| Case Report | ||

Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(4): 1858-1863 Open Veterinary Journal, (2025), Vol. 15(4): 1858-1863 Case Report The first reported case of entropion and surgical correction in a snow leopard cub (Panthera uncia)Joy Dey, Pranita Gupta* and Basavaraj S. HoleyachiPadmaja Naidu Himalayan Zoological Park, Darjeeling, West Bengal *Corresponding Author: Pranita Gupta, Padmaja Naidu Himalayan Zoological Park, Darjeeling, West Bengal, India. Email: pnhzp [at] yahoo.com Submitted: 26/07/2024 Accepted: 17/03/2025 Published: 30/04/2025 © 2025 Open Veterinary Journal

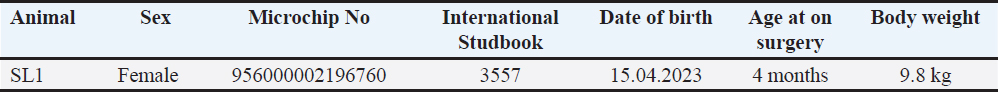

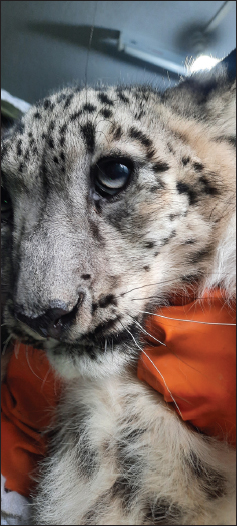

AbstractBackground: A 1-month-old female snow leopard cub at Padmaja Naidu Himalayan Zoological Park exhibited excessive tear production (lachrymation). Examination diagnosed primary entropion, a condition in which the eyelid margin folds inward due to developmental abnormalities, thereby resulting in corneal irritation and damage. Case Description: Initial conservative management with eyelid hair trimming and topical lubrication was attempted because the cub was young. However, persistent symptoms required surgical intervention using the modified Hotz-Celsus technique. This procedure successfully corrected the entropion without complications, as confirmed by thorough postoperative monitoring. Conclusion: This report is the first documented case of entropion in a snow leopard cub, demonstrating successful surgical resolution. This case provides significant insights into the diagnosis and treatment of ophthalmic conditions in this species, highlighting the importance of early intervention and precise surgical techniques in wildlife conservation. Keywords: Entropion, Snow leopard, Panthera uncia, Corneal ulceration. IntroductionSnow leopards (Panthera uncia) inhabit mountainous rangelands at elevations of 3,000 to over 5,000 meters in the Himalayas and Tibetan Plateau, although they can be found as low as 500 m in the Altai (Snow Leopard Network, 2014). These big cats are distinctly adapted to Asia’s cold and rugged mountains and are renowned for their ability to blend seamlessly with their surroundings. Snow Leopards range across 12 Central and South Asian countries: China, Bhutan, Nepal, India, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan, Russia, and Mongolia. According to the IUCN Red List, the snow leopard is classified as “Vulnerable,” with a global population estimated at more than 2,500 but fewer than 10,000 mature individuals and a projected decline of at least 10% over 22.62 years (three generations) (McCarthy et al., 2017). The Snow Leopard Population Assessment in India reported 718 Snow leopards in India (MoEFCC, 2024). Snow leopards face several significant threats, including habitat loss (Khan et al., 2021), a decline in their natural prey base (Lovari et al., 2009), retaliatory killings resulting from livestock predation (Jackson et al., 2010), the impacts of climate change (Li et al., 2021), and poaching for the illegal trade of their fur, bones, and other body parts (Snow Leopard Network, 2014; Wingard et al., 2014; Zahler and Victurine, 2016; Aryal, 2017). Entropion is the inversion of all or part of the eyelid margin, such that the outer skin contacts the conjunctival or corneal surface. This condition causes the eyelids and eyelashes to turn inward against the eyeball, leading to continuous irritation, pain, and distress from friction (Swain, 1902). Symptoms include intolerance to light, excessive tearing, and general signs of conjunctivitis. Entropion can be lateral, medial, angular, or total and may affect the lower or upper lid, or both. It can be primary (congenital or developmental) or secondary (acquired) and is influenced by factors such as the lid fissure length, skull conformation, orbital anatomy, gender, and the extent of facial skin folds around the eyes. The inverted eyelid margin causes irritation, excessive tearing, mucopurulent discharge, conjunctival hyperemia, and blepharospasm, with chronic irritation leading to edema, neovascularization, granulation, pigmentation, and ulceration (Gelatt, 2013). While entropion is widely reported in certain dog breeds (Asti et al., 2019), it is rare in cats and is usually secondary to chronic conjunctivitis or keratitis. There are no reported cases of entropion in captive snow leopards. Other ocular anomalies in snow leopards, such as multiple ocular coloboma, bilateral anterior segment dysgenesis (Peters’ anomaly), and metastatic multifocal iris melanoma, have been documented (Gripenberg et al. 1985; Hamoudi et al., 2013; Wiesner and Fristche, 2019). Padmaja Naidu Himalayan Zoological Park (PNHZP), located in Darjeeling, West Bengal, India, at an elevation of 7000 feet (2,134 meters), is the largest high-altitude zoo in India. It specializes in the conservation breeding of rare and endangered species from the Eastern Himalayan region, such as the red panda and snow leopard. Since 1983, the PNHZP has been involved in the global captive breeding program for snow leopards, and it currently holds the largest captive population of these species. This report presents the first documented case of snow leopard entropion. Case DetailsA female Snow leopard (Panthera uncia) at the conservation breeding center of Padmaja Naidu Himalayan Zoological Park (PNHZP) gave birth to two cubs, one male and one female (SL1). Both cubs exhibited optimal growth; however, the female cub (SL1) showed signs of excessive lachrymation at one month of age (Fig. 1). Subsequent examination revealed primary entropion. The details of the snow leopard cub are provided in Table 1. The surgery was initially postponed to prevent the potential recurrence of entropion with age and to reduce stress, given the cub’s young age and ongoing growth. At 3 months of age, an alternative management approach was adopted, involving daily trimming of the palpebral cilia and daily application of a topical lubricant for 3 weeks to alleviate discomfort.

