (IBM Corp. 2020). The independent sampled t-test was used to compare captive and wild population behaviors. The food consumption data of Tarsius were analyzed using analysis of variance (ANOVA). If a significant difference was found, Duncan’s multiple range test was conducted at a significance level of 0.05. Table 1. The ethogram of behavioral categories of female T. spectrumgurskyae in captive breeding at the PRC-IPB University.

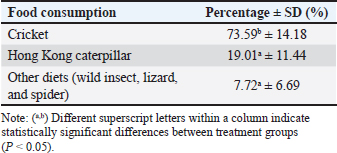

Ethical approvalThis study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the PRC, IPB University (document number ACUC No. IPB PRC-15-C0010). ResultsThe total observation duration of this study was 433.7 hours. In the total period of observation, the female T. spectrumgurskyae spent most of their time moving (45.55%) or resting (36.52%). Grooming (6.52%) includes autogrooming and allogrooming. They reported urination (4.11%), sexual behavior (3.58%), feeding (2.25%), vocalization (0.90%), drinking (0.30%), and defecation (0.24%). The results are presented in Table 2. There were no statistically significant differences in captive T. Spectrumgurskyae behavior in wild populations following Gursky (2000c) and Gursky (2005a) in sexual activity. However, feeding, urination, resting, locomotion, grooming, and vocalizing were significantly different between the wild population (2000c) and Gursky (2005a) (Table 3). The tarsiers were supplied with two types of food: crickets and Hong Kong caterpillars. They consumed significantly more crickets (73.59% ± 14.18%) than Hong Kong caterpillars (19.01 ± 11.44%) in this study. The captive breeding facility was a semiopen cage; thus, the tarsier could prey on various wild insects, such as flying white ants, moths, lizards, and spiders (7.72 ± 6.69%) (Table 4). However, because of the difficulty in identification, insect prey classification was not performed. Table 2. Time budget of female T. spectrumgurskyae in the captive breeding facility of the PRC-IPB.

DiscussionThese results confirm that T. spectrumgurskyae can express its natural behavior in a captive breeding environment, although this study has limitations due to the period of observation only for around 5–9 p.m of the night activity. However, some activity budgets for all nights follow in the field, including locomotion and rest, were greater in this study than in the field. Wild spectral tarsiers spend 55% of their time foraging, 16% resting, and 6% socializing (Gursky, 2005a). For traveling, 23% (Gursky, 2005a) and 63% (Gursky, 2000c), and 7% spent scent marking/urinating (Gursky, 2000c), whereas during this study, the captive tarsiers spent 45.55% time moving, 36.52% resting, 6.52% grooming, 4.11% urinating, 3.58% sexual behavior, 2.25% feeding, 0.90% vocalization, drinking (0.30%), and 0.24% defecation time. The differences between wild and captivity environments might play a role in increasing and decreasing behavior. Primate activity is influenced by environmental conditions, sex, age, and social patterns (Gursky, 2000c; Hosey, 2005; Wojciechowski et al., 2019). Table 3. The behavior frequency analysis between the captive tarsier of this study and the wild population reported from references using the t-test.

This captive breeding used in study is a semiopen cage, which is the ideal habitat for tarsiers to reproduce in captivity. Tarsiers were naturally surrounded by natural flora and were allowed to experience the local environment with all fluctuations (temperature, humidity, rain, and so on) (Ŕeháková, 2018). The temperature of the T. spectrumgurskyae natural habitat (Batuputih NTP, Bitung City, North Sulawesi, Indonesia) of the sleeping tree was 24°C–27°C with a humidity of 81%–99%. The daily range of temperatures and humidity in this study were between 20°–28°C and 35%–74%. The pattern of wildlife spatial distribution is significantly influenced by environmental temperature. Thus, humidity and temperature are considered limiting factors for the survival of wildlife (Rosyid et al., 2019). The results showed that in this captive breeding environment, T. spectrumgurskyae could well survive. Locomotor activity in the captivity group was greater than that in the wild tarsier group. This increase is affected by social interaction between female and male students. Captive female T. spectrumgurskyae increased their locomotion postcopulation to avoid males (Hidayatik et al., 2018b), and when a wild food source was coming to the cage, such as flying white ants. Moreover, observations have revealed that the traveling and foraging activities of wild T. spectrumgurskyae are influenced by seasonal changes (Gursky, 2000a). All females moved around by leaping, clinging, climbing, and walking in the first hour of activity. In addition, the study is limited to female behavior during the several hours after starting the activity. In this observation period, the peak locomotor activity of wild tarsiers occurs in the early stages of dusk and just before they go to sleep in the morning (Merker, 2006). This result is attributed to the study results being higher than those in the wild population. Thus, a peak was also observed for captive T. syrichta (Wojciechowski et al., 2019). Female T. spectrumgurskyae move around while carrying their infant in their mouths. During feeding, the infant is transported to a nearby substrate. Therefore, more activities are performed by wild female tarsiers (Gursky, 1994; MacKinnon and MacKinnon, 1980; Gursky, 2002c). Table 4. The proportion of food consumed by female T. spectrumgurskyae in the captive breeding facility of the PRC-IPB was analyzed using ANOVA and Duncan’s multiple range test

The present study shows that captive female T. spectrumgurskyae spend more time resting than wild tarsiers, representing half of the wild tarsiers resting (Gursky, 2005b). Increased resting time suggests that food sources’ availability reduces foraging time (Gursky, 2000a). The cage size for the nonhuman primates in this study was in accordance with the National Research Council (US) Committee for the Update of the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (2011); however, it might have been a limited space compared with the wild, affected by increasing resting space. On the other hand, in the wild, T. spectrumgurskyaes live in groups of 2–8 individuals per group (Arrijani and Rizki, 2020). Both wild and captive female T. spectrumgurskyae are more gregarious than their sister species and have been observed to rest with males and their offspring (Gursky, 1994; Gursky, 2000a; Gursky, 2000b). In contrast to the wild family tarsier, female T. spectrumgurskyae preferred to sleep with all family members in the nest box or on horizontal branches rather than in the nest box. Another study reported this finding for captured T. syrichta (Reason, 1978). Grooming in captive Tarsiers was significantly lower than that in the wild population. T. spectrumgusrkyae females were autogroomed and allogroomed with males and offspring. Moreover, spectral tarsiers spend 14% of their time allogrooming in their natural habitat with various numbers of group members (2–6 individuals) consisting of adult males, adult females, and their offspring (Gursky, 2000c). Mothers have been reported to be in physical contact with their infants more often during grooming (Gursky, 1994; Ŕeháková, 2018). In their natural habitat, subadult females groom infants in their group (Gursky, 2000a). This finding