Figure 1. Lachrymation at 1 month of age.

Figure 2. Corneal ulceration. Table 1. Details of snow leopard cub.

Figure 3. Post-surgery.

Figure 4. Day 1 postoperatively. At 4 months of age, however, due to the onset of corneal ulceration (Fig. 2), a decision to perform surgical correction of the entropion was made. The cub was sedated with a combination of 25 mg Ketamine (2.5mg/kg body weight; Neon Laboratories, Mumbai, India) and 20 mg Xylazine (2mg/kg body weight; Brilliant Bio Pharma Pvt Ltd., Telangana, India) administered intramuscularly in the gluteus muscle. The surgical procedure chosen was the modified Hotz-Celsus technique (Diaz and Grundon, 2015). Local anesthesia was not used. To ensure adequate aseptic conditions, the fur on the lower eyelid was shaved and 10% w/v povidone-iodine was applied. An initial incision was made with a scalpel blade (2 mm) parallel to the eyelid margin, with care taken to protect the ocular surface. The incision was extended to cover the region affected by entropion, with an additional 2–3-mm margin on either side. Thumb pressure was applied at the point of entropion to roll out the eyelid until the meibomian gland orifices were visible. A curvilinear incision was then made ventral to the first to connect the ends of the initial incision. The tissue was removed from the most inverted section of the eyelid to prevent the recurrence of the inversion, ensuring that the orbicularis oculi muscle was not excised. The dermis and subcutaneous tissues were closed with continuous subcuticular sutures. The epidermis was closed with simple interrupted sutures to achieve proper eversion of the palpebra. Suturing was performed using Vicryl® 1/0 and 0 (Ethicon, Somerville, NJ, USA). Sedation was reversed with intravenous 0.2 mg of yojibine (Akorn, Lake Forest, IL, USA), and the cub recovered smoothly within 1 minute. Postoperatively the cub was administered a daily intramuscular dose of 562.5 mg Ceftriaxone and Tazobactam (Excellar Health Care Pvt., Ltd, Thane, India) for 7 days. Meloxicam (30 mg; Neovet, Ahmedabad, India) was also given orally for 5 days. A topical application of 2% muquirocin ointment (Alkem Laboratories, Thane, India) was applied over the incision site for 14 days to aid healing. Postoperatively (Figs. 3 and 4), cicatrix formation was observed after 1 week. Complete healing with absorption of the suture material occurred within 2 weeks (Fig. 5). There was no recurrence of entropion or excessive tear production (lachrymation) at 1 month (Fig. 6) and eleven months of age (Fig. 7), confirming the surgical success.

Figure 5. Day 14 postoperatively.

Figure 6. Day 30 postoperatively

Figure 7. Day 120 postoperatively. DiscussionThis case report describes the first reported instance of entropion in a snow leopard cub and its successful surgical correction. It contributes significantly to veterinary ophthalmology, particularly in managing ocular conditions in rare species. Temporary tarsorrhaphy was not employed to avoid stress to the cub; instead, a definitive surgical intervention was chosen. Early surgical management prevented further development of corneal ulceration, which is a potential complication of entropion. Entropion is a condition characterized by the inward turning of the eyelid, which causes the eyelashes to come into contact with the cornea of the eye. This can lead to irritation, pain, and, if left untreated, corneal damage that may result in blindness (Gelatt, 2013). It is relatively common in canines, but not in felines. A survey conducted by Williams and Kim (2009) identified 41 published articles on canine entropion. In contrast, only 14 articles addressed feline entropion, with only one exclusively focusing on eyelid in-turning in cats (Weiss, 1980). The study by Williams and Kim (2009), which examined 50 affected cats, indicated that entropion in cats might be caused in young animals by continued blepharospasm related to irritative causes, such as conjunctivitis or corneal ulceration, or in older animals by lid laxity or globe enophthalmos. While entropion is common in domestic animals, it is rarely observed in wild felids. The limited documentation of such cases in large wild cats, like the snow leopard, may reflect underdiagnosis or underreporting due to the challenges of monitoring and managing wildlife health. However, other ocular conditions have been recorded in wild felids. Multiple ocular coloboma have been documented in Snow leopards (Panthera uncia) (Gripenberg et al., 1985; Georoff and Marlar, 2023). Bilateral anterior segment dysgenesis (ASD), specifically Peters’ anomaly, has been observed in two Snow leopards (Panthera uncia) (Hamoudi et al., 2012). Eyelid agenesis was reported in a captive cheetah cub (Acinonyx jubatus) (Boucher et al., 2016). Additionally, bilateral eyelid agenesis with multiple ocular anomalies, such as interpapillary fundic coloboma, persistent pupillary membranes, and an atypical iris coloboma, was described in a Texas cougar (Puma concolor) (Cutler, 2002). An investigation by Gripenberg et al. (1985) did not confirm whether coloboma in snow leopards were genetically related but ruled out a chromosomal abnormality. Georoff and Marlar (2023) retrospectively studied medical records to identify snow leopards with eyelid coloboma diagnosed between January 1, 2000, and December 31, 2020. Eyelid coloboma was diagnosed in 49 animals (14.6%), with cases originating from 20 zoological institutions in the US. A high percentage (73.5%) had an affected sibling, parent, or grandparent, suggesting a heritable component. This case of entropion in a snow leopard cub is particularly notable because it appears to be primary, likely resulting from congenital or developmental anomalies. This condition is distinct from domestic cats, which typically develop entropion secondary to chronic conjunctivitis or other irritative causes (Williams et al., 2009). Notably, no inbreeding was recorded in this individual, further emphasizing the uniqueness of this case. The sire of this cub (SL1) was approximately 5 years old at the time of its birth, and the dam was approximately 10 years and 10 months old. The affected animal and both parents had an inbreeding coefficient of 0, and the parents together had previously produced one normal litter. This distinction is critical for understanding the etiology of entropion in snow leopards and for guiding the appropriate management of entropion in felines. White et al. (2011) evaluated the success rate of various surgical techniques for managing lower eyelid entropion in cats. Their study, which reviewed cases from 124 cats, found that a combined Hotz-Celsus and lateral canthal closure was the most effective technique. Prophylactic lateral canthal closure in the unaffected eye was also recommended. Most cases of feline entropion have been reported in smaller domestic cats. The challenges of monitoring wild felines and the potential rarity of the condition likely contribute to the lack of documented cases. In this case, temporary eye tacking sutures, which were used as a temporary measure to prevent corneal ulceration (until a permanent procedure can be performed at an older age), were not chosen to reduce undue stress on the cub, and definitive entropion surgery was chosen. This case report is paramount for wildlife veterinarians because it infers that entropion cases might occur in snow leopards and can be surgically corrected without complications at a young age. Delaying surgical correction may lead to corneal ulceration and ultimately blindness. Direct surgical correction of entropion is an effective solution, as opposed to temporary measures such as eye-tacking sutures. The lack of literature on entropion in large felids, like snow leopards, suggests that this condition may be underdiagnosed or underreported. This case highlights the importance of vigilant health monitoring and prompt intervention in captive wildlife populations. Future research should document similar cases across different zoological institutions to better understand the prevalence and best management practices for entropion and other ophthalmic conditions in wild felids. This would aid in conservation efforts in zoological parks and sanctuaries worldwide. AcknowledgmentsThe Authors would like to thank Shri Debal Ray IFS, Principal Chief Conservator of Forest (PCCF) and the Chief Wildlife Warden (CWLW), West Bengal, and Shri Saurabh Chaudhuri IFS, Member Secretary of the West Bengal Zoo Authority (WBZA), for supporting the snow leopard’s conservation breeding program. We would also like to thank the Padmaja Naidu Himalayan Zoological Park staff. Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest. Author’s contributionsDr. Joy Dey: Assistant director and Veterinary officer. Responsible for treatment and surgical procedures. Contributed to the clinical aspects of the study. Pranita Gupta: Zoo Biologist. Managed documentation, manuscript writing, and editing. Key role in drafting and refining the manuscript. Dr. Basavaraj S. Holeyachi: Director. Overall supervision and guidance throughout the project. Ensured the integrity and accuracy of the work. FundingNo specific grant was received. Data AvailabilityAll data supporting the findings of this study are available in the manuscript. ReferencesAryal, A. 2017. Poaching: Is the snow leopard tally underestimated? Nature. 550(7677), 457. Asti, M., Nardi, S. and Barsotti, G. 2012. Surgical management of bilateral, upper, and lower eyelid entropion in 27 Shar Pei dogs, using the Stades forced granulation procedure of the upper eyelid only. N. Z. Vet. J. 68(2), 112–118. Boucher, C.J., Venter, I.J., Janse van Rensburg, D. and Sweers, L. 2016. Eyelid agenesis and multiple ocular defects in a captive cheetah cub (Acinonyx jubatus). Vet. Rec. Case Rep. 4(1), e000301. https://doi.org/10.1136/vetreccr-2016-000301 Cutler, T.J. 2002. Bilateral eyelid agenesis repair in a captive Texas cougar. Vet. Ophthalmol. 5(3), 143–148. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1463-5224.2002.00237.x Diaz, J. and Grundon, R. 2015. Diagnosis and treatment of entropion in cats. Vet. Times 45(28), 9–11. Gelatt, K. N. 2013. Canine eyelids: diseases and surgery. In Essentials of veterinary ophthalmology, Eds., K. N. Gelatt, Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, pp: 170–192. Georoff, T.A. and Marlar, A.B. 2023. Retrospective review of eyelid coloboma in snow leopards (Panthera uncia) housed under managed care in North America: 49 cases (2000–2020). J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 261(12), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.2460/javma.23.04.0203 Gripenberg, U., Blomqvist, L., Pamilo, P., Soderlund, V., Tarkkanen, A., Wahlberg, C., Varvio-Aho, S.L. and Virtaranta-Knowles, K. 1985. Multiple ocular coloboma (MOC) in snow leopards (Panthera uncia): Clinical report, pedigree analysis, chromosome investigations, and serum protein studies. Hereditas 103(2), 221–229. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1601-5223.1985.tb00505.x Hamoudi, H., Rudnick, J.C., Prause, J.U., Tauscher, K., Breithaupt, A., Teifke, J.P. and Heegaard, S. 2013. Anterior segment dysgenesis (Peters’ anomaly) in two snow leopard (Panthera uncia) cubs. Vet. Ophthalmol. 16(6), 130–134. Jackson, R.M., Mishra, C., McCarthy, T.M. and Ale, S.B. 2010. Snow leopards: conflict and conservation. In The biology and conservation of wild felids, Eds., D. Macdonald and A. Loveridge, Oxford: University Press, pp: 417–430. Khan, T.U., Mannan, A., Hacker, C.E., Ahmad, S., Siddique, M.A., Khan, B.U., Din, E.U., Chen, M., Zhang, C., Nizami, M. and Luan, X. 2021. Use of GIS and remote sensing data to understand the impacts of land use/land cover changes (LULCC) on snow leopard (Panthera uncia) habitat in Pakistan. Sustainability 13(7), 3590. Li, J., Xue, Y., Hacker, C.E., Zhang, Y., Li, Y., Cong, W., Jin, L., Li, G., Wu, B., Li, D. and Zhang, Y. 2021. Projected impacts of climate change on snow leopard habitat in Qinghai Province, China. Ecol. Evol. 11(23), 17202–17218. Lovari, S., Boesi, R., Minder, I., Mucci, N., Randi, E., Dematteis, A. and Ale, S.B. 2009. Restoring a keystone predator may endanger a prey species in a human-altered ecosystem: The return of the snow leopard to Sagarmatha National Park. Anim. Conserv. 12(6), 559–570. McCarthy, T., Mallon, D., Jackson, R., Zahler, P. and McCarthy, K. 2017. Panthera uncia. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2017: e.T22732A50664030. Available via https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-2.RLTS.T22732A50664030.en (Accessed 30 May, 2024). MoEFCC 2024. Status of Snow Leopard in India (SPAI). Ministry of Environment and Forests. Government of West Bengal. Available via https://wii.gov.in/images/images/documents/publications/SPAI_report_2024.pdf Snow Leopard Network 2014. Snow Leopard Survival Strategy. Version 2014.1. Snow Leopard Network. Available via www.snowleopardnetwork.org. Swain, S.H. 1902. Ectropion and entropion. J. Comp. Med. Vet. Arch. 23(8), 501–503. Weiss, C.W. 1980. Feline entropion. Feline Pract. 10, 38–45. White, J.S., Grundon, R.A., Hardman, C., O’Reilly, A. and Stanley, R.G. 2011. Surgical management and outcome of lower eyelid entropion in 124 cats. Vet. Ophthalmol. 15(4), 231–235. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1463-5224.2011.00974.x Wiesner, M. and Fritsche, J. 2019. Three different ocular diseases in captive snow leopards (Uncia uncia) and cheetahs (Acinonyx jubatus). Wien. Tierärztl. Monatsschrift. 106(1/2), 23–30. Williams, D.L. and Kim, J.Y. 2009. Feline entropion: a case series of 50 affected animals (2003-2008). Vet. Ophthalmol. 12(4), 221–226; doi:10.1111/j.1463-5224.2009.00705.x Wingard, J., Zahler, P., Victurine, R., Bayasgalan, O. and Buuveibaatar, B. 2014. Guidelines for addressing the impact of linear infrastructure on large migratory mammals in Central Asia. Convention on Migratory Species Technical Report. Bonn, Germany. Zahler, P. and Victurine, R. 2016. Linear infrastructure and snow leopard conservation. In Snow Leopards (Biodiversity of the World: Conservation from Genes to Landscapes), Eds., T. McCarthy and D. Mallon, Cambridge, MA: Academic Press, pp: 123–126. | ||