is in contrast with those of captive T. bancanus and T. syrichta, which never underwent allogrooming (Roberts and Cunningham, 1986; Wojciechowski et al., 2019). However, the percentage of grooming performed in this study was similar to that of captive T. bancanus (Roberts and Kohn, 1993). However, this was greater in paired females of T. syrichta (Wojciechowski et al., 2019). In this study, the percentage of feeding activity was not suitable for comparison with that of the wild population because of the references for foraging. However, the percentage of feeding activity by T. spectrumgurskyae was similar to that of T. bancanus. The wild eastern tarsier is an obligate faunivore that feeds primarily on insects and other prey, such as snakes, birds, and bats (MacKinnon and MacKinnon, 1980; Gursky, 2000a; Dahang et al., 2008). Live crickets are reported to be their favorite food in captivity (Roberts and Cunningham, 1986; Roberts and Kohn, 1993). This study revealed that some wild insects are likely to be affected by light exposure. For example, flying white ants sometimes fly by circling the cage lamp; thus, they initiate the hunting activity of tarsiers. In tarsier genera, drinking activity has also been reported, as the animal licked water directly from the drinking container (Roberts and Kohn, 1993). The behaviors with the lowest percentages were urination, defecation, sexual behavior, and vocalization. Sexual behaviors were not significantly different, but urination and vocalizing behaviors differed significantly from those of the wild population. During the observation period, the females persistently urinated but usually defecated once or twice. They preferred defecation on the vertical branch, primarily at the same site. Urinating tarsiers are markers of territorial and sexual arousal (MacKinnon and MacKinnon, 1980; Wright et al., 1986; Gursky-Doyen, 2010; Hidayatik et al., 2018b). The results of this study showed that the sexual behavior of tarsiers in the wild and captive breeding did not differ significantly. This condition could occur because the female tarsier reported only accepted the male on the first day of estrous period, both in the wild and captive (Wright et al., 1986; Gursky, 1994; Hidayatik et al., 2018b). The lower percentage of vocalizations in this study may be due to the study being conducted only in the evening, while T. specturmgurskyae do duet calls vocalize in the morning too. Spectral tarsiers in the wild have been reported to be more social, including vocalizing, than Western and Philippine tarsiers. Female tarsiers always produce duet calls with males at the start and end of their activities (MacKinnon and MacKinnon, 1980; Gursky, 2000c). In contrast, T. bancanus and T. syrichta do not produce duet calls (Roberts and Kohn, 1993; Wharton, 1947; Wojciechowski, et al., 2019; Yustian et al., 2021). Male T. bancanus emit courtship calls before mating (Wright et al., 1986). T. spectrumgurskyae also emit alarm calls when they see cats and civets or hear thunder. Alarm calls have also been reported for T. spectrumgurskyae and Cephalopachus bancanus in wild populations (Gursky, 2002c; Gursky, 2003; Gursky, 2005b; Yustian et al., 2021). ConclusionThe natural behavior of T. spectrumgurskaye in captivity was examined. Although the small sample size limits the results of this study, they provide insight into T. spectrumgurskyae behavior in captivity and several considerations for the breeding management of T. Spectrumgurskyae in captivity, such as spreading food among cage substrates to trigger foraging behavior. Further studies on the behavior of T. spectrumgurskyae in the broader observation window to obtain a more complete behavioral profile, studies on long-term behavioral adaptations or physiological stress markers, studies on behavior with potential hormonal or social influences, and behavioral focus on sex and age differences in the future would support our findings. AcknowledgmentOur sincere gratitude goes to the Dean of the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine and the Director of the PRC, IPB University (PSSP-IPB), for their support of this research. Moreover, we thank Luviana Kristianingtyas and Puput Ade Wahyuningtyas for their assistance in compiling the behavioral data. The collection of observational data adhered to animal welfare concern requirements and fulfilled the legal requirements of the host country, Indonesia. The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest. FundingThis research was supported by Hibah Riset Mandat Dosen Muda, Universitas Airlangga (grant number: 397/UN3.14/PT/2020. Author’s contributionsConceived, designed, and coordinated the study: NH and SS. Designed data collection tools, supervised the field sample and data collection, laboratory work, and data entry: MA. Validation, supervision, and formal analysis: VSM. Contributed reagents, materials, and analysis tools: EI and DP-F. Statistical analysis and interpretation and participated in the preparation of the manuscript: ARK. All authors have read, reviewed, and approved the final manuscript. Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest. Data availabilityAll data supporting the findings of this study are available in the manuscript, and no additional data sources are required. ReferencesAltmann, J. 1974. Observational study of behavior: sampling methods. Behaviour 49(3), 227–2267. Arrijani and Rizki, M. 2020. Vegetation analysis and population of tarsier (Tarsius spectrumgurskyae) at Batuputih Nature Tourism Park, North Sulawesi, Indonesia. Biodiversitas 20(2), 530–537. Dahang, D. 2016. Posisi pergerakan Tarsius tarsier erxleben 1777 dan Tarsius bancanus horsfield 1821 di penangkaran. J. Saintech. 8(4), 33–42. Dahang, D., Severn, K. and Shekelle, M. 2008. Eastern tarsiers in captivity, part II: a preliminary assessment of diet. In: Primates of the oriental night. Eds., Shekelle, M., Groves, C., Maryanto, I., Schulze, H. and Fitch-Snyder, H. Kozhikode: LIPI Press, pp: 97–103. Driller, C., Merker, S., Perwitasari-Farajallah, D., Sinaga, W., Anggraeni, N. and Zischler, H. 2015. Stop and go – waves of tarsier dispersal mirror the genesis of Sulawesi Island. PLoS One 10(11), e0141212 Driller, C., Perwitasari-Farajallah, D., Zischler, H. and Merker, S. 2009. The social system of lariang tarsiers (Tarsius lariang) as revealed by genetic analyses. Int. J. Primatol. 30(2), 267–281. Groves, C. and Shekelle, M. 2010. The genera and species of Tarsiidae. Int. J. Primatol. 31(6), 1071–1082. Gursky, S. 2000a. Allocare in a nocturnal primate: data on the spectral tarsier, Tarsius spectrum. Folia Primatol. (Basel) 71(1–2), 39–54. Gursky, S. 2000b. Effect of seasonality on the behavior of an insectivorous primate, Tarsius spectrum. Int. J. Primatol. 21(3), 477–495. Gursky, S. 2000c. Sociality in the spectral tarsier, Tarsius spectrum. Am. J. Primatol. 51(1), 89–101. Gursky, S. 2002a. Determinants of gregariousness in the spectral tarsier (Prosimian: Tarsius spectrum). J. Zool. 256(3), 401–410. Gursky, S. 2002b. Predation on a wild spectral tarsier (Tarsius spectrum) by a snake. Folia Primatol. 73(1), 60–62. Gursky, S. 2002c. The behavioral ecology of the spectral tarsier, Tarsius spectrum. Evol. Anthropol. 11(6), 226–234. Gursky, S. 2003. Predation experiments on infant spectral tarsiers (Tarsius spectrum). Folia Primatol. 74(5–6), 272–284. Gursky, S. 2005a. Associations between adult spectral tarsiers. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 128(1), 74–83. Gursky, S. 2005b. Predator mobbing in Tarsius spectrum. Int. J. Primatol. 26(1), 207–221. Gursky, S. 2015. Ultrasonic vocalizations by the spectral tarsier, Tarsius spectrum. Folia Primatol. 86(3), 153–163. Gursky, S. 2019. Echolocation in a nocturnal primate?. Folia Primatol. 90(5), 379–391. Gursky, S.L. 1994. Infant care in the spectral tasier (Tarsis spectrum) Sulawesi, Indonesia. Int. J. Primatol. 15(1), 843–853. Gursky-Doyen, S. 2010. Intraspecific variation in the mating system of spectral tarsiers. Int. J. Primatol. 31(6), 1161–1173. Haring, D.M. and Wright, P.C. 1989. Hand-raising a Philippine tarsier, Tarsius syrichta. Zoo Biol. 8(3), 265–274. Heerschop, S., Zischler, H., Merker, S., Perwitasari-Farajallah, D. and Driller, C. 2016. The pioneering role of PRDM9 indel mutations in tarsier evolution. Sci. Rep. 6(1), 34618. Hidayatik, N., Agil, M., Heistermann, M., Iskandar, E., Yusuf, T.L. and Sajuthi, D. 2018a. Assessing female reproductive status of spectral tarsier (Tarsius tarsier) using fecal steroid hormone metabolite analysis. Am. J. Primatol. 