| How to Cite this Article |

| Pubmed Style Dey J, Gupta P, Holeyachi BS. The first reported case of entropion and surgical correction in a snow leopard cub (Panthera uncia). Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(4): 1858-1863. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i4.38 Web Style Dey J, Gupta P, Holeyachi BS. The first reported case of entropion and surgical correction in a snow leopard cub (Panthera uncia). https://www.openveterinaryjournal.com/?mno=210116 [Access: January 25, 2026]. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i4.38 AMA (American Medical Association) Style Dey J, Gupta P, Holeyachi BS. The first reported case of entropion and surgical correction in a snow leopard cub (Panthera uncia). Open Vet. J.. 2025; 15(4): 1858-1863. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i4.38 Vancouver/ICMJE Style Dey J, Gupta P, Holeyachi BS. The first reported case of entropion and surgical correction in a snow leopard cub (Panthera uncia). Open Vet. J.. (2025), [cited January 25, 2026]; 15(4): 1858-1863. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i4.38 Harvard Style Dey, J., Gupta, . P. & Holeyachi, . B. S. (2025) The first reported case of entropion and surgical correction in a snow leopard cub (Panthera uncia). Open Vet. J., 15 (4), 1858-1863. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i4.38 Turabian Style Dey, Joy, Pranita Gupta, and Basavaraj S. Holeyachi. 2025. The first reported case of entropion and surgical correction in a snow leopard cub (Panthera uncia). Open Veterinary Journal, 15 (4), 1858-1863. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i4.38 Chicago Style Dey, Joy, Pranita Gupta, and Basavaraj S. Holeyachi. "The first reported case of entropion and surgical correction in a snow leopard cub (Panthera uncia)." Open Veterinary Journal 15 (2025), 1858-1863. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i4.38 MLA (The Modern Language Association) Style Dey, Joy, Pranita Gupta, and Basavaraj S. Holeyachi. "The first reported case of entropion and surgical correction in a snow leopard cub (Panthera uncia)." Open Veterinary Journal 15.4 (2025), 1858-1863. Print. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i4.38 APA (American Psychological Association) Style Dey, J., Gupta, . P. & Holeyachi, . B. S. (2025) The first reported case of entropion and surgical correction in a snow leopard cub (Panthera uncia). Open Veterinary Journal, 15 (4), 1858-1863. doi:10.5455/OVJ.2025.v15.i4.38 |