80(11), e22917. Hidayatik, N., Yusuf, T.L., Agil, M., Iskandar, E. and Sajuthi, D. 2018b. Sexual behavior of the spectral tarsier (Tarsius spectrum) in captivity. Folia Primatol. 89(2), 157–164. MacKinnon, J. and MacKinnon, K. 1980. The behavior of wild spectral tarsiers. Int. J. Primatol. 1(1), 361–379. Merker, S. 2006. Habitat-specific ranging patterns of Dian’s tarsiers (Tarsius dianae) as revealed by radiotracking. Am. J. Primatol. 68(2), 111-25. National Research Council (US) Committee for the Update of the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. 2011. Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals. 8th edition. Washington (DC): National Academies Press. Pramana, G.T.S., Prasetyo, L.B. and Iskandar, E. 2022. The habitat suitability modelling of dare monkey (Macaca maura) in Bantimurung Bulusaraung National Park, South Sulawesi. J. Nat. Resour. Environ. Manag. 13(1), 57–67. Reason, R.G. 1978. Support use behavior mindanao tarsier (Tarsius syrichta carbonarius). J. Mammal. 59(1), 205–206. Ŕeháková, M. 2018. Preliminary observations of infant ontogeny in the Philippine tarsier (Tarsius syrichta) and the first description of play behavior and its ontogeny in tarsiers. In Primates. Ed., Burke, M. London: InTech Open Access Publisher. Roberts, M. and Cunningham, B. 1986. Space and substrate use in captive western tarsiers, Tarsius bancanus. Int. J. Primatol. 7(1), 113–130. Roberts, M. and Kohn, F. 1993. Habitat use, foraging behavior, and activity patterns in reproducing western tarsiers, Tarsius bancanus, in captivity: a management synthesis. Zoo Biol. 12(2), 217–232. Rosyid, A., Santosa, Y., Jaya, I.N.S., Bismark, M., Kartono, A.P. 2019. Spatial distribution pattern of Tarsius Lariang in lore lindu national park. Indonesian J. Electric. Eng. Comput. Sci. 13(2): 606-614. Saepuloh, U., Savira, H. and Perwitasari-Farajallah, D. 2019. Non-invasive identification of tarsier species using Cyt b and D-Loop region of mitochondrial DNA as molecular marker. indonesian primate congress, Yogyakarta, 18–20 September 2019. Saroyo, Tallei, T.E., Koneri, R. 2017. Density of spectral tarsier (Tarsius spectrum) in agricultural land, m angrove, and bush habitats in North Sulawesi, Indonesia. Biosci. Res. 14(2), 310–314. Severn, K., Dahang, D. and Shekelle, M. 2008. Eastern tarsiers in captivity, Part I: enclosure and enrichment. In: Primates of the oriental night. Chapter: 8, Eds., Shekelle, M., Groves, C., Maryanto, I., Schulze, H. and Fitch-Snyder, H. Kozhikode: LIPI Press, pp: 91–96. Shekelle, M. 2020. Tarsius spectrumgurskyae. The IUCN red list of threatened species 2020. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN. Shekelle, M. and Nietsch, A. 2008. Tarsier longevity: data from a recapture in the wild and from captive animals. In: Primates of the Oriental Night. Chapter: 7. Eds., Shekelle, M., Groves, C., Maryanto, I., Schulze, H. and Fitch-Snyder, H.Kozhikode: LIPI Press, pp: 85–89. Shekelle, M., Groves, C.P., Maryanto, I. and Mittermeier, R.A. 2017. Two new tarsier species (Tarsiidae, Primates) and the biogeography of Sulawesi, Indonesia. Primate Conserv. 31(1), 61–70. Sueur, C. and Pelé, M. 2019. Importance of living environment for the welfare of captive animals: behaviors and enrichment. In: Animal welfare: from science to law. Eds., Hild S. and Schweitzer, L. Chapter: XVIII. Paris, France: L’Harmattan, pp: 175–188. Sumampow, T.C.P., Shekelle, M., Beier, P., Walker, F.M. and Hepp, C.M. 2020. Identifying genetic relationships among tarsier populations in the islands of Bunaken National Park and mainland Sulawesi. PLoS One 15(3), e0230014. Supriatna, J., Shekelle, M., Fuad, H.A.H., Winarni, N.L., Dwiyahreni, A.A., Farid, M., Mariati, S., Margules, C., Prakoso, B. and Zakaria, Z. 2020. Deforestation on the Indonesian island of Sulawesi and the loss of primate habitat. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 24(1), e01205. Supriatna, J., Winarni, W.L. and Dwiyahreni, A.A. 2015. Primates of Sulawesi: An Update on Habitat Distribution, Population and Conservation. Tabronica 7(3), 170–192. Wharton, C.H. 1947. The Tarsier in Captivity. J. Mammal. 31(3), 260–268. Wojciechowski, F.J., Kaszycka, K.A., Wielbass, A.M. and Řeháková, M. 2019. Activity Patterns of Captive Philippine Tarsiers (Tarsius syrichta): Differences Related to Sex and Social Context. Folia Primatol. 90(2), 109–123. Wright, P.C, Simons E.L. and Gursky, S. 2003. Tarsiers: Past, Present, and Future. Rutgers, NJ: Rutgers University Press. Wright, P.C., Toyama, L.M. and Simons, E.L. 1986. Courtship and copulation in Tarsius bancanus. Folia Primatol. 46(3), 142–148. Wulandari, S.A.M., Perwitasari-Farajallah, D. and Sulistiawati, E. 2022. the gastrointestinal parasites in habituated group of sulawesi black-crested macaque (Macaca nigra) in Tangkoko, North Sulawesi. J. Trop. Biodivers. Biotechnol. 7(3), jtbb73044. Yustian, I., Kurniawan, D., Effendi, Z., Setiawan, D., Patriono, E., Hanum, L. and Setiawan, A. 2021. Vocalization of Western Tarsier ( Cephalopachus bancanus Horsfield, 1821) in Bangka Island, Indonesia. J. Trop. Biodivers. Biotechnol. 6(3), jtbb65526. | ||

| How to Cite this Article |

| Pubmed Style Hidayatik N, Agil M, Iskandar E, Perwitasari-farajallah D, Khairullah AR, Saputro S, Maulana VS. Behavior of female Tarsius spectrumgurskyae at the primate research center breeding facility. Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(5): 2059-2065. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i5.22 Web Style Hidayatik N, Agil M, Iskandar E, Perwitasari-farajallah D, Khairullah AR, Saputro S, Maulana VS. Behavior of female Tarsius spectrumgurskyae at the primate research center breeding facility. https://www.openveterinaryjournal.com/?mno=238983 [Access: January 11, 2026]. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i5.22 AMA (American Medical Association) Style Hidayatik N, Agil M, Iskandar E, Perwitasari-farajallah D, Khairullah AR, Saputro S, Maulana VS. Behavior of female Tarsius spectrumgurskyae at the primate research center breeding facility. Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(5): 2059-2065. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i5.22 Vancouver/ICMJE Style Hidayatik N, Agil M, Iskandar E, Perwitasari-farajallah D, Khairullah AR, Saputro S, Maulana VS. Behavior of female Tarsius spectrumgurskyae at the primate research center breeding facility. Open Vet. J.. (2025), [cited January 11, 2026]; 15(5): 2059-2065. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i5.22 Harvard Style Hidayatik, N., Agil, . M., Iskandar, . E., Perwitasari-farajallah, . D., Khairullah, . A. R., Saputro, . S. & Maulana, . V. S. (2025) Behavior of female Tarsius spectrumgurskyae at the primate research center breeding facility. Open Vet. J., 15 (5), 2059-2065. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i5.22 Turabian Style Hidayatik, Nanik, Muhammad Agil, Entang Iskandar, Dyah Perwitasari-farajallah, Aswin Rafif Khairullah, Suryo Saputro, and Valen Sakti Maulana. 2025. Behavior of female Tarsius spectrumgurskyae at the primate research center breeding facility. Open Veterinary Journal, 15 (5), 2059-2065. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i5.22 Chicago Style Hidayatik, Nanik, Muhammad Agil, Entang Iskandar, Dyah Perwitasari-farajallah, Aswin Rafif Khairullah, Suryo Saputro, and Valen Sakti Maulana. "Behavior of female Tarsius spectrumgurskyae at the primate research center breeding facility." Open Veterinary Journal 15 (2025), 2059-2065. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i5.22 MLA (The Modern Language Association) Style Hidayatik, Nanik, Muhammad Agil, Entang Iskandar, Dyah Perwitasari-farajallah, Aswin Rafif Khairullah, Suryo Saputro, and Valen Sakti Maulana. "Behavior of female Tarsius spectrumgurskyae at the primate research center breeding facility." Open Veterinary Journal 15.5 (2025), 2059-2065. Print. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i5.22 APA (American Psychological Association) Style Hidayatik, N., Agil, . M., Iskandar, . E., Perwitasari-farajallah, . D., Khairullah, . A. R., Saputro, . S. & Maulana, . V. S. (2025) Behavior of female Tarsius spectrumgurskyae at the primate research center breeding facility. Open Veterinary Journal, 15 (5), 2059-2065. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i5.